October 8, 2015

Breathing Behaviors, Fishing Gear Could Determine Shark Survival Rate During Capture

BY: Alison Shapiro

Did you know that there isn’t just one way sharks can breathe, and the way in which a shark breathes could affect its chances of surviving during fishing capture?

Some sharks can breathe by taking water in through their mouth using muscles in their cheeks, then absorbing oxygen as they push the water out through their gills. These types of sharks, referred to as stationary respirators, do not have to actively move much to breathe this way. Other shark species must maintain a constant swimming motion or they will drown.

Researchers in Australia from Monash University, in collaboration with Flinders University, identified various respiratory modes of different shark and ray species, and discovered that those modes may work for or against these fish species when captured by fisheries worldwide.

Their findings were published in the fisheries journal, Fish and Fisheries.

Across the globe, some sharks are intentionally targeted and others are accidentally caught in fishing gear as bycatch. There is a huge worldwide decline in shark and ray populations from these species being hooked, entangled, or swept up in fishing gear.

“Sharks can die during capture owing to physical injury or suffocation, but until now the sensitivity of different species has not been well understood,” lead researcher Derek Dapp told phys.org.

The research team analyzed more than 80 shark and ray species caught by commercial fishing gear including longlines, gillnets and trawls. Respiratory mode and fishing gear type were evaluated to determine how the two factors combined impact species’ survival. Public data on immediate mortality percentages, as well as post-release morality rates (animals that are released alive, but die later due to injury from capture) of 40 species, helped the team gain greater clarity on elasmobranch (the subclass of cartilaginous fish that include sharks, rays and skates) mortality during accidental capture.

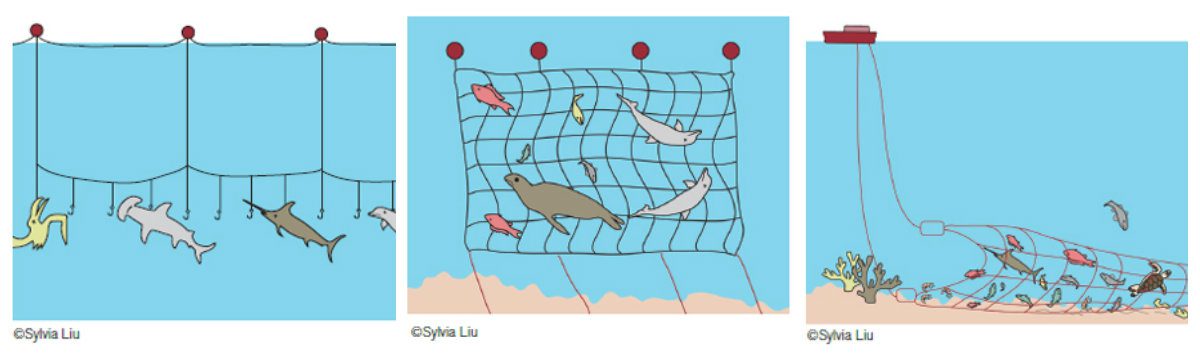

Longlines extend up to 50 miles in the water with hundreds or thousands of baited hooks hanging from the main line, often attracting an array of non-targeted species that could die by the time the line is retrieved. Gillnets, on the other hand, are invisible walls of net— some stretch a mile in length and drift 200 feet below the ocean’s surface and others are smaller and tethered to the ocean bottom— that entangle many species of wildlife as they pass by. Lastly, bottom trawling involves enormous, weighted nets that drag across the seafloor to capture many different fish species that live near the ocean bottom, but they often capture everything in their paths and destroy habitats at the same time.

Taking their research one step further, the team then factored in the species’ respiratory mode. Total discard mortality percentages of stationary-respiring species— those that are able to breathe while resting using a respiratory opening called a spiracle— were much lower than for species that need to continuously swim forward to breathe.

For example, the average mortality rates of active sharks in the study that were caught in trawls, like the hammerhead and mako, was 84 percent compared to a mortality rate of 41 percent for stationary species like the nurse shark.

The highest mortality rates for both resting and continuously moving sharks were found in those caught in trawls, followed by gillnets (25 and 79 percent, respectively) and then longlines (7 and 49 percent).

While catch of shark species across all fisheries must be addressed to reduce injury and death, the study suggests that the type of breathing method can be used to help protect shark species for which little to no information is available.

Researchers hope the results of their study will enable scientists, along with fishery managers, to develop better management strategies for protecting vulnerable shark and ray species.

The study also highlights the impact of fishing activity on the health of many species of sharks and rays, citing that if bycatch does not decrease (particularly of animals that are injured when released and die later) shark and ray populations globally may decrease even despite existing regulations.

The researchers encourage additional studies to better understand post-release mortality and total discard mortality.

The study concludes by stating that changing gear types or fishing locations to minimize bycatch may be a more effective management strategy than one focused on releasing the animal back into the water when caught.

Oceana is very concerned with impacts of bycatch and is working diligently with state and federal fisheries managers, state legislative members and Congressional representatives, fishermen, additional environmental groups, and others to identify ways of reducing bycatch across different fisheries. We are pushing for changes to fishing gears and management strategies that reduce the number of marine animals captured and increase the chance of survival for animals that are released alive when accidentally caught, while maintaining sustainable fisheries that provide fresh seafood products.