March 15, 2018

Belize became the world’s first country to reject all offshore oil. Here’s how it happened.

BY: Allison Guy

It sounded like rolling thunder.

At first, Jamani Balderamos wasn’t worried. Sudden, short-lived storms are common off Belize’s Turneffe Atoll, where Balderamos was leading tourists on a scuba dive. But a second rumble of thunder followed, then another and another, each spaced 10 seconds apart.

Balderamos realized it wasn’t thunder, but the tell-tale detonations of seismic airguns. Ships tow these industrial devices as part of the process for finding offshore oil deposits.

“I noticed the fish became kind of scared. They started darting all over the place,” Balderamos said. The blasts got louder. He signaled for his group to get out of the water, unsure if the airguns were dangerous. “You could actually feel the reverberation going through your body. I could feel it in my chest.”

Days earlier, on October 12, 2016, Oceana had been tipped off that a seismic ship was bound for Belize. After the organization shared this news with the public, long-simmering opposition to offshore oil boiled over into outrage, said Janelle Chanona, the head of Oceana in Belize. The country’s tourism economy relies on a thriving ocean — free of airgun blasts, oil rigs and beach-coating spills.

The intensity of the outcry threw a years-long campaign to ban offshore oil into overdrive, Chanona said. “I don’t think anyone was really prepared for the visceral reaction.”

A bitter spill

Sometime in the mid-2000s, unbeknownst to most citizens, Belize’s Geology and Petroleum Department had published maps revealing that the entire country had been carved up into oil concessions, including marine monuments and the famous Blue Hole formation. The maps remained niche knowledge for researchers and oil companies until 2010, when tragedy struck 1,200 kilometers (800 miles) to the north.

On April 20, BP’s Deepwater Horizon platform exploded, killing 11 people and unleashing 200 million gallons of toxic oil into the Gulf of Mexico. Billions of dollars were lost as fishing withered and tourists vacationed elsewhere. “Everybody really realized: I had no idea it could be this bad, and this scary,” Chanona said. “That’s when a national consciousness about the inherent dangers of offshore oil kicked in.”

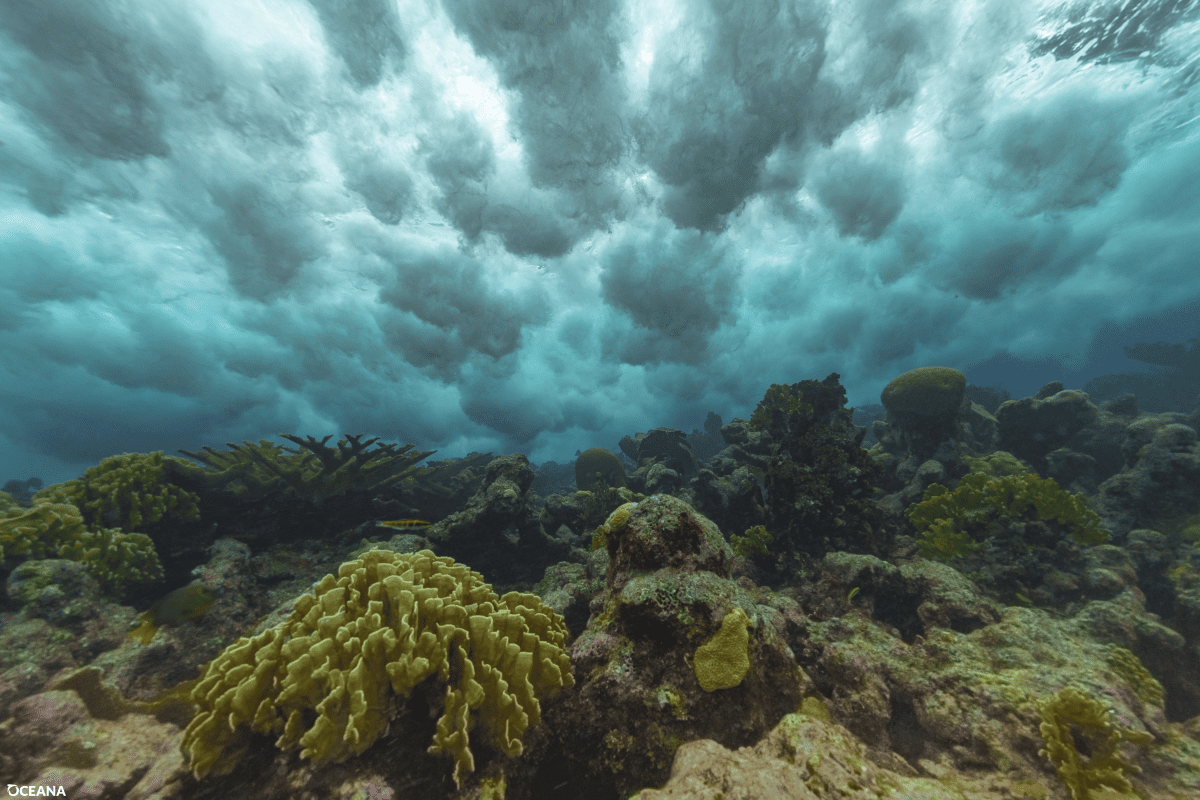

Oceana’s Belize office, then only a year old, had been campaigning to boot bottom trawling and other forms of destructive fishing from the country’s 300-kilometer (190-mile) barrier reef. The team realized that a toxic spill, slicking corals and poisoning wildlife, could render any marine conservation efforts moot. They publicized the Geology and Petroleum Department maps, along with the fact that the government was actively courting offshore oil interests.

For many Belizeans, these were grim revelations. A giant spill would cripple the country’s economy. Thirty-five percent of all jobs in Belize depend on tourism, much of it centered on sport fishing, scuba diving and other activities that rely on a healthy ocean. Another 15,000 are tied to the seafood sector — huge numbers in a country of just 400,000 people.

Even ignoring the risks of a spill, Belizeans would see few economic benefits from drilling, explained Imani Fairweather-Morrison, a Belizean Oak Foundation program manager who supported Oceana’s anti-oil efforts. “It was appalling to everyone,” she said.

The damages from drilling would go deeper than money. The barrier reef is a pillar of national pride, Chanona and Fairweather-Morrison agreed. A string of seven UNESCO World Heritage sites along the reef host blue-footed boobies, whale sharks and vibrant coral atolls.

“As small as we are, we can lay claim to this amazing resource,” Chanona said. “The reef is an untarnished source of pride. We are a developing nation with so many challenges, and so many issues. But we have our reef.”

Something in the water

Following a victory that banned bottom trawling in Belize, stopping offshore oil became Oceana’s number one priority. The team flew Elsa Paz, then the mayor of San Pedro — an island town on Ambergris Caye, Belize’s main tourist hub — to the Gulf of Mexico, where she saw and smelled the spill in person. The mayor carried her disgust back home, transforming San Pedro into a bulwark against offshore oil.

In 2011, the team cofounded the Belize Coalition to Save Our National Heritage, which eventually grew to almost 40 local and international partners. At first, the coalition focused on drumming up grassroots support for a ban among fishermen and tourism operators, two groups with the highest stakes in a healthy ocean.

Soon, however, it became clear that the coalition’s community presentations and print, TV and radio ads were reaching a bigger audience. It “was awesome that we were getting more support from laymen” than expected, said Amanda Burgos-Acosta, the director of the Belize Audubon Society, a coalition member.

In 2012, the coalition harnessed public sentiment to force a national referendum on offshore oil. Fifteen-thousand signatures are required to trigger the decision. Oceana and its allies collected 20,000. But the disqualification of 8,000 signatures eliminated the possibility of an official referendum. Undeterred, the coalition launched the “People’s Referendum,” staffing 51 polling stations across the country.

Burgos-Acosta recalled a conversation with a man who came to vote with his baby daughter. “I’m here to put my vote and my voice to this,” he told her, “because I want my baby to enjoy the sea the way I do.” She added: “To him, it was a personal connection.”

Almost 30,000 people voted, a turnout Burgos-Acosta called “phenomenal.” Ninety-six percent of votes cast were in favor of a permanent ban on offshore oil. But this flood of public support failed to persuade the government. For the next three years, little changed.

The coalition kept the pressure on. Fairweather-Morrison, of the Oak Foundation, praised Chanona’s tenacity. “She never let up. She would always knock, always call, always keep the lines of communication open,” she said. “It’s extraordinary really, the understanding that you hold more with an open hand than a clenched fist.”

Seismic upset

Then in December 2015, hope flickered into focus: The government announced that it would permanently ban offshore oil exploration along the barrier reef and within World Heritage sites. But the new protections only covered 15 percent of Belize’s marine territory. It was a step in the right direction, Oceana and other coalition members said, but it wasn’t enough.

Then, on October 12, 2016, Oceana received an alarming phone tip: The government had approved a contract for oil exploration a kilometer off the reef, despite its public promises.

Days later, the Oceana team accessed satellite tracking data and discovered that a seismic ship had already entered Belizean waters. Oceana and coalition called on the government to postpone airgun blasting until the public had a chance to weigh in.

But on October 18, satellite maps showed the ship tracing a back-and-forth pattern near Turneffe Atoll — movements characteristic of seismic airgun use. The team’s suspicious were confirmed when a local aboard a light plane snapped photos of the vessel towing bubbling airguns, the same ones that divemaster Jamani Balderamos heard as thunder.

The next day, Oceana and its allies went live with this evidence. Tourism-dependent San Pedro erupted with anger. Guides and business owners debated shutting down the country’s tourism industry in protest. Locals packed a raucous meeting with government officials at a San Pedro hotel, demanding answers that were in short supply.

“We as NGOs didn’t even have to say anything, because the people were so vocal about what they wanted. And the biggest thing they wanted was the boat out of Belizean waters,” Burgos-Acosta said. “I think at that point, the game kind of changed.”

Minister of Tourism Manuel Heredia, who also serves as a local representative for San Pedro and surrounding areas, was among the crowd at the meeting. Afterwards, he spoke with Prime Minister Dean Barrow, who ordered the seismic ship out of the country the next day.

Coalition members noted the significance of the anti-seismic outcry. “The public’s insistence to be meaningfully consulted on this issue has and will never waver,” Chanona said. “That was what made the difference.”

In August 2017, following consultations with Oceana and the Belize Coalition, Prime Minister Dean Barrow announced his government’s plans to institute an indefinite moratorium on offshore oil exploration and drilling in the country’s marine territory.

The bill was introduced on December 9, and received bipartisan support in Belize’s House of Representatives and unanimous endorsement in the senate. On December 30, the moratorium became law, making Belize the world’s first country to reject all offshore oil

Fairweather-Morrison praised the decision. “When you see places like Belize standing up, making this sort of choice about its path for development,” she said, “it’s really heart-warming and encouraging.”

There are still big battles ahead for Belize’s reef. Overfishing, irresponsible coastal development and climate change are major concerns. “But for now, stopping offshore oil has put Belize in the international headlines for the right reason,” said Chanona. “Now the world knows that if the oil lobby ever comes knocking again, it will be answered by a healthy dose of Belizean pride.”