December 11, 2017

This blue-fleshed fish is a conservation success, but its future is far from assured

BY: Ben Goldfarb

If the West Coast’s colorful, bottom-dwelling rockfish have nightmares, the mouth of a lingcod — cavernous, tooth-studded, lethal — must take center stage.

Lingcod lurk among rocky reefs from Baja California to the Gulf of Alaska, and they’re among the coast’s most fearsome predators, patient and indiscriminate ambush hunters that explode from their cover to nab whatever hapless prey swims past. Neither true ling nor true cod, lingcod belong to a family called the greenlings, though in truth Ophiodon elongatus is an evolutionary oddball, the only surviving member of its genus. As the Latin suggests, lingcod have long, eely bodies mottled in brown leopard spots that camouflage them on the seafloor, where they use their winglike pectoral fins to prop themselves up while they wait. But it’s that grinning mouth, wide as the fish itself, that makes lingcod so fearsome. In one video, a lingcod clenches a live salmon, practically its own size, in its jaws, as though trying to figure out whether the unfortunate creature will fit in its belly.

Lingcod may not be conventionally beautiful, but for the West Coast’s commercial and recreational fishermen, there’s hardly a prettier sight than a full-grown “bucket-head” emerging from the Pacific. Adult lingcod commonly weigh up to 30 pounds, and 60-pounders occasionally appear in nets and on lines. Lingcod flesh often has a bluish or greenish cast, but that odd tint disappears when it’s fried or baked, leaving a thick white fillet that ranks among the Northwest’s most underappreciated delicacies. “It’s got a great flavor, it’s a nice meaty fish, and it’s hard to overcook,” says Brad Pettinger, a former commercial fisherman who serves as director of the Oregon Trawl Commission. “It’s a very high-quality fish.”

Lingcod are all the lovelier for their checkered history. Once a dietary staple of coastal American Indians, lingcod became a target for commercial fisheries in the 1870s. Pairs of sailboats dragged trawl-like paranzella nets across California seabeds for flatfish, rockfish, lingcod, and other denizens of the ocean floor, fodder for fish markets springing up around the rapidly growing state. Although some hook-and-line fishermen pursued lingcod in the early 20th century, the fish remained relatively immune to overfishing, as trawlers couldn’t tow nets through lingcod habitat without getting hung up on rocks. That changed in the 1960s, when fishermen outfitted their nets with tires that bounced trawls over reefs, opening the fishery to devastatingly efficient trawlers. The expansion of recreational fishing took a toll as well. In the 1980s, for instance, lingcod supplied more pounds of meat to central and northern California anglers than any other fish.

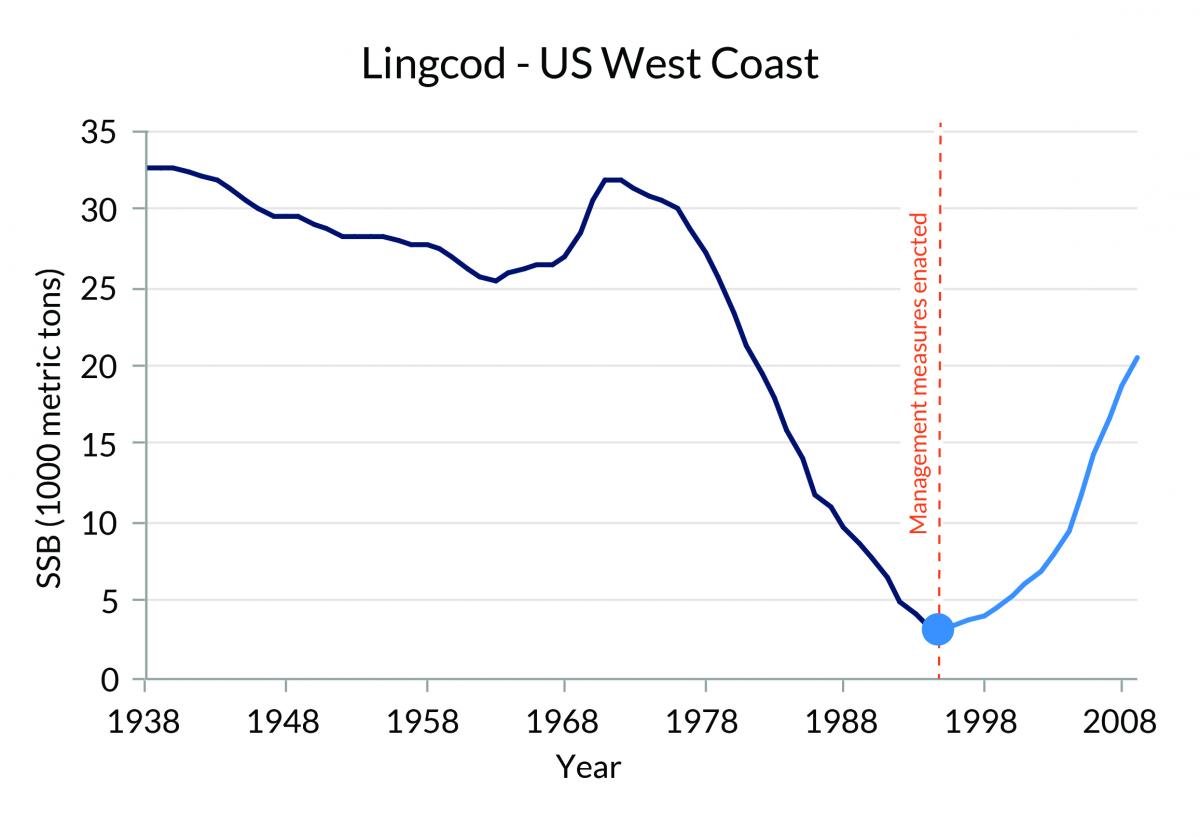

The bounty couldn’t last. Total lingcod landings climbed to around 10 million pounds per year in the mid-80s, then fell by half in the early 1990s. Fishermen turned up at Pacific Fishery Management Council meetings to report dire declines along the Washington coast. Although Oregon, Washington and California tried to forestall disaster — for instance, by setting a 22-inch minimum size limit for recreational fishermen — it wasn’t enough. In 1999, the National Marine Fisheries Service announced that lingcod was officially overfished. Stocks had collapsed to a once-unthinkable 7.5 percent of their historic levels.

Lingcod were hardly the only groundfish — a group that includes lingcod, sole, sablefish, rockfish, and a suite of other flakey, white-fleshed species — depleted by overfishing. Between 1999 and 2002, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) declared a total of nine West Coast stocks overfished, including canary, yelloweye, and widow rockfish. Bycatch had flown through the roof: Over twenty percent of the catch was simply discarded.

Lingcod were hardly the only groundfish — a group that includes lingcod, sole, sablefish, rockfish, and a suite of other flakey, white-fleshed species — depleted by overfishing. Between 1999 and 2002, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) declared a total of nine West Coast stocks overfished, including canary, yelloweye, and widow rockfish. Bycatch had flown through the roof: Over twenty percent of the catch was simply discarded.

In the past, regulators might have allowed the harvest to continue unabated. A few years earlier, however, American fisheries management had gotten a crucial legal overhaul. In 1996, the Magnuson-Stevens Act, the nation’s foremost marine fish law, had been reauthorized through the Sustainable Fisheries Act, a revision that compelled fisheries managers to prevent overfishing and put depleted stocks on strict rebuilding timelines. Lingcod became an early case study for the more stringent MSA. The Pacific Council instituted a 10-year rebuilding plan in 2000 that slashed allowable catches, raised the minimum size limit to protect young fish, and shut down fishing for half the year. Recreational anglers were restricted to just two fish per day.

As intended, the harvest plummeted. In 1997, three years before the rebuilding measures went into place, West Coast fishermen had landed over 4 million pounds of lingcod. By 2001, though, catches had fallen to less than a million pounds per year. The Pacific Fishery Management Council — motivated, in part, by a series of conservation group lawsuits — implemented steps to protect rockfish as well, including restricting the kinds of nets that fishermen were allowed to use and banning fishing in designated Rockfish Conservation Areas, a sweeping network of closed areas along the Pacific Coast. Congress also approved a massive loan to buy out boats and permits, alleviating pressure on stocks.

The regulations were a bitter pill for the fishing industry: By 2000, catch limits had been cut so drastically that the Department of Commerce declared the situation a disaster. But the new rules did the trick. Aided by the rebuilding plan and their own relatively rapid reproduction — males reach sexual maturity in just two years, although females take three to five — lingcod recovered in a hurry. By 2005, four years ahead of schedule, the fish had surpassed rebuilding targets by 60 percent. To be sure, good fortune deserves as much credit as smart management. Pete Adams, the scientist who conducted the grim 1999 assessment, says that favorable ocean conditions during the rebuilding years likely helped more juvenile lingcod survive to adulthood.

Nonetheless, the toothy predator has become Exhibit A for conservationists touting the Magnuson-Stevens Act’s effectiveness. “With the right science, and the commitment of managers under the law to do the right thing, there can be big changes to recover fish populations,” says Ben Enticknap, Oceana’s Pacific campaign manager and senior scientist. “Lingcod is the evidence for that.”

All of this, of course, is Fisheries Management 101. Catch too many fish, and populations decline; catch fewer, and they recover. What could be simpler? Yet the years since lingcod recovered have revealed just how knotty fish policy can be. No man is an island, and neither is any fish. Lingcod and its fellow bottom-dwellers are inextricably connected not only to ecological communities, but to human ones: In 2015 alone, West Coast groundfish landings were worth over $60 million, and helped support ports from Morro Bay to Puget Sound. Balancing the needs of fish, fishermen, and ecosystems is a never-ending challenge. The story of lingcod illustrates both how far fisheries management has come, and how far it has to go.

In it for the long trawl

The West Coast groundfish industry is, bar none, America’s most complex fishery. Over ninety species are caught together from California to Washington; by contrast, New England’s groundfish fishery is composed of fewer than twenty species. Fishermen use pots, longlines, and an array of net designs, and operate within a mosaic of closed areas. “You almost have to be born into the fishery to really get a handle on it,” Pettinger says.

The industry became an order of magnitude more complex in 2011, when, after years of preparatory meetings, the Pacific Council transitioned to a new regulatory scheme: a de facto private property system called catch shares. Under catch shares, West Coast trawlers received Individual Fishing Quotas (IFQs) — personal slices of the total fish pie, which they were free to trade, sell or rent to their peers. The fleet also paid for a fisheries observer — a biologist tasked with recording and reporting each vessel’s haul — on every boat. The result, says Frank Lockhart, a senior policy advisor at NOAA who helped design the system, was “individual responsibility and accountability.” Fishermen, their catches limited by quotas and meticulously documented by observers, steered clear of overfished stocks like yelloweye and canary rockfish. Bycatch fell below 5 percent. In 2014, the Marine Stewardship Council deemed 13 groundfish species, lingcod included, sustainable — the most complicated fishery the body had ever certified. “A lot of people were unsure how it was all going to work,” says Pettinger, who in 2016 won an award from President Obama for his role in championing the program. “Well, it works pretty damn well.”

To be sure, not everyone would agree. The catch share program granted 90 percent of the West Coast’s groundfish to trawlers, leaving other gear types with the scraps — a dynamic that many small-boat captains allege is fatally eroding their livelihoods. In 2015, for instance, the president of the San Francisco Community Fishing Association claimed that California’s small-boat fleet, consisting mostly of hook-and-line and trap fishermen, has shrunk by 90 percent in the last three decades, a process that catch shares has only accelerated. “That it flies in the face of sustainability to shove small-boat line fishers off the water in favor of trawl is an inconvenient fact that few people care to talk about,” wrote the author Lee Van Der Voo in her 2016 book The Fish Market.

Some trawlers have found the program challenging, too. Although many groundfish species have recovered, some rockfish continue to struggle, necessitating ongoing tight restrictions. The West Coast’s entire trawl fishery is only allowed to catch around 2,000 pounds of yelloweye rockfish per year, meaning that a single rockfish haul can put a fisherman over his personal limit. Trawlers operate in perpetual fear of “disaster tows.” After the F/V Seeker accidentally hauled up 47,000 pounds of canary rockfish in November 2015, for instance, the boat was forced to sit out the following year.

The upshot is that fishermen avoid such “choke species” like the plague. That’s good news for conservation — and, indeed, canary rockfish was declared rebuilt last year — but it can force fishermen who use unselective gear to steer clear of abundant species, including lingcod, that share reefs with rarer fish. Between 2011 and 2014, the trawl fleet caught just 16 percent of its total lingcod allocation, preventing millions of potential pounds of sustainable, local protein from being brought to market. “Operationally, the program has worked well,” says Lockhart. “But access to other stocks has been limited by overlapping species.”

With many stocks rehabilitated, West Coast managers have begun chipping away regulatory layers imposed during the bad old days of unchecked overfishing. In April 2018, the Pacific Fishery Management Council will decide how much of the West Coast’s protected habitat to open to trawling, and will also consider expanded protections based on new scientific information. That process is a testament to recovery, but it’s also fraught with ecological danger. Ben Enticknap of Oceana fears that allowing trawlers to access once-closed swaths of the ocean could have dire impacts on sensitive bottom features, including deepwater corals, sponges and rocky reefs. In recent years, mapping and remotely-operated submersibles have given scientists a better understanding of the seafloor around places like California’s Channel Islands, which Oceana explored in 2016. At one site, near Santa Barbara Island, the submersible’s lights illuminated a never-before-seen grotto of stunning gold gorgonian corals teeming with squat lobsters, octopus, and rockfish. “These are the habitats that we want to make sure are protected and not damaged in the future by any expansion of bottom trawling,” Enticknap says.

An Oceana proposal submitted in 2013 would do just that, providing new protections to over 140,000 square miles of hard rocky reef; setting off-limits places where observers have documented high bycatch of sponges and corals; and opening new areas where trawling can safely occur. At the same time, the proposal would also restore fishing access to some Rockfish Conservation Areas, resulting in a net increase in trawling opportunities. “We’ve demonstrated with science and analysis that our proposal is designed to maximize habitat protection while minimizing economic impacts to the bottom trawl fleet,” Enticknap says.

Lingcod rank among the many species that stand to benefit from Oceana’s plan, owing largely to its curious life cycle. Ophiodon elongatus may be a ravenous predator, but it’s also a surprisingly tender parent. While male lingcod often spend their entire lives patrolling a single rocky reef in the shallows, adult females prefer to hunt deep waters like those around Santa Barbara Island. Each winter, these mature females move briefly inshore to deposit eggs embedded in a viscous, yellowish paste that glues the mass to the rocks. After the males fertilize the clusters, they zealously guard the clutches for weeks, defending them from all comers until the larvae emerge. The females, meanwhile, wander back to their deep-sea feeding grounds. “There have been serious improvements in the management of the groundfish trawl fishery — ending overfishing, increasing accountability for individual fishermen, reducing bycatch,” Enticknap says. “The last big push needs to be protecting these important seafloor habitats.”

Shifting tides

In one crucial way, we stand now on the cusp of a sea change in fisheries management. For decades, biologists and regulatory councils considered fish stocks in isolation, as though fishing was the only factor that could affect a population. The single-species approach was simple enough: When stocks collapsed, managers dialed down fishing pressure; when populations rebounded, they ramped it up. That strategy, though, fails to recognize that fish stocks are members of complex ecological communities, whose health is driven not only by fishing, but by interactions with other organisms, habitat, and oceanographic conditions.

In recent years, agencies have shifted, in fits and starts, toward an ecosystem-based approach to management, one that attempts to account for the ocean’s overwhelming complexity. In 2016, NOAA took a landmark step toward that vision by prohibiting new fisheries for hundreds of species of forage fish — the small, silvery creatures, like eulachon and smelt, that feed everything from seabirds to whales — until scientists can determine that pursuing them won’t harm marine ecosystems. Oceana and other conservation groups hailed the decision — the first time, perhaps, that managers have acknowledged the spectacular intricacy of marine food webs.

To the eyes of some scientists, West Coast groundfish present a perfect test case for that nascent approach — a fishery whose dozens of constituent parts live together, eat and are eaten by one another, and are already responding to dramatic oceanic changes. “Is there a more holistic way of coming at lingcod and rockfish management?” asks Tim Essington, a marine scientist at the University of Washington. Protected zones in Washington’s state waters, Essington points out, are “just chock full of gigantic lingcod,” which may be delaying rockfish recovery via their voracious appetites. Figuring out a way to sustainably harvest lingcod without hauling up rare rockfish as bycatch, Essington, says, could provide “a potential win-win scenario.”

In 2014, a group of fishermen in Ilwaco, Washington, set out to explore just such an opportunity. The group worked with the Nature Conservancy to test a new type of fishing pot that, in theory, would trap lingcod while allowing smaller rockfish to escape. The pot didn’t work as intended — it caught more sablefish than anything else — but the innovators didn’t give up. In early 2017, the Conservancy received an Experimental Fishing Permit that will let them test an assortment of custom-built pots in otherwise closed areas. Bait choice might matter as much as pot design. While rockfish are attracted to strong-smelling bait, says Jodie Toft, a marine ecologist with the Nature Conservancy, lingcod are primarily visual predators. “If we’re lucky, it will be as simple as using flashy bait rather than stinky bait to keep the rockfish out and the lingcod in,” Toft says.

Managing West Coast groundfish in a holistic, ecosystem-based fashion will become even more important in the face of climate change. Pete Adams, the scientist who assessed lingcod populations back in the ‘90s, points out that lingcod must deposit their nests in highly oxygenated nearshore waters in order for oxygen to penetrate the dense egg masses. The problem with that strategy is that warmer waters hold less oxygen, and marine species along the West Coast are already suffering as a result. “We’re entering a new phase of ocean conditions,” Adams warns, in which old management assumptions may no longer apply.

That uncertain future makes habitat protection and cautious rebuilding all the more important, says Geoff Shester, Oceana’s California campaign director and senior scientist, so that lingcod and other groundfish remain resilient against whatever sweeping changes come their way. Against the odds, we’ve successfully recovered lingcod once. With luck, and sound ecosystem-based management, we’ll never have to do it again.