May 30, 2017

10 years in the making, a major win for West Coast wildlife could change how we protect the ocean

BY: Allison Guy

From January through July, the Pacific Ocean’s lonely Midway Atoll comes alive with hundreds of thousands of albatross families. Young adults flirt, established couples dance and gray-fuzzed chicks dot the grass like picnickers at a summer concert. When a breeze ruffles the greenery, hundreds of babies pop out of their nests to flap their stubby wings.

Among Midway’s temporary residents is the Laysan albatross Wisdom. At 66, she’s the oldest known wild bird. She’s also one of the avian world’s most skillful moms. Last February Wisdom hatched what’s estimated to be her 30th or 40th chick — no small feat for an albatross. These birds lay just one egg a season, and both parents have to work around-the-clock for seven months to raise their chick to adulthood.

To load up on top-quality groceries for Baby, albatross parents have to travel very, very far: 3,000 miles, give or take. Many Midway nesters sail to the West Coast of the United States, where the powerful California Current fuels a glittering buffet of fish, squid and krill. These high-fat, bite-sized “bait” fish and their eggs make for perfect (if stinky) food for a growing chick.

Around the world, however, bait fish are falling victim to massive “reduction” fisheries that grind them up to feed farmed fish and livestock. A decade ago, it seemed like the California Current could become another casualty of the mounting demand for tiny fish. But last April, a final regulation put hundreds of bait species on no-fishing lists in ocean waters off California, Oregon and Washington. It’s the capstone of a decade of work on the part of Oceana and allies to protect these species from the development of new fisheries.

According to Geoff Shester, Oceana’s California campaign director and senior scientist, this region-wide action is a sea change in how we manage the ocean. In the past, we’ve aimed to extract as many fish as a given stock could withstand without considering how this could derail ocean ecosystems. Now, Shester said, “we’re beginning to recognize that some species are more valuable if we leave them in the water.” This holistic strategy means more food for wildlife and fish, more reliable catches for fishermen and a better shot at shepherding the sea through climate change. It’s also good news for albatross chicks.

Taking the bait

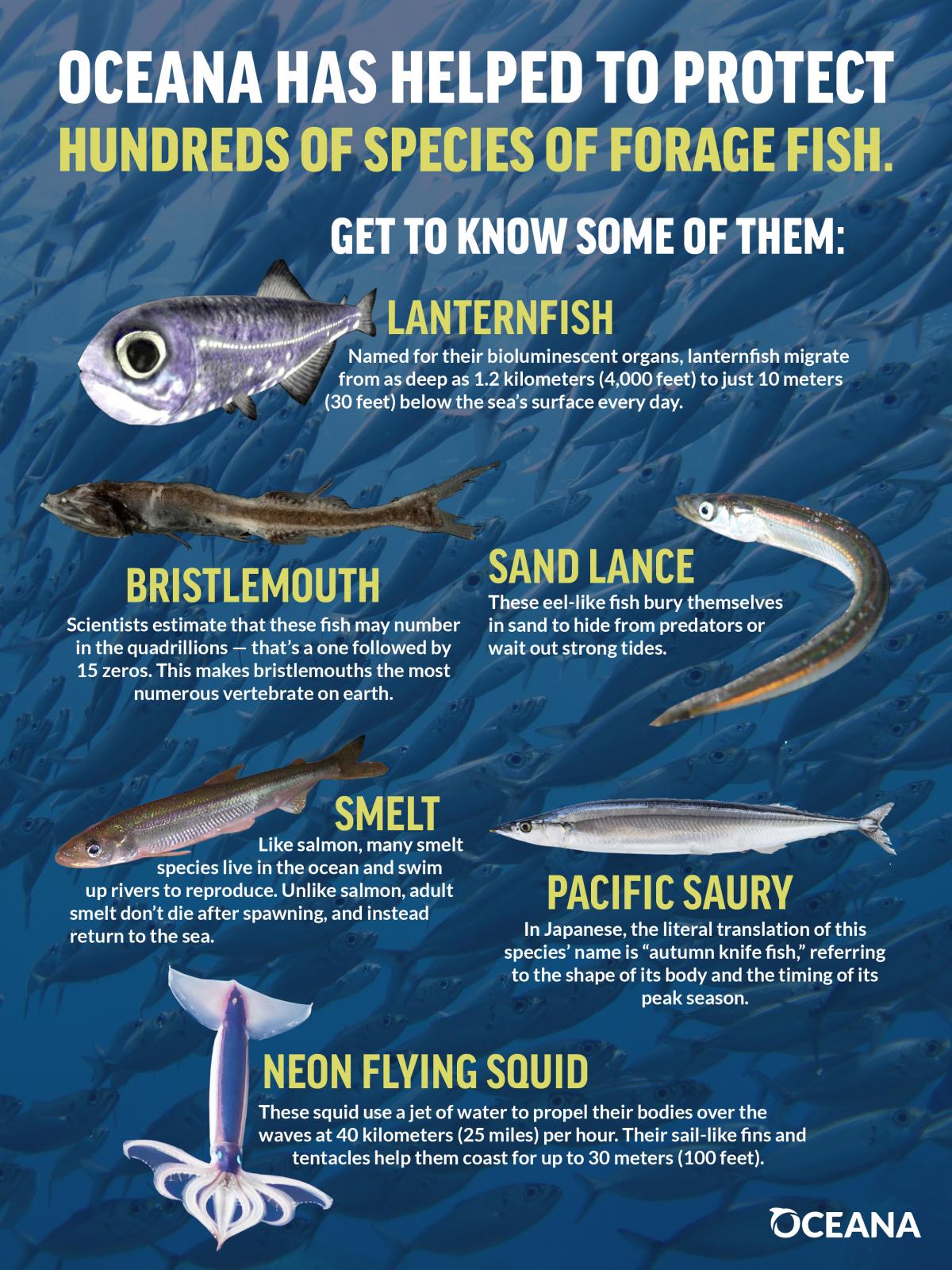

The California Current begins off British Columbia, runs south along the west coast of North America and heads out to sea off the Baja California Peninsula in Mexico. This nutrient-rich current sustains a diverse group of fish, krill and squid collectively known as “bait” or “forage” species. These animals range from the familiar — sardines and anchovies — to the bizarre. Eulachon, for example, are so oily that they can be dried and used as candles. And neon flying squid, Shester’s favorite, spit out jets of water to zip over the waves.

These little fish help support one of the most biologically productive regions on the planet, so it’s not surprising that more than albatrosses show up for the feast. Humpback, fin and blue whales migrate along this current, sieving up to a half-ton of food with every gulp. Salmon grow fat on the current’s forage species. And California’s most raucous residents — sea lions, that is, not celebrities — make a year-round living on this offshore bonanza.

Back in 2004, fishermen and scientists in California were growing concerned that krill, one of the current’s key players, could become the next target of commercial fishing. That scenario was already unfolding in Antarctica, where a burgeoning krill fishery had left many scientists alarmed. “They were just vacuum-sucking up the whole basis for the ecosystem,” Shester said.

Krill might be most familiar to consumers as krill oil supplements, but these crustaceans ar e primarily ground up and processed into oil and powdery meal for livestock feed. This mirrors what happens to forage species the world over. Small fish overwhelmingly fill animal troughs, not human bellies. In Peru, for example, only 2 percent of the millions of tons of anchovy landed each year winds up on dining tables. The rest is “reduced” into fishmeal and oil.

e primarily ground up and processed into oil and powdery meal for livestock feed. This mirrors what happens to forage species the world over. Small fish overwhelmingly fill animal troughs, not human bellies. In Peru, for example, only 2 percent of the millions of tons of anchovy landed each year winds up on dining tables. The rest is “reduced” into fishmeal and oil.

Californians worried that the development of a krill fishery could devastate the state’s marine ecosystem. Krill not only famously feed whales, but also commercially valuable species including salmon, halibut and rockfish. The concerns about overexploitation were colored by past fisheries collapses on the West Coast, including a devastating sardine crash in the 1950s.

Commercial krill fishing was not some distant threat. For krill and other as-yet untouched forage species, Shester said, “It was only a matter of time before massive fisheries opened up.”

Where there’s a krill, there’s a way

In 2004, California marine sanctuary managers asked the West Coast’s regional fishery council to ban krill fishing inside sanctuary boundaries. But calls to protect krill didn’t pick up steam until two years later, said Ben Enticknap, Oceana’s Pacific campaign manager and senior scientist. Spurred by Oceana advocacy, the Pacific Fishery Management Council agreed on a region-wide krill ban at its March 2006 meeting. The ban covered all waters from shore out to 200 miles along the entire U.S. West Coast.

After this meeting, the council passed its recommendation for a krill ban to the federal fisheries agency, expecting it to approve and enact the rule. Enticknap explained that it’s vanishingly rare for the National Marine Fisheries Service not to take a regional council’s advice. But in a move that surprised many, the fisheries service “dug in its heels,” Enticknap said, and refused to implement the recommendation.

This was partially the fault of the administration at the time — President Bush was not known for his innovative approaches to conservation. But this was also the first time that a regional council recommended a catch limit of zero for a species on the basis of its importance to the ecosystem, Enticknap said. Some federal officials were afraid of the precedent the krill rule would set: Namely, that for certain vital species, the most you can sustainably harvest is nothing.

Crisis management

It took three years and a change of administration for the krill ban to take effect. With this, Oceana got exactly what the fisheries service under Bush had feared — a precedent. Almost immediately, Oceana and its allies at other conservation groups lobbied members of the Pacific Fishery Management Council to protect other groups of as-yet unfished forage species.

The goal was to put these animals off-limits to new fisheries until data could prove that fishing any of them on a commercial scale would not hurt their predators or the rest of the West Coast ecosystem. All in all, the Oceana’s proposals would protect around 70 percent of the forage species by weight off the West Coast, amounting to tens of trillions of individual animals.

This was a tall order for two reasons. The first was practical. The 320,000 square miles of West Coast waters are controlled by four separate entities: the federal government, and the states of California, Washington and Oregon. States control the ocean from the shore out to 3 miles, and the federal government manages the remainder out to 200 miles. Each of these governments would require a different strategy.

The second was philosophical. U.S. laws are generally set up to encourage the development of new fisheries, not prohibit them. Often, fishing is already well underway before scientists can figure out if it’s sustainable. This sparks an acrimonious cycle of conservation groups, government and industry fighting over catch quotas, the effects of climate change and whether to fish at all if animals like sea lions and pelicans are starving, Shester said.

Enticknap agreed: “Too often we’re in a situation where conservation actions are taken only in response to a crisis.”

Reversing the burden of proof — from environmentalists proving harm to fishermen proving no harm — helps to nip disaster in the bud. This proactive, ecosystem-based approach aims to better account for the dizzying web of interactions between all the ocean’s animals, not just on a species-by-species basis.

Oceana’s proposals found a receptive audience at the Pacific Fishery Management Council. In 2013, the council agreed on a comprehensive plan to add ecosystem considerations to its current management strategy. The first of these “ecosystems initiatives” was a doozy: protecting hundreds of unfished forage species in federal waters from California to Washington. In 2015, the council adopted this initiative, and the next year the National Marine Fisheries Service enacted it. At around the same time Oceana initially approached the council, Shester and Enticknap were working with fish and wildlife agencies in Oregon and California to implement similar rules for state waters (Washington has had a precautionary forage fish management plan since 1998). Oregon’s Fish and Wildlife Commission unanimously adopted a forage fish plan in 2016. And last Easter, the Oceana team got more than chocolate and eggs in its basket — the California Department of Fish and Wildlife followed Oregon’s lead by finalizing its own forage fish regulations.

Baby on the run

Oceana’s work to better manage West Coast forage species is part of a long-term vision to expand ecosystem considerations for forage fish to the rest of the United States. The concept seems to be catching on: In March, fishery management bodies unveiled a proposed rule to protect several unfished forage species in the Mid-Atlantic.

Shester explained that the ultimate aim is to fish more like an ecosystem operates. Ocean predators have “millions of years of experience” switching from prey to prey as some dwindle and others multiply. The fishing industry, too, should stop targeting certain species as they become rare, and focus on more abundant alternatives. This tactic has helped marine animals weather changing climates, and it may aid us as our climate warms too. “Being able to fish more like the predators out there eat,” Shester said, “that’s really our challenge.”

This holistic approach to fisheries means sustainable income for fishermen and dependable seafood for diners. But it also means that albatrosses — and the scientists that study them — have one less thing to worry about.

A month after California announced its decision to put hundreds of forage species off-limits to new fisheries, Wisdom’s chick had become so active that it was getting hard to find. The nest was empty when Wieteke Holthuijzen, an environmental scientist numbering among Midway’s 50 or so human residents, went out to snap a photo of the famous chick. But Holthuijzen wasn’t particularly concerned. The 7-pound baby was no doubt nearby, and would come waddling back to the mud-walled nest once mom or dad arrived with dinner.