December 8, 2020

Ask Dr. Pauly: How do gillnets work?

BY: Daniel Pauly

There are different ways to catch fish, and their differences are as useful to know as that between hunting rifles and AK47s. In principle, gillnets should be highly selective, i.e., catch fish of a particular species and size, and avoid undesired fish.

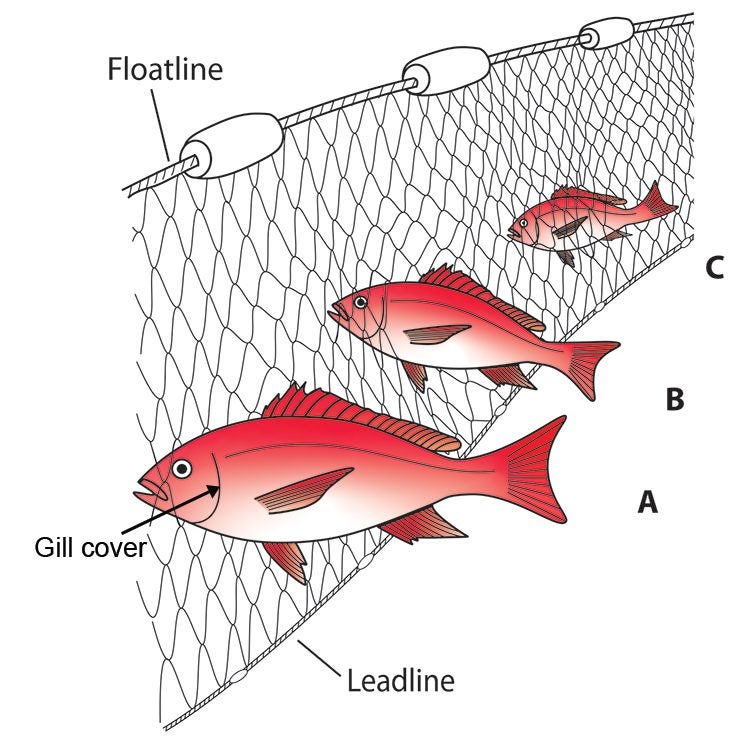

Fish are caught in a gillnet that hangs down stiffly when they have a head small enough to enter the mesh of the net, but a body too big to pass through that mesh; in this case, the fish get stuck – not by their gills, but by the posterior side of their gill cover (see arrow in Figure 1 below).

Also, in principle, smaller fish can pass through the mesh holes, and bigger fish would not be caught either because their heads could fit through the mesh, but their gill covers could not (again, see Figure 1).

However, this works only if the gillnets hang stiffly in the water column, either while they are anchored at specific spots or left to drift with the currents (in which case we speak of “driftnets”). If gillnets do not hang stiffly – and all fishers know how to make them hang loosely – they work as a swaying wall of death that entangles every animal, large or small, that pushes against their folds.

Thus, a gear designed to catch 20-inch snappers ends up catching everything from 6-inch sardines to 6-foot-long sharks along with assorted sea turtles and dolphins. Or, put differently, a gear designed like a precision hunting rifle works like a forest-flattening bomb.

In response to the demand of fishers using selective gear, such as hooks and lines, and of civil society in Belize, a country for which marine fishes are a major touristic asset, Oceana has, for years, pushed for a nationwide gillnet ban. On August 20, 2020, the Government of Belize signed a joint agreement to ban gillnets and offer fishers compensation to surrender their gear (for more details, read Oceana’s feature here).

There is also a global dimension to this: Very deep driftnets that had lengths of tens of miles were for decades commonly deployed in the high seas to catch tuna beyond the jurisdictions of coastal countries.They were outlawed by the United Nations in 1989 because of the damage they inflicted, but they continue to be used widely, albeit illegally. They are most often used to catch swordfish (and kill thousands of other marine animals), notably in the Mediterranean.

While a gillnet ban is a huge victory for Belize, this deadly gear is still in use in many other parts of the world. However, both Belize and the United Nations have shown, by outlawing giant driftnets, that it is possible to reverse course and protect marine diversity rather than mindlessly destroy it.

This story appears in the current issue of Oceana Magazine. Read it online here.