July 12, 2023

Beneath the Fjords

BY: Sarah Holcomb

The campaign to protect Patagonia from Chile’s salmon farming industry

A young veterinary student embarking on her thesis, Dr. Liesbeth van der Meer was faced with a decision: What type of animals did she want to work with? The way she saw it, her options were large animals like horses and cows or small animals like cats and dogs. But then she heard about something new called “salmon aquaculture” that piqued her interest.

“I love animals, and it was very hard for me to deal with people,” she remembers, laughing. “So I said, why don’t I go into fish?” An extra perk: working in aquaculture would mean relocating to Chilean Patagonia, famous for its glacial fjords, temperate rainforest, and pristine waters.

Today, van der Meer is Senior Vice President at Oceana in Chile. Salmon aquaculture has grown into Chile’s second-largest industry. Chile is also home to the second-largest salmon aquaculture operation in the world, behind Norway.

But in 2002, salmon aquaculture was still nascent. Van der Meer decided to do her thesis at the country’s first major salmon aquaculture production facility, and after finishing it, joined the company’s staff as a veterinarian.

Van der Meer saw aquaculture – essentially breeding fish and other marine organisms – as a positive thing for the world. But all aquaculture is not equal. Because salmon are not endemic to Chile, they have no natural predators, which means that when a fish leaves the pen where it is growing, the salmon can cause great ecological harm in the surrounding waters. As van der Meer learned more, the then-24-year-old had questions. Soon after, the fish started dying.

Telling the truth

Salmon are among the few fish considered “anadromous” – born into fresh water, they stay in fresh water for anywhere from a few months to a few years (varying based on species) before migrating to the ocean. Then they return to the fresh water to spawn, famously travelling upstream hundreds or even thousands of miles.

Aquaculture mimics this natural process. In the southern regions of Chile, far from the places where wild salmon swim in the Global North, salmon start out in land-based freshwater farms. The fish are then moved into a calibrated mixture of fresh and saltwater, and finally transferred to pens just off Chile’s southern coast in the Pacific Ocean.

But something was off at the facility where van der Meer worked. Stressed by the tight pens and suffering from a flesh-deteriorating fungus, the salmon started getting sick and dying off.

The solution? Antibiotics.

“We used this product called ‘malachite green,’” van der Meer says. In Europe, the substance had been banned after research showed the chemical could cause cancer in humans. Chile prohibited malachite green starting in 2001. But when other treatments didn’t work, “we kept using it quietly,” van der Meer says. She didn’t feel right about it, now knowing the health risks.

When a manager arrived at the facility from Norway, van der Meer didn’t hide this information. She told him that they continued to use malachite green. Her boss was not pleased. “And of course,” she says, “I was fired.”

Van de Meer was angry. As a veterinarian, it was her responsibility to analyze and warn about risks of disease or chemical misuse. She stood by her decision to tell the truth, even though it meant losing her well-paying job, leaving her “house in paradise,” packing up her life and moving with her baby daughter back to Santiago.

“Remember me – someday I’ll be back,” she told her boss the next day. She spoke the words in frustration, but fate would make something more of them.

Underwater factory farms

Salmon aquaculture production has nearly tripled since 2000. The fastest growing food production sector, aquaculture has cornered 70% of the global salmon market. Previously a luxury food, it is now part of the popular diet in Japan, the United States, and Europe. In 1982, Chile’s salmon production amounted to just over 300 metric tons. In 2021, Chile produced nearly 1 million metric tons, most of which was exported.

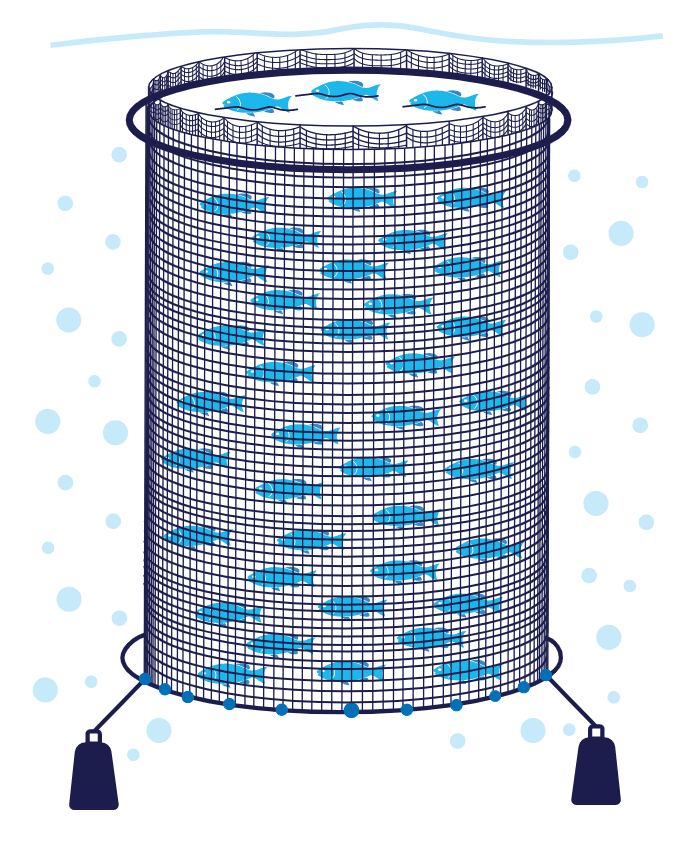

Unlike factory farms for poultry or pork, which create massive eyesores on land, salmon aquaculture can hardly be noticed from above. Looking out at the fjords of Patagonia, just a trace of the tops of cages are visible; the real impact reaches six stories below the water’s surface, where a million fish can live in each salmon farm.

The cages extend deep down to the seabed, home to species such as sea stars, sea cucumbers, crustaceans, coral, and microorganisms. For years, the lack of visibility meant few understood what was happening in the waters below, but divers and scientists have since delivered disturbing portraits of declining marine life.

For 10 years, marine biologist Vreni Häussermann, who dedicated her career exploring the biodiversity of Chilean Patagonia, and a team of researchers surveyed marine life at a site in the Comau Fjord and found the ecosystems deteriorating. Oxygen levels dropped due to contamination and pollution of the waters. Although more than 40% of Chile’s national waters are under some kind of environmental protection, concessions have been granted that allow access to the salmon farming industry. Thirty percent of these concessions lie in marine protected areas, including many sites in biologically rich Chilean Patagonia.

Salmon farming has created severe problems for these ecosystems. In 2008, the infections salmon anemia (ISA) virus created a social and ecological crisis. In 2016, harmful algal blooms in southern Chile killed about 27 million salmon and trout. Other devastating algal blooms followed, and many raised concerns on the local and national level.

Some aquaculture, when properly located and managed, can benefit society and pose minimal threat to ocean ecosystems. But unlike the aquaculture of organisms like seaweed and bivalves, carnivorous ocean pen aquaculture – the salmon farming kind – requires chemicals, releases pollution, threatens the country’s artisanal fishing, and risks fish leaving pens and destroying local ecosystems. Simply put, it can be toxic.

The trouble with antibiotics

Van der Meer’s early career experience didn’t turn her away from aquaculture; instead it put her on a path to studying resource management and sustainability. This journey took her to Canada, where she learned more about how pesticides and antibiotics used in aquaculture can pose dangerous problems to the health of oceans – and humans.

Chilean salmon has earned a reputation, not for its flavor but for its antibiotics. Chilean salmon aquaculture uses large amounts of antimicrobials – primarily the antibiotic Florfenicol, used to treat bacterial diseases. Antibiotics are formulated as pellets and dropped in the water, but the fish aren’t able effectively metabolize them. They eliminate the antibiotics into the water.

Moreover, some antibiotic feed goes uneaten, sinks into the seabed, and spreads out into the environment. The majority of antimicrobials administered to the fish end up in nearby environments, reports have found. When scientists tested these sites, they found antimicrobial-resistant bacteria and antimicrobial resistance genes.

In 2009, Chile’s salmon industry was using roughly 385 metric tons of antibiotics, 600 times more than Norway, the top producer of farmed salmon in the world. Chile’s antibiotic use reached a peak in 2015, when researchers found up to 600 grams of antibiotics were used per one metric ton of salmon produced in Chile, compared with .39 grams per metric ton used in Scotland and Norway.

Companies have since reduced the amount of antibiotics they use per metric ton of salmon in Chile. Because the industry is growing, however, total antibiotic use has climbed according to the latest report from Sernapesca (Chile’s National Fisheries and Aquaculture Service). These antibiotics have affected other animals close to aquaculture sites, such as shellfish.

The effects don’t end in the water. There’s a potential link between antibiotics used in aquaculture and increased bacterial resistance in humans – a public health threat that can lead to dangerous virus outbreaks and increased mortality.

See you in court

In Canada, van der Meer started working with Oceana Board Members Dr. Daniel Pauly and Dr. Rashid Sumaila, who she credits with helping to shape her own thinking. “How they saw the whole picture was amazing to me, and I fell in love with fisheries,” van der Meer says. She embraced the scientists’ “systems approach,” looking not just at fisheries, but economics and consumer decision-making.

After working with Pauly and Sumaila, she returned to Chile and joined Oceana, initially the only NGO working on salmon aquaculture issues in Chile, as Fisheries Campaign Director. She was eventually paired up with Javiera Calisto to work on a new salmon aquaculture campaign.

Calisto was a young lawyer at the time. Together with van der Meer, she filed the first claim in 2014 to require Chile’s salmon aquaculture industry to make its antibiotics data public through Sernapesca. Companies resisted, claiming that this was proprietary information and releasing it would hurt their bottom line. Calisto set out to prove otherwise.

“We decided to go to the root of the problem,” Calisto says. “We needed to change the law.”

“Most companies use the same antibiotic. It wasn’t a secret. We weren’t asking for details on how they were used,” she says. “We proved accessing this information is important for the public interest because the excessive use of antibiotics can affect local communities and the environment.” She also pointed out that the aquaculture companies were already providing this information to the fisheries service in line with legal requirements.

Calisto and Oceana lost the civil court case. They took it to the court of appeals – and, against the odds, won in 2015. “This was the first big win in accessing information on environmental issues,” explains Calisto, who is now Marine Pollution Campaign Director at Oceana in Chile. “We realized that politically and legally, we created jurisprudence. This was a big deal.”

Now required to make their antibiotics figures public, the companies changed their tactic: delay, delay, delay. By delaying the court, they ensured that by the time Oceana and the public could access the information it would be less relevant.

In 2017, Oceana finally received the data originally requested in 2014. With that information, Oceana showed that some companies were using 14 times more antibiotics than others in Chile – which led the government to set rules around density of salmon farms and put pressure on companies to reduce the use of antibiotics. But they needed more timely transparency to affect change. “We decided to go to the root of the problem,” Calisto says. “We needed to change the law.”

In 2023, Oceana did exactly that.

A full-circle victory

Oceana campaigned for Sernapesca to publish data on antibiotics use every month. The team worked with lawmakers, fellow nonprofits, and even groups within the Chilean salmon aquaculture industry to secure their support. By now, some aquaculture companies published data in their own sustainability reports – though the numbers, unlike the official ones published by Sernapesca, weren’t verified. Oceana campaigned to require Sernapesca to publish data on the use of antibiotics and antiparisitics, mortalities, and the number of salmon produced by company and by facility.

Oceana used not only an environmental argument, but an economic one: The lack of environmental standards is driving down the value of Chilean salmon and damaging Patagonia, a beautiful tourism destination. Meanwhile, with Calisto, van der Meer, and Senior Oceana Fisheries Campaigner Cesar Astete leading the way, Oceana campaigned to create more awareness among the public, explaining why antibiotic resistance impacts health.

Transparency is important, but the team didn’t stop there. They wanted to penalize salmon releases – or, as many call them, “escapes” – which happen due to aquaculture companies’ negligence. Although bad weather is common in Southern Chile, some companies are not using salmon pens designed to withstand it. The storms cause pens to tear apart and sink to the bottom of the sea. Companies also fail to maintain the steel pens, which wear out and crack over time. As a result of these circumstances, salmon are released, introducing threats to the surrounding ecosystem.

“Proving this damage is very complicated – how do you prove that the specific salmon that left the farm harmed the environment? In the new legislation we established a system where if a salmon is introduced into the natural environment, a fine is given because a risk is produced,” Calisto says. “For example, this logic is used in traffic regulation. If you pass a red traffic light but do not cause an accident, you still pay a fine because you’re creating risk.”

Not only did the transparency requirement pass in Chile’s congress, but for the first time, the law considers salmon releases to cause direct environmental damage. The new law will make the industry pay approximately $28 for every salmon that leaves the farm. The last major event in 2019 involved 690,000 farmed salmon entering the marine environment, which now could incur a fine of $19 million USD. Farms that allow releases must suspend their operations. The law also allows local artisanal fishers to catch these salmon, which will further reduce the threat of damage to the marine environment. “We’re happy for this chapter to end, van der Meer says, “but it’s not over yet.”

What comes next? “I think our main worry now is how to decrease [salmon] biomass,” van der Meer says, because “the industry’s expectation is to keep growing.” She and her team are focused on protecting pristine places for good in Chilean Patagonia, such as Katalalixar, ancestral homeland of the Kawésqar people, “so that their great-grandchildren will never see salmon aquaculture there.”

For van der Meer, the latest victory marks a full-circle moment, as she remembers the conversation when she was fired at the aquaculture company years ago. “Little did my boss know that he would see me many years later winning big battles against salmon aquaculture,” she says.

She feels grateful. “I get to fulfill my dreams, work on saving what I’m passionate about, and make that conviction I had when I was 24 years old worthwhile.”