September 25, 2019

Climate change and oceans: What you need to know from the United Nations’ new report

BY: Emily Nuñez

From the global climate strikes to MSNBC’s presidential candidate climate forum to teen activist Greta Thunberg’s fiery speech at the UN Climate Action Summit, climate change has been a recurring topic in the news cycle this past week.

Today, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change prolonged that momentum by releasing a groundbreaking report that “provides the first-ever global scientific consensus on the severe consequences of climate change for the ocean,” according to the agency.

More than 100 scientists from 36 countries contributed to the document, which also highlights the significant ways climate change affects the cryosphere – including ice sheets, glaciers and other bodies of ice and snow.

The findings are bleak, but scientists stress that it isn’t too late to change course and prevent many of the worst projected outcomes. Outlined below are a few key findings from the 1,170-page report, titled Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, as well as a few ways we can tackle the climate crisis head-on.

1. The ocean is getting hotter, faster.

The pace of ocean warming has more than doubled since 1993. That’s because oceans have absorbed 90% of the extra heat generated by human activity.

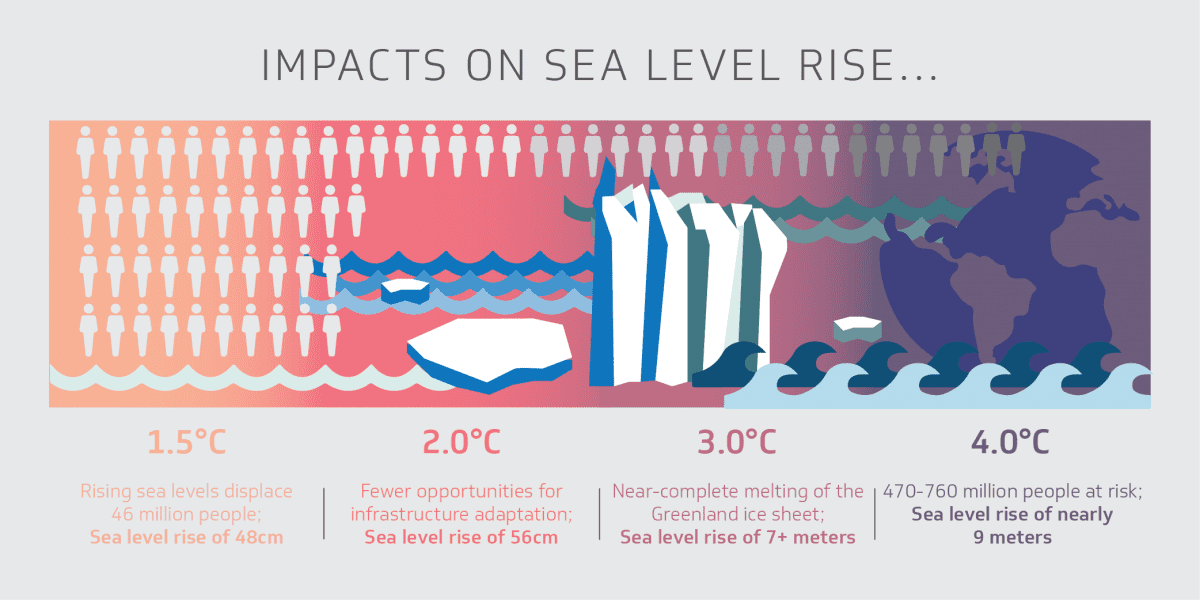

2. Sea levels are rising at an accelerated rate.

This is mostly due to ice sheets melting, especially in Greenland and Antarctica. To a lesser extent, sea level rise is caused by melting glaciers and thermal expansion, which occurs when warmer temperatures cause water to expand. The oceans could rise by 3 feet over the next 80 years if action isn’t taken. And if trends continue, sea level rise could surpass 17 feet by 2300.

3. Warmer waters are causing more intense storms.

Higher sea levels are also fueling larger storm surges, leading to more extreme floods. Current projections indicate that extreme floods could become common along coasts by 2100.

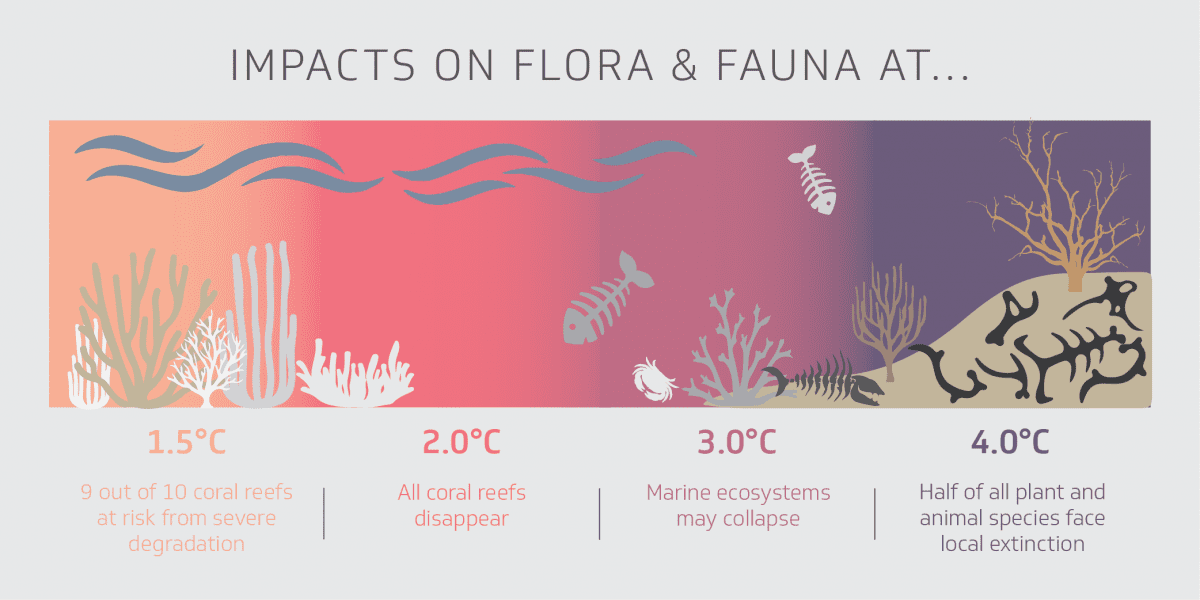

4. Coral reefs are projected to decline by up to 90% if global warming is limited to a 1.5°C rise.

Corals are especially vulnerable to heat waves, which can cause mass bleaching events, severely diminishing their ability to survive and thrive.

5. The ocean is becoming more acidic.

More carbon dioxide in the air means more carbon dioxide in the ocean, and these changes to the ocean’s chemistry have real and lasting consequences for marine animals, including decreased growth and reproduction rates, a higher susceptibility to disease and behavioral changes. “Continued carbon uptake by the ocean by 2100 is virtually certain to exacerbate ocean acidification,” the report states.

6. Fisheries are being disrupted.

In some parts of the world, fish catch is already declining. Many commercially important species are seeking refuge in colder waters, which could threaten the livelihoods of millions of people. If current trends continue, small-scale coastal fisheries are expected to see a 20% decline in fish catch potential.

How is Oceana addressing these problems?

“Ocean-based interventions could close up to 21 percent of the emissions gap by 2050,” according to a separate report, released Monday by the High Level Panel for A Sustainable Ocean Economy – a group composed of 14 prime ministers and presidents.

Oceana already works on several of the recommended interventions, including:

1. Promoting sustainable seafood as a healthy, low-carbon source of protein.

Advocating a diet rich in “greenhouse gas-friendly seafood options,” which tend to have a lower carbon footprint than land-based meats like beef and pork, makes an impact. However, this only works if seafood can be caught and brought to market sustainably, the report’s authors write.

As Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg and Palauan President Tommy Remengesau Jr. explained in an article for CNN: “… Developing low-carbon sources of protein from the ocean – like seafood, seaweeds and kelp – can provide a healthy and sustainable diet for future populations while easing emissions from land-based food production.”

2. Pushing for policies that would restore global fish stocks to abundance.

The connection between climate change and fisheries management might not always be obvious, but championing smart, science-based policies around the globe is an important step in the fight to mitigate climate change and ensure food security.

One of the biggest policy changes of all would be implementing the recommendations outlined in the Paris Agreement. If global leaders follow the Agreement, it would ensure the protection of up to 3.3 million metric tons of ocean catch – more than the average annual fish catch of Norway, one of the world’s top fishing countries – and increase fisher revenue by $4.6 billion.

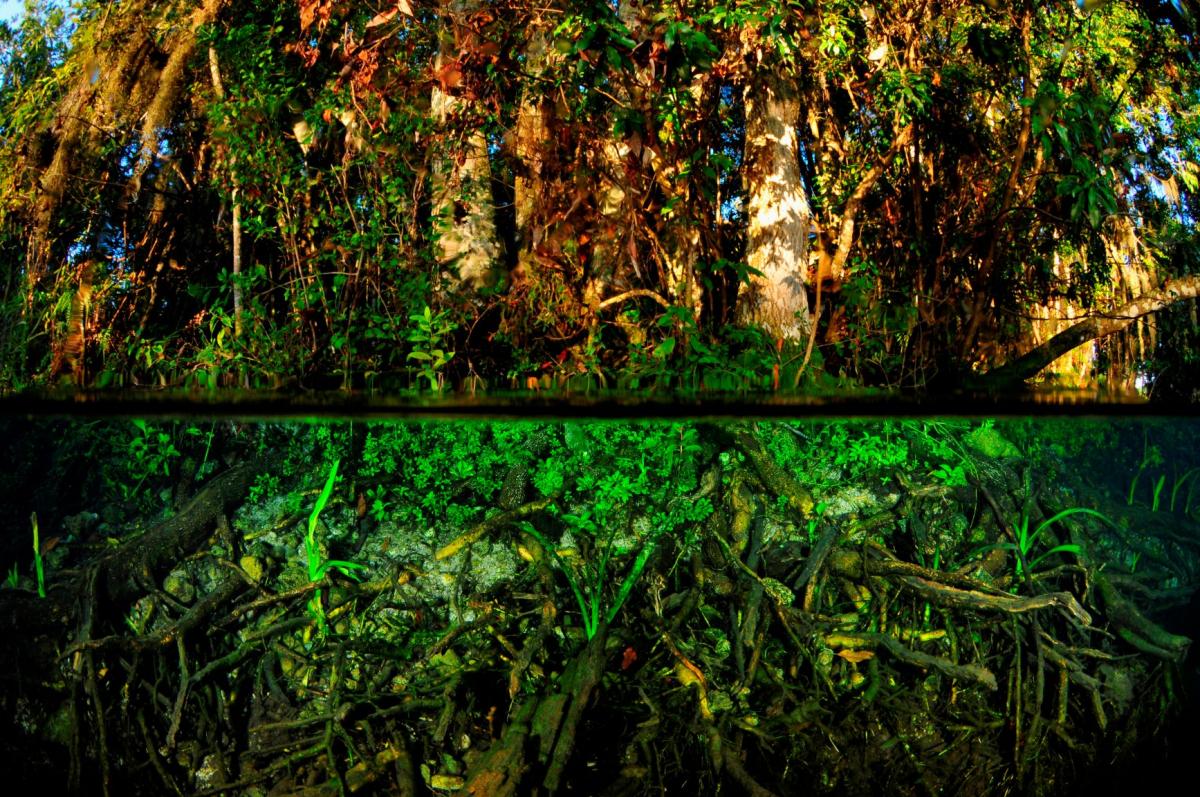

3. Protecting important aquatic plants and trees that sequester carbon.

Oceana also campaigns to preserve carbon-sequestering vegetation, including kelp in Chile and mangroves and seagrasses in the Philippines. Mangroves and seagrasses in particular are able to absorb and store carbon that may have built up over hundreds or thousands of years, but when they’re destroyed, all that carbon gets released back into the atmosphere in mere decades.

Unfortunately, 20 to 50% of the world’s “blue carbon ecosystems” have already been converted or degraded, according to the report. Conserving, restoring and expanding these ecosystems are all ways of promoting natural buffers against climate change.

Findings from the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate may be grim, but experts make it clear that it’s not time to give up hope. With bold, decisive and immediate action our planet – and our oceans – can be spared from the catastrophic consequences of climate change.

“We need to, right now, work to make our seas as abundant and resilient as possible,” Oceana CEO Andrew Sharpless said.

“With the support and guidance of Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Vibrant Oceans Initiative and other funders, Oceana is winning victories that help end overfishing, rebuild fisheries and preserve habitat though the establishment of science-based management and protected areas in some of the largest fishing countries on the planet.”