October 27, 2016

Celebrate Halloween with 3 Skin-Crawling Ocean Parasites

BY: Allison Guy

The sea is full of creatures that look like they’ve swum straight from the ninth circle of hell: Vampire squid. Goblin sharks. But few ocean animals are scarier than the smallest ones: parasites. From castration barnacles to infectious jellyfish, these three parasites prove that evolution is far freakier than any midnight double-feature.

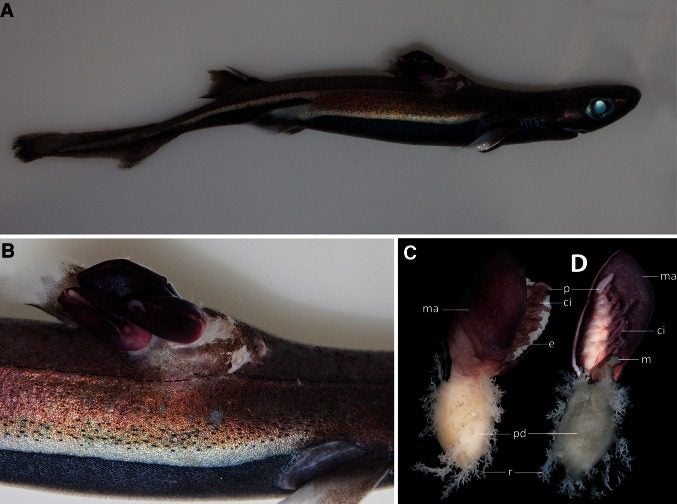

1. Anelasma squalicola: The blood-sucking, shark-castrating barnacle

Imagine a freeloader who rides in your car’s passenger seat and helps himself to everything you own. He steals your cash. He gobbles your groceries. And worse: He never leaves. Now, replace a car with your body and you have some idea how nightmarish an Anelasma squalicola infection is for itty-bitty sharks called dogfish.

Most barnacles are hard-shelled, harmless filter-feeders that anchor themselves to hard surfaces or bigger animals like whales. They use feather-like appendages called ‘cirri’ to nab plankton drifting in the water.

But Anelasma squalicola lack a hard shell. And while they have cirri, they’re underdeveloped and useless. They do sport a ‘peduncle’ — the structure that barnacles normally use to moor themselves to a solid spot — but Anelasma have transformed these anchors into nutrient-sucking straws.

Anelasma barnacles only target deep-sea dogfish sharks, and they have a special preference for velvet belly lanternsharks — so-called because their undersides are velvety black, and their bioluminescent organs light up like lanterns.

Once an Anelasma finds a suitable velvet belly, it latches on and sinks its branching, root-like peduncle into its host’s flesh, absorbing nutrients from the shark’s blood and tissues.

Apparently not content with being a literal drain, these barnacles also hamper the sexual development of their hosts. Mature male lanternsharks with a freeloading barnacle develop smaller testes than their non-parasitized brothers, while females grow fewer and smaller eggs.

If that’s enough to put you off a beach vacation, don’t throw your bathing suit away just yet. Anelasma is the only barnacle known to parasitize vertebrates. Given that plenty of other barnacle species live so close to vast supplies of nutrients — think of all the barnacle-sustaining blood in a whale — scientists are puzzled why Anelasma is the exception, not the rule.

2. Euhaplorchis californiensis: The brain parasite that makes killifish dance like no one’s watching

In the Middle Ages, outbreaks of ‘dancing plague’ in Europe drove hundreds of people to senselessly dance for days on end until exhaustion or death claimed them.

The mind-controlling parasite Euhaplorchis californiensis drives California killifish — pipsqueak minnows just 11 centimeters long — to do something similar. Infected killifish shimmy, shake and act unafraid: all conspicuous behaviors tailor-made for attracting the attention of hungry seabirds.

Parasitic Euhaplorchis flukes begin the first phase of their lives inside hornsnails dwelling in California’s bays and salt marshes. After hatching and growing inside the snail, the larvae wriggle into the water, searching for the second host they need in their three-part lifecycle: a killifish.

Once a fluke finds a killifish, it burrows into its skin and follows blood vessels or nerves to the fish’s brain. There, thousands of fluke ‘cysts’ form a blanket-like mass over the brain and release chemicals that alter their host’s balance of dopamine and serotonin.

This chemical readjustment triggers the normally cautious killifish to act as bold and footloose as a drunk uncle at a wedding.These tactics work swimmingly to pass the Euhaplorchis into their third and final host, a seabird. A zombified killifish is 10 to 30 times more likely to be snapped by a passing heron or pelican than an uninfected one.

Once inside the bird’s digestive tract the Euhaplorchis californiensis lay eggs, which the seabird unwittingly disperses in its feces. If the eggs fall into water, they may be consumed by a hornsnail — and the cycle of mind-control can start up anew.

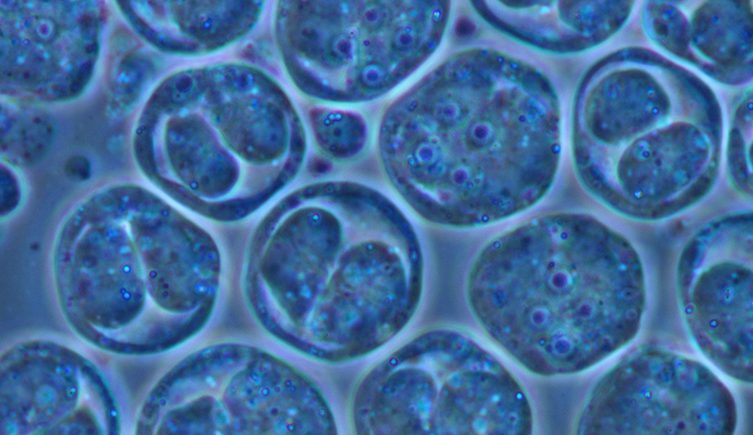

3. Myxozoans: The infectious jellyfish that live inside other animals

As if jellyfish weren’t scary enough as-is, evolution has thrown a freaky curveball with microscopic parasites dubbed ‘myxozoans.’

Myxozoans have puzzled scientists for over a century. They consist of only a few cells. They come shaped like worms, blobs or stars. And they infect animals from fish and frogs to birds and small mammals. A myxozoan infection is usually harmless, though it can trigger dangerous kidney disorders and a condition called ‘whirling disease’ in salmon and trout.

The only anatomical giveaway that myxozoans are related to jellyfish are their small, spring-loaded structures called ‘polar capsules.’ These capsules look strikingly similar to a jellyfish’s harpoon-like stinging cell.

It wasn’t until 2015 that genetic testing confirmed that the 2,200 species of myxozoan are indeed jellyfish — albeit profoundly odd ones. Their genomes, for instance, have only around 20 million base pairs, compared to over 300 million in the average jelly. And they lack the ‘hox’ genes that are essential for body development in every other animal from worms to whales.

Somewhere in the distant past, the free-swimming ancestor of modern myxozoans realized life would be much easier stealing room and board from other animals, rather than fending for itself. And that might be the most horrifying Halloween lesson from these three parasites: at least for some species, laziness is the surest path to success.