December 20, 2016

Some Kelp Forests Show Surprising Resistance to Climate Change – But It’s Not All Good News

BY: Allison Guy

On a recent Tuesday, Michael Graham was driving to the Monterey Bay Aquarium to deliver baggies of kelp in sterilized seawater. Graham is the director of research and development at the Moss Landing Marine Lab’s Center for Aquaculture and the editor of the world’s top publication on algae, so the assumption might be that those bagged kelps were scientific samples. But the only sampling that day was of the culinary kind — the kelp was destined for the aquarium’s salad bar.

Graham runs a small edible seaweed business out of his lab. There, four types of native kelp grow in white, seawater-fed tanks beneath the year-round California sun. There’s crunchy ogo, emerald green sea lettuce and red dulse, which became famous in certain corners of the web as ‘bacon seaweed.’

“It doesn’t taste like bacon,” Graham said, but it does boast some similarities. “When you fry it, the salt comes to the surface, so you get that super-salty bite right off the bat. Vegan restaurants love it.”

Graham’s enthusiasm for kelp aquaculture is more than a hobby. He sees this order of over a hundred species as potential winners in the climate change lottery. That’s because big swaths of kelp forests around the globe are showing surprising resilience as hotter, more acidic ocean conditions knock out seagrasses, coral reefs and other foundational marine species.

A five-star kelp review

Kelp is a widespread, weedy group — it’s found on the coastline of every continent except Antarctica — but that doesn’t mean it’s not picky. These giant varieties of brown algae rely on clear, nutrient-rich water to support their speedy growth habits, and thrive in temperatures between 5 and 20 Celsius (42 to 72 Fahrenheit).

Climate change makes water hotter and weakens the currents that drive nutrients up from the ocean’s depths. This should mean that kelp, like tropical coral, would be highly sensitive to warming seas. But as a handful of new reports have shown, kelp hates to play to type.

An analysis released in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences last November found that of the major kelp ecosystems for which there are data, 38 percent were declining and 27 percent showed small levels of growth. A further 35 percent showed no change. The modest global decline, the authors noted, paled in comparison to massive variations on local and regional scales.

“We found that kelps are remaining resilient to disturbances in many areas of the world,” said lead author Kira Krumhansl, a researcher at Simon Fraser University. “This is a good news story relative to many other species.”

“Our findings show that there’s a lot we can do locally to manage the health of kelp ecosystems,” she added. These include reducing pollution and ending the overfishing or overhunting of predators that eat herbivores like sea urchins, which can mow down kelp forests if left unchecked.

“But,” Krumhansl said, “there are still a lot of pressures facing kelp ecosystems, and climate change is one of the main ones that threatens the ability of kelps to recover from decline.”

The startling differences scientists are seeing among kelp forests — even those subject to similar extreme temperatures — are exemplified by Southern California, British Columbia and Australia. Giant kelp in much of North America is flourishing, despite a years-long marine heat wave. But across the Pacific, hot water is wiping out ancient kelp forests practically overnight.

Green machine

In 2013, a massive ‘blob’ of hot water formed in the northern Pacific Ocean. The blob crept towards land, and by 2014, it had parked itself along the West Coast from Alaska to Baja California — and it’s more or less stayed put since then.

The blob should be cooking the West Coast’s giant kelp. But as satellite data from a study released last Tuesday in Nature Communications showed, while kelp in Southern California fluctuated dramatically from 1984 to 2015, these shifts showed little response to temperature.

“This result is quite surprising given giant kelp’s reported sensitivity to such conditions,” the authors wrote, “and stands in contrast to reports from other kelp systems showing sharp declines in response to warming conditions.”

Southern California has “persistent, beautiful kelp,” Graham said. He explained that the region’s green giants “are far more resilient and variable” than we’ve given them credit for.

This scene is repeated in British Columbia. According to Krumhansl, kelp there is “relatively stable or even increasing” in large part thanks to rebounding populations of urchin-eating sea otters, which were once ruthlessly hunted for their fur. The Heiltsuk First Nation in Bella Bella is partnering with scientists to understand how to sustainably harvest their rebounding kelp.

Kelp makes top-notch fertilizer for vineyards, Krumhansl explained, not to mention being highly nutritious for humans, livestock and farmed fish. Adding to that is its beauty. On a clear day in Bella Bella, Krumhansl said, “you can see fish swimming through the kelp fronds and sunlight filtering down through the water. Everything is swaying gently because giant kelp forests are really calm. There’s always a lot to discover.”

Gone in a blink

Australia is a half world away from British Columbia, but it might as well be in a different universe when it comes to kelp.

Along with Tasmania’s once-extensive kelp forests, the region is home to the ‘Great Southern Reef’ — an 8,000 kilometer (5,000 mile) stretch of kelp and rocky reefs along Australia’s southern edge. This verdant border brings in an estimated $10 billion each year to Australia’s economy, and provides the fuel for lobster and abalone, the country’s two most valuable fisheries. But despite its value, it’s disappearing before our eyes.

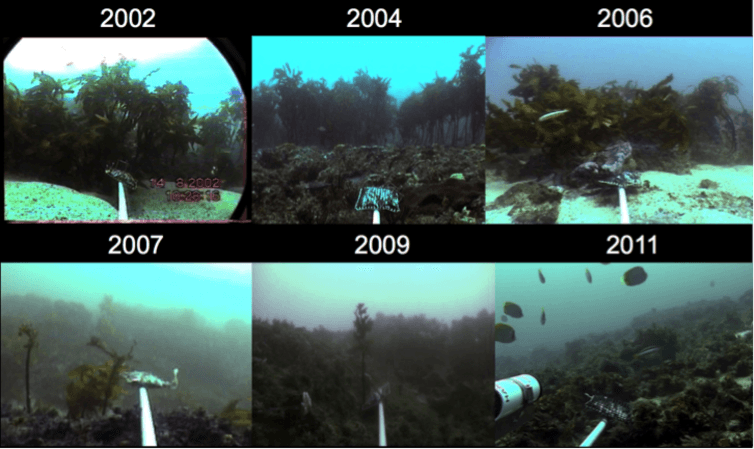

In 2011, a severe marine heat wave — Australia’s own version of the ‘blob’ — wiped out kelp forests along 100 kilometers (62 miles) of coastline, leaving a ragged, lawn-like turf where stately columns of greenery once grew.

A paper published last October suggested that these losses might represent the new normal for Australia. As warm-water herbivores like urchins and rabbitfish extend their range southwards, their grazing shaves regenerating kelp down to nubs. This process, called ‘tropicalization,’ prevents kelp regrowth even once a heat wave has passed.

Thomas Wernberg, a researcher at the University of Western Australia, said that Australia and Tasmania’s kelp forests may have been particularly hard-hit because they already live near the upper limit of their heat tolerance. This region is also one of the fastest warming spots on earth, with a big intensification of a major current that carries warm, nutrient-poor water and transports new kelp herbivores.

As for marine heat waves like the one in 2011, Wernberg explained that they are predicted to worsen. “It is hard to see how this could be turned around in the foreseeable future,” he said. “Giant kelp is likely to go functionally extinct in Australia within the next 50 to 100 years, if not sooner.”

A frond in need

Despite the apocalyptic scenario playing out in Australia, should we at least be reassured that kelp is going gangbusters elsewhere? For Wernberg, “it provides little consolation. By comparison what good is it that the pine forests in Scandinavia are expanding if the Amazon is contracting?”

Even Graham, who spoke about kelp’s future with more enthusiasm, explained that the world’s underwater forests have their upper limits. “You can’t take it from 55 degrees Fahrenheit to 80 degrees Fahrenheit and just expect it to do fine,” Graham said. “You can’t turn kelp into coral.”