August 3, 2021

The global plastic pollution crisis is approaching an irreversible ‘tipping point’

BY: Emily Nuñez

If you follow climate news, you may have heard the term “tipping point.” It refers to a temperature threshold that, once crossed, triggers a chain of negative effects that can’t be undone. One worrying example has to do with ice sheets: If we don’t significantly curb greenhouse gas emissions and limit global warming, there will come a time when we’re unable to stop Arctic and Antarctic ice sheets from melting, unleashing a dangerous rise in sea levels that could submerge entire cities and small island nations.

According to a new paper published in the journal Science, plastic pollution is approaching a similar point – and our window for action is quickly closing. Up to 23 million metric tons of plastic end up in rivers, lakes, and oceans each year, and that amount could potentially double by 2025 if nothing is done to stop it. Once plastic enters the ocean, it can linger for decades or even centuries. Larger plastics can be deadly to marine animals that ingest or become entangled in them, and accumulations of smaller microplastics pose a global – and practically invisible – threat to ecosystems.

Because this material is so pervasive and so difficult to remove from water and soil, plastic pollution fits the description of a “poorly reversible pollutant,” researchers wrote. And if the deluge of plastic pollution exceeds our ability to clean it up, it could mean more carbon in our atmosphere and less biodiversity in our oceans.

“The cost of ignoring the accumulation of persistent plastic pollution in the environment could be enormous,” Matthew MacLeod, the study’s lead author and a professor at Stockholm University, said in a university-issued news release. “The rational thing to do is to act as quickly as we can to reduce emissions of plastic to the environment.”

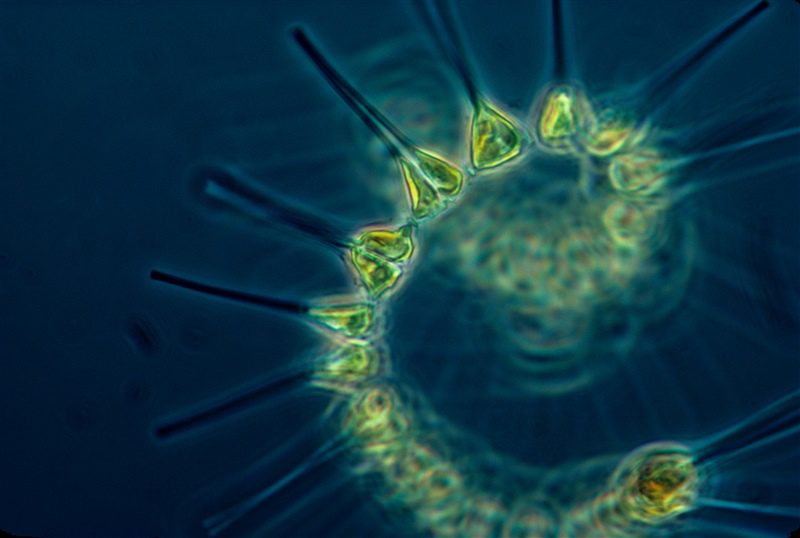

Researchers outlined the ways in which plastic could irreversibly alter the environment, including its potential impact on global carbon cycles. Higher concentrations of plastic could affect the food sources or access to sunlight of marine organisms like cyanobacteria and phytoplankton, which, despite being tiny, soak up significant amounts of carbon. If their ability to sequester carbon is limited, that carbon would instead linger in the atmosphere and contribute to global warming.

Microplastics also attract and host communities of microorganisms, which form a layer called a “biofilm.” These biofilms on plastic are known to hamper the delivery of important nutrients, like nitrogen and phosphorus, to deep sea environments.

“Meanwhile, the increasing loads of carbon in nonbuoyant plastic will sink, with one estimate indicating that the amount of plastic carbon being buried in seabed sediments could exceed that of natural organic carbon by 2050 in hot-spot regions,” the authors wrote, citing another recent study. In other words, these sinking plastics may also affect the health of seabed sediments and the ocean’s natural ability to sequester carbon.

Plastic pollution tends to be viewed as an isolated issue – separate from overfishing, climate change, and other problems that plague the ocean – but MacLeod and co-authors emphasized their interconnectedness. Marine species that have already been forced to adapt to warmer waters or a dwindling supply of nutrients may struggle to adapt to the additional threat of plastic pollution. When these “stressors” start to stack up, it could contribute to a loss of biodiversity.

While the clock is ticking to prevent this tipping point from coming true, it’s not too late. Researchers say the most logical course of action is to focus on regulations that reduce plastic emissions “as rapidly and comprehensively as possible.” Mine B. Tekman, a co-author of the paper, said cleanup technologies and recycling are not enough to prevent catastrophe.

“As consumers, we believe that when we properly separate our plastic trash, all of it will magically be recycled. Technologically, recycling of plastic has many limitations, and countries that have good infrastructures have been exporting their plastic waste to countries with worse facilities,” Tekman said. “Reducing emissions requires drastic actions, like capping the production of virgin plastic to increase the value of recycled plastic, and banning export of plastic waste unless it is to a country with better recycling.”

Only 9% of all the plastic waste ever produced has been recycled and, technically speaking, much of that waste was “downcycled” into lower-quality materials that can never be recycled again. There is little market for lower-value plastics (which includes everything except for #1 and #2 plastics), and there is little incentive for manufacturers to use recycled plastics because virgin plastics are often cheaper.

Oceana recognizes that reactive measures, like recycling, are no match for proactive measures that stop plastic pollution at the source. In practice, this means enacting policies that make it easier for consumers to choose plastic-free and ocean-friendly options.

Following campaigning by Oceana, the Chilean government passed a law that prohibits restaurants from serving throwaway plastic tableware. The law stipulates that any disposable tableware provided by delivery and take-out facilities must be made from materials other than plastic or made of certified plastic. In addition, stores must actively display, sell, and receive refillable bottles.

Similar progress was made in Peru, which passed a law to phase out single-use plastic bags, and in Belize, which passed a law to remove single-use plastic and polystyrene products from the food sector. And across the U.S., various local and state governments have passed laws that curb plastic pollution by limiting the sale and distribution of single-use plastics, or by banning acts that indirectly harm animals and ecosystems, like intentional balloon releases.

A world without wasteful single-use plastics is not only possible – it’s also necessary. To learn more about Oceana’s global plastics campaign, click here.