April 13, 2020

Climate change is hurting the ocean, but the ocean is fighting back

BY: Emily Nuñez

There was a time when Australia’s Great Barrier Reef was great in every sense of the word. In 1981, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) signed off on a plan to make the reef a UNESCO World Heritage Site, writing in its evaluation that the area “comprises some 2,500 individual reefs of all sizes and shapes, providing the most spectacular marine scenery on earth.”

Just 35 years later, a massive heatwave swept through the sea and wiped out more than a quarter of those spectacular corals, leaving pallid skeletons where multicolored polyps once stood. The forecast for the Great Barrier Reef’s future is equally dismal: In a recent report, the Australian government described the reef as “an icon under pressure” with a “very poor” longterm outlook.

How did one of the seven natural wonders of the world decline so quickly? Climate change, primarily. The ocean has absorbed 90% of the extra heat in our atmosphere and, consequently, it saw the hottest temperatures on record last year. Additionally, the ocean has absorbed 20 to 30% of our carbon emissions since the ‘80s, triggering chemical changes that make waters more acidic.

Combined, excess heat and increased acidity can precipitate the collapse of entire ecosystems, including the mass bleaching of coral reefs. If the planet heats up by 2°C, nearly all of the world’s coral reefs will die.

And yet, even in an increasingly hostile ocean, pockets of resilience can still be found. Across the equator from Australia, in another part of the Pacific, the corals of Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park are in comparatively good shape. Within this protected park in the Philippines, you can find snapper and sweetlips intermingling with whale sharks, tiger sharks, sea turtles, and marble rays against a kaleidoscopic backdrop of 360 different coral species.

By preserving places like Tubbataha, coral reefs can become more resilient in the face of climate change. At the same time, the ocean itself can be used as a tool for mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Ocean-based solutions could provide 21% of the emissions reductions needed to limit global warming to 1.5°C by 2050, according to a report released last year by the High Level Panel for A Sustainable Ocean Economy, a group of 14 world leaders. The only question is: How do we do it?

Oceana has answers. Using a three-pronged approach, Oceana is attacking climate change by protecting carbon-sequestering habitats, supporting sustainable fisheries, and campaigning against expanded offshore drilling. Here’s how.

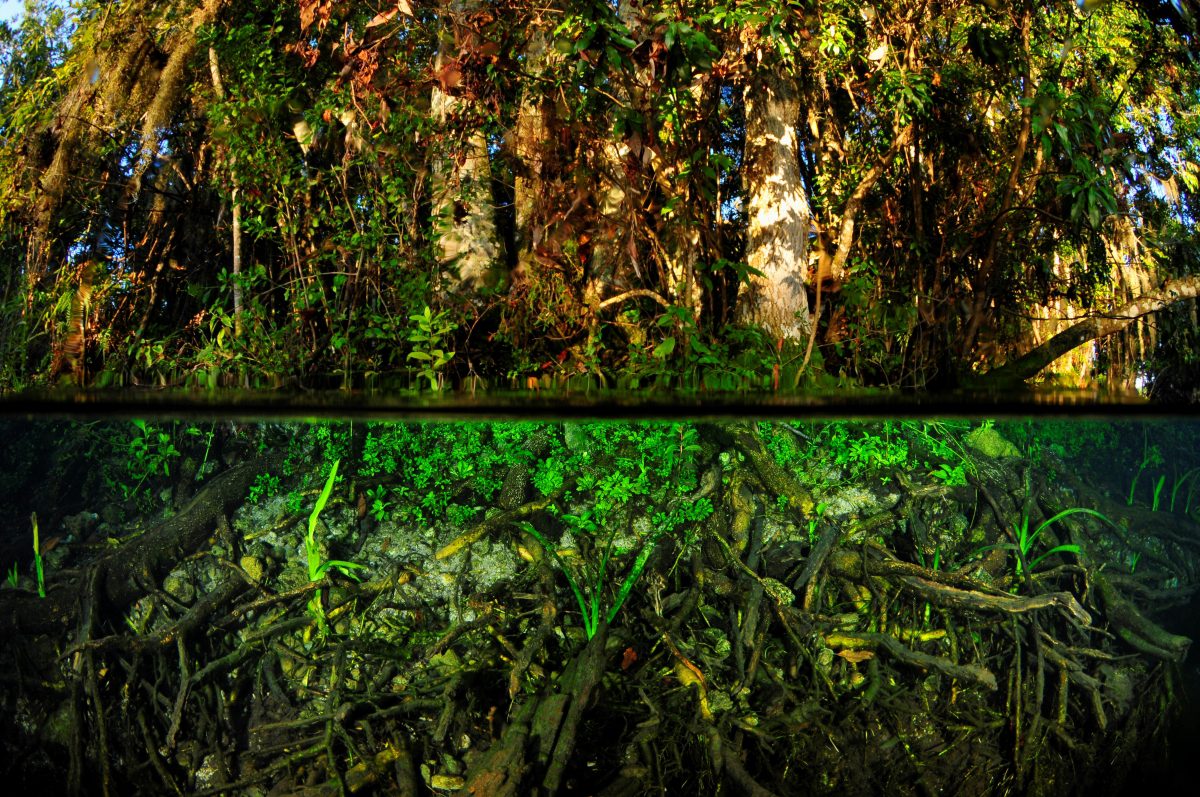

1. Oceana protects carbon-sequestering habitats like mangroves and kelp forests.

Mangroves are coastline-hugging trees that thrive in warm, shallow, salty waters. Their waxy leaves peek out above the water, but below the surface is where the magic happens. There, you’ll find a tangle of roots and, below that, a thick layer of soil capable of capturing roughly four times the amount of carbon that tropical forests store. This is because mangrove soils tend to be deeper than other forest soils, and their low levels of oxygen help store carbon more efficiently.

These trees are the true superheroes of the sea. They act as nurseries for baby fish and provide shelter to a variety of marine animals, many of which hold commercial value. They trap sediments and filter wastewater before it is discharged into the ocean. They even act as a natural shield, protecting people from the worst of the storms that have been plaguing coastal communities with greater frequency and intensity as oceans heat up.

“Communities with more extensive mangrove forests experience significantly lower losses from exposure to cyclones than communities without mangroves,” the High Level Panel concluded in its report.

Mangroves are strong, but they aren’t invincible. It’s estimated that up to half of the world’s “blue carbon ecosystems” – a category that includes mangrove forests, salt marshes, and seagrass beds – have been degraded or converted into other applications, like carbon-intensive shrimp farms or rice fields.

In the Philippines’ Manila Bay, the devastation has been far greater; nearly 99% of the mangroves in this area have been decimated since the beginning of the 20th century. Mangroves store carbon that may have built up over hundreds or even thousands of years, and yet, when they’re destroyed, it takes mere decades for greenhouse gases to seep back out into the environment.

To protect what’s left of the Manila Bay mangroves, Oceana is campaigning to prevent a development project that would mow down hundreds of mangroves and convert part of the bay into land. San Miguel Corporation – the largest company in the Philippines by revenue – wants to build an airport in Bulacan province, just outside of Manila. This development, called the New Manila International Airport, would displace hundreds of coastal families and cause irreparable damage to habitats, fisheries, and the livelihoods of local artisanal fishers.

Oceana’s team in the Philippines is building a groundswell of opposition to the project by collaborating with local allies and scientists that want to protect Manila Bay. Oceana has also launched an online petition to stop land reclamation along the coast. These “dump-and-fill” infrastructure projects threaten marine biodiversity and disturb fragile coastal ecosystems.

Like mangroves, seaweeds like kelp also sequester carbon. As a partner of Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Vibrant Oceans Initiative, Oceana is working in Chile to stop the overexploitation of brown kelp, a type of seaweed that’s typically used in food additives and cosmetics. As the largest artisanal “fishery” in Chile, kelp supports thousands of jobs, but the industry could come crashing down if extraction continues at current unsustainable rates.

Oceana’s goal is to get the Undersecretary of Fisheries to adopt a management plan by 2023 that keeps kelp extraction within healthy levels. This will help preserve harvesters’ jobs in the long-term while also keeping more kelp in the ocean, allowing the algae – and the carbon it sequesters – to naturally sink to the seafloor.

2. Oceana supports sustainable fisheries that yield low-carbon seafood.

In the context of climate change, science-based fisheries management is more vital than ever. Warming waters are creating a refugee crisis in the ocean, causing fish to go where they normally wouldn’t. At times, when commercially important species have crossed geopolitical boundaries, “fish wars” have been fought over who owns the rights to these resources.

Tropical fish from the Caribbean have been spotted off the U.S. coast of Georgia. Blue whiting from Iceland are increasingly popping up closer to Greenland. And zooplankton – a major food source for many sea creatures – have been shifting poleward by at least 40 kilometers per decade since the mid-1800s.

“Temperature is one of the most pervasive factors affecting a wide range of species all around the world,” said Oceana Science Advisor Dr. Malin Pinsky.

He added, “Warming makes it harder, in effect, for fish and other marine animals to breathe. As temperatures go up, their metabolism and heart rate goes up, and they demand more oxygen.”

To make matters worse, warming waters are compounded by other problems like pollution, overfishing, habitat loss, and higher acidity and lower oxygen levels in the water. When oxygen and food are limited, heat can stunt the growth of fish and make them less resilient.

There’s a link between sustainable fisheries and climate change adaptation: By campaigning to reduce overfishing, Oceana is helping marine life withstand a harsher environment.

“Overfished species are particularly vulnerable to climate change,” Pinsky explained. “Reducing overfishing and giving species a chance to recover may be our best chance of ensuring that fisheries are still viable in the future.”

In addition to supporting sustainable fisheries management, Oceana endorses the Paris Agreement, which has the potential to protect 3.3 million metric tons of ocean catch – more than the average annual catch of Norway – as well as $4.6 billion in fishing revenue, according to a study led by Oceana Board Member Dr. Rashid Sumaila.

Oceana is also working to end bottom trawling, the most fuel-intensive and destructive fishing method that exists. To date, Oceana has protected millions of square kilometers of ocean habitat from this harmful type of fishing.

As an added benefit, the safer and more sustainable a fishery is, the more ethically a low-carbon source of protein can be provided to a growing global population. Compared with other sources of protein, like beef and pork, most seafoods have a significantly lower environmental impact.

“In comparison to land-based agriculture, wild fisheries produce a modest amount of greenhouse gases and require virtually no freshwater or arable land,” Alexandra Cousteau, senior advisor to Oceana, said while addressing government officials, business leaders, and scientists at the Our Ocean conference in Norway last fall.

“At Oceana, we know that if we rebuild ocean abundance, we can feed the world.”

3. Oceana campaigns against expanded offshore oil and gas drilling.

It’s no secret that offshore drilling takes a toll on the environment. It’s a sizable contributor to carbon dioxide emissions, and an underreported generator of methane, a powerful greenhouse gas.

Not to mention, there’s the constant threat of oil well blowouts. An Oceana report showed that at least 6,500 oil spills occurred in U.S. waters between 2007 and 2017, but despite their frequency, clean-up methods are generally ineffective and have remained largely unchanged since the late 1980s. This means that oceans and marine wildlife are no safer than they were when BP’s Deepwater Horizon rig exploded, unleashing the worst environmental disaster in U.S. history.

Belize recognized the seriousness of these dangers. In December 2017, following years of campaigning by Oceana, the country made history by passing an indefinite moratorium on offshore drilling in national waters. This secures greater protections for the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef – a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the second largest reef in the world, after Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

This was an enormous victory for Oceana and Belize. However, the threat of offshore drilling looms elsewhere in the world, including the U.S., where President Donald Trump announced plans to open nearly all federal waters to oil and gas development. If the President’s plan moves ahead, the fallout would be disastrous: An additional 46 billion metric tons of greenhouse gas emissions would be discharged into the atmosphere, according to an assessment by the Center for American Progress (CAP).

“Put another way, such an increase is the equivalent of the yearly emissions from nearly 10 billion cars – nine times as many cars as are on the road worldwide today,” CAP wrote.

Last April, the state of New York issued a loud and clear rebuke to that plan when Governor Andrew Cuomo signed a bill to prohibit offshore oil drilling and associated infrastructure in state waters. Cuomo isn’t the only one taking a stand, either. Nine states have laws on the books against offshore drilling, and every East and West Coast governor – including Democrats and Republicans alike – has opposed expanded offshore drilling along their coasts.

“If we are to avert the worst impacts of climate change, we cannot afford open season for oil drilling on our oceans,” said Diane Hoskins, campaign director at Oceana. “Along the coast, citizens, businesses, and elected officials are united in opposition to offshore drilling, including over 380 communities that have passed formal resolutions.”

Until President Trump’s offshore drilling plan is completely revoked, Oceana will continue to campaign against it to prevent the damage before it’s done.

The future of coral reefs is in our hands.

In the Philippines, where 90% of surveyed corals range in condition from poor to fair, the colorful corals of Tubbataha Reef are faring better. This may come as a surprise, considering that the reef and its residents suffered the effects of “blast fishing,” a destructive, dynamite-detonating method that kills everything within a 30- to 100- foot radius (9 to 30 meters). In the 1980s, at the height of blast fishing in the region, the seafloor was left scarred and coral reefs were reduced to rubble.

But the reef managed to make an impressive comeback, thanks to the area being declared a no-take zone in 1995. With time, several fish populations recovered, causing a “spillover effect” into areas outside of the reserve, where fishing is permitted. In turn, both the fishers and the fish benefited.

While Tubbataha is now well protected, other areas in the Philippines are still vulnerable to future harm. That’s why Oceana, with the support of Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Vibrant Oceans Initiative, is looking to establish a marine protected area (MPA) in a coral-rich region of the Philippines within the next few years. By protecting the diverse array of corals and fish that live in healthy reefs, the damage caused by global warming and other stressors can be lessened.

In some cases, carefully designed MPAs can help corals evolve to withstand higher temperatures over time, according to other research led by Timothy Walsworth at the University of Washington and coauthored by Pinsky.

“Corals are facing a gauntlet over the coming years and decades from warming oceans, but we found that reef conservation in general can really boost corals’ ability to evolve and cope with these changes,” Pinsky said.

“There is strength in diversity, even when it comes to corals. We need to think not only about saving the cooler places, where corals can best survive in the future, but also the hot places that already have heat-resistant corals. It’s about protecting a diversity of habitats, which scientists hadn’t fully appreciated before.”

The Great Barrier Reef is a cautionary tale of the harm that climate change can inflict, but the story doesn’t have to end there. This latest research paints a picture of what marine ecosystems can look like when we act to preserve habitats, restore abundance, and inject some color and life back into our oceans. Together, we can tell that story and give the ocean the happy ending it deserves.

This story appears in the current issue of Oceana Magazine. Read it online here.