August 12, 2016

In Photos: After a Gargantuan Recovery, Can Gray Whales Rule a Changing World?

BY: Allison Guy

The clan of gray whales that plies the ocean from the Bering Sea to the Baja Peninsula is one of conservation’s great success stories. Once given up for dead, the Eastern North Pacific population rebounded from less than 2,000 in the early 20th century to over 20,000 today. But with their Arctic feeding grounds changing swiftly, can these gray giants take the heat?

Gray whales can reach 15 meters (50 feet) and weigh 40 tons. They’re unique among baleen whales for their odd approach to mealtimes: Instead of filtering plankton and fish from the water, they scoot along the seafloor pitched to one side, vacuuming up clouds of sediment to sieve out worms, crustaceans and other small animals.

.

These marine behemoths boast one of the most grueling migrations of any mammal on earth. From their summer feeding grounds in the Arctic, they travel tens of thousands of kilometers south to calving lagoons in Baja California, Mexico. In 2015, one champion female named Vavara travelled 22,511 kilometers (13,988 miles) in 172 days, the longest mammal migration ever recorded.

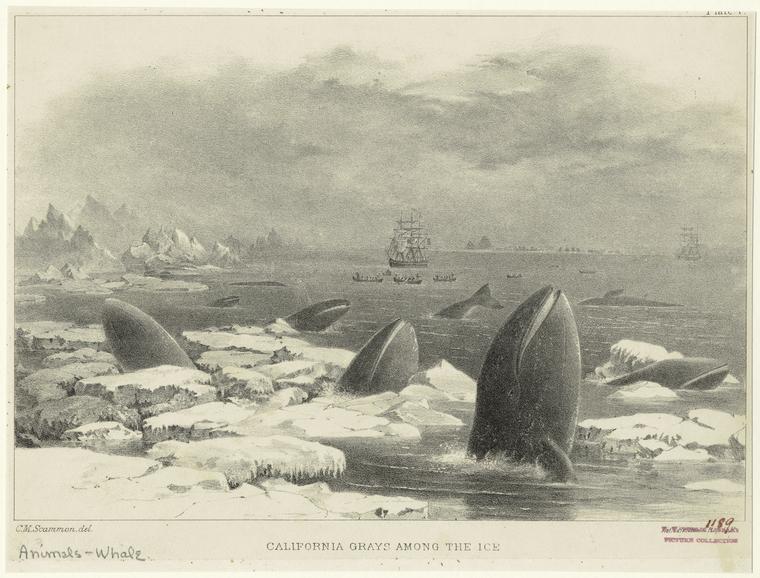

Despite their epic travels, gray whales like to stick to the coast — usually venturing no more than 30 kilometers (20 miles) offshore. Their coast-hugging habits made them easy targets for early whalers in Europe, Asia and the Americas. In the North Atlantic, centuries of human hunting decimated gray whales. Exceedingly rare by the beginning of the 1700s, the Atlantic population went extinct sometime around the middle of the century.

In the Western North Pacific, a remnant population of a little over 100 hangs on off the coasts of Russia, Japan and China. This group of western whales was thought to be extinct until 1972, and have remained critically endangered since their rediscovery. But the number of adult females grew from 27 in 2004 to 43 in 2015 — a hopeful sign that conservation efforts might be working.

Whalers also pushed Eastern Pacific gray whales to the edge of extinction. According to genetic studies, around 100,000 individuals once churned up and down North America’s western coastline. But a century and a half of whaling nearly wiped these giants out, until a ban on commercial whaling was enacted in the 1940s. Their recovery was spectacular. By 1994, the whales were so abundant they were taken off the United States’ endangered species list.

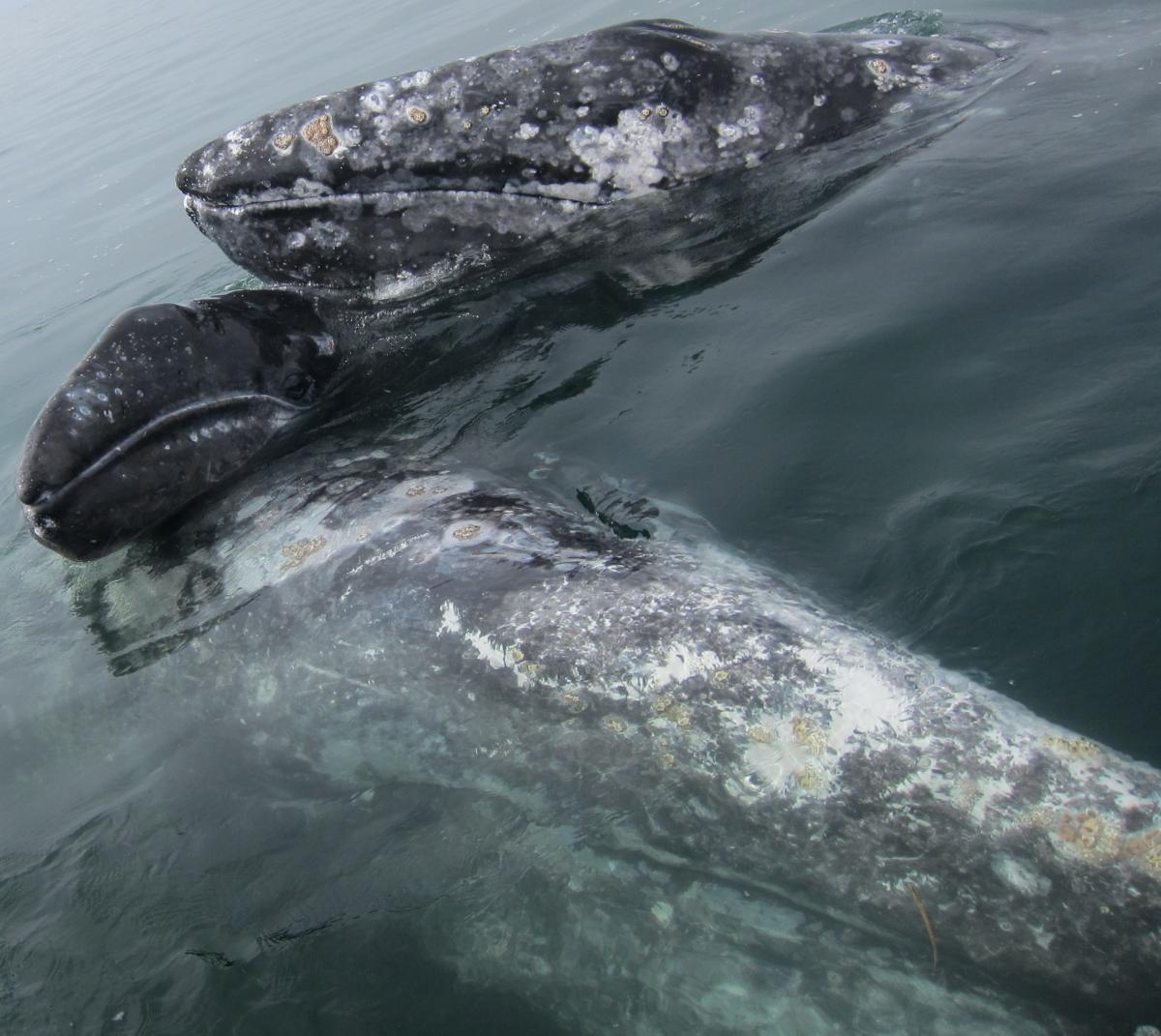

Once the site of slaughter, the calving lagoons in Baja California now host a thriving whale-watching industry. The whales, for their part, seem to have forgiven us. Mothers and calves are famous for sidling up to tourist boats, soliciting snout scratches and tongue rubs — apparently just as delighted by us as we are by them.

But change is in the water for gray whales. The Arctic Ocean is warming faster than just about any other place on earth. This spells big shifts in the muddy banquet halls that these whales visit each summer. As the Arctic loses its sea ice at a rapid clip, researchers are not yet sure whether this will mean more or less food for whales — but it may have already opened up new routes for cetacean travel.

In 2010, a wayward gray whale was spotted off the coast of Israel. In 2013, another individual popped up in the waters off Namibia. These whales may have swum over the top of the world, beckoned by the call of ancient migratory routes. Or maybe they were just hungry.

Fossils of gray whales date back 2.5 million years. Humans, by contrast, have been around for just 200,000 years. Over their evolutionary lifespan, gray whales have survived dozens of cycles of hot and cold, perhaps by adapting their diets and feeding methods.

As the world warms, researchers hope that gray whales might have a few tricks up their sleeves. With an uncertain future ahead, they’ll need brains, brawn and a few tongue rubs for good measure.