August 14, 2017

Daniel Pauly and George Monbiot in conversation about “shifting baselines syndrome”

BY: Allison Guy

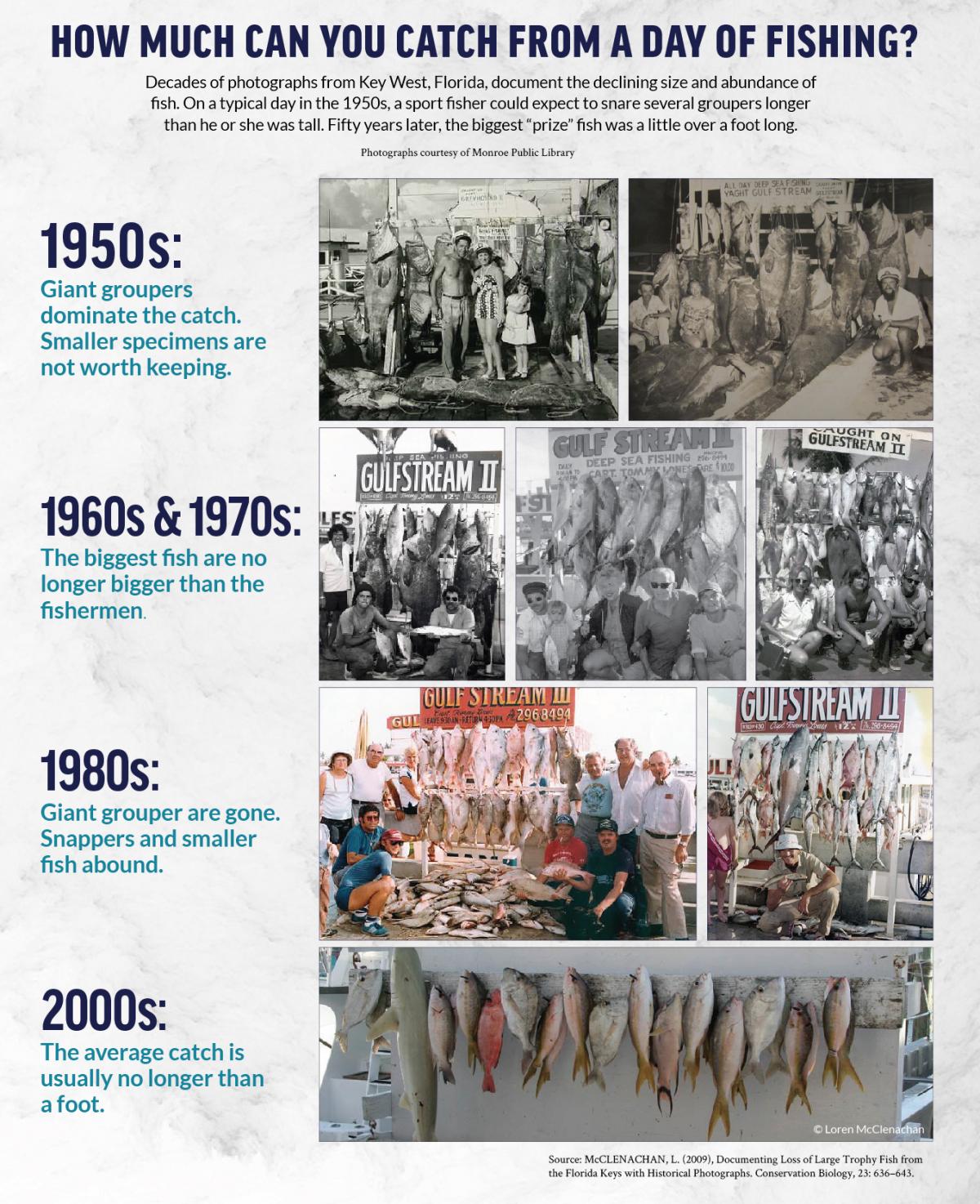

Why is it that a young fisherman views his catch of a few scrawny sardines as natural, while an old-timer sees it as the sad scraps of an ocean once brimming with giant wildlife? Two decades ago, renowned fisheries expert Daniel Pauly introduced “shifting baselines syndrome” to explain our generational blindness to environmental destruction. In recent years the idea has found a particular advocate in George Monbiot, a respected environmental writer. Oceana spoke with Monbiot and Pauly to learn how much we’ve lost, and what it will take to make abundance the ocean’s new baseline.

Oceana: How did “shifting baselines” get its start?

Pauly: In 1995, I got an email from the editor of Trends in Ecology and Evolution asking me if I could help out. Somebody had failed to deliver a one-page script. They wanted an essay, anything, to fill in the space. I quickly wrote this thing based on what was floating in my head at the time.

Oceana: Since then, why has “shifting baselines” gained traction in so many disciplines?

Monbiot: It’s incredibly useful both in the immediate sense, in that it explains our attitudes to ecosystems and our failure to perceive the way in which they’ve changed, but also as an analogy, a metaphor, a homology for stuff that’s going on elsewhere. I’ve used it in the political sense to say: Why do people accept tyranny and despotism and the erosion of democracy? It’s because you normalize whatever surrounds you.

Shifting baselines has helped me to greatly understand the problem in my home country, the U.K. Conservation in this country has become indistinguishable from destruction, because what we’re conserving is an ecocidal system of sheep ranching. Sheep eat everything, and as a result there’s no birds, no insects. We’ve lost almost everything, and yet we regard that as normal and natural. This is a tremendous example of shifting baseline syndrome.

Pauly: I would like to make a point about what George just said. It is an anecdote about the shifting baseline syndrome, and anecdotes are important. If you want to fight the loss of memory and knowledge about the past, you have to rely on past information. But past information is viewed by many fisheries scientists as anecdotal. There is no knowledge in the past, however secure, however sound, that they are willing to consider because it is not couched in the verbiage that is currently fashionable.

In other disciplines, for example astronomy, they will use the position of a star or an eclipse that was found in old documents in Sumerian or in Chinese. But fishery scientists would not accept a record of a fish that was bigger than at present, or a record of abundance that is not compatible with the present. They will say these are anecdotes; we cannot use that. But these are data. We have to get rid of this notion that the past is a provider of anecdotes and the present is a provider of knowledge.

Oceana: How have you see shifting baselines syndrome play out in your own research?

Pauly: My catch reconstruction project indicates that the world’s fish catch is bigger than reported — in hindsight, that’s almost obvious. In the process we discovered another kind of bias that I was not aware of: I would call it the “presentist bias.” When the UN Food and Agriculture Organization records global fish catch, it corrects for missing data in the present, but not in the past. And so we have the impression that everything is fine, while in fact the catches that we extract from the sea are in free fall.

Monbiot: There’s a classic example of that here in the North Sea, where the baseline is 1970. And they say: Look, we’re doing great because we’re almost back up to the natural condition of stocks. But by 1970 there had been over a hundred years of mechanized fishing, which had been absolutely devastating.

Pauly: This is also the case for the U.S. The U.S. requires that stocks be rebuilt, but they usually use the ‘80s as a baseline. But in the ‘80s there were huge foreign fishing fleets along the U.S. coastline. Stocks were overexploited. Some had collapsed. To use the ‘80s as a rebuilding goal is completely ludicrous if you think about it.

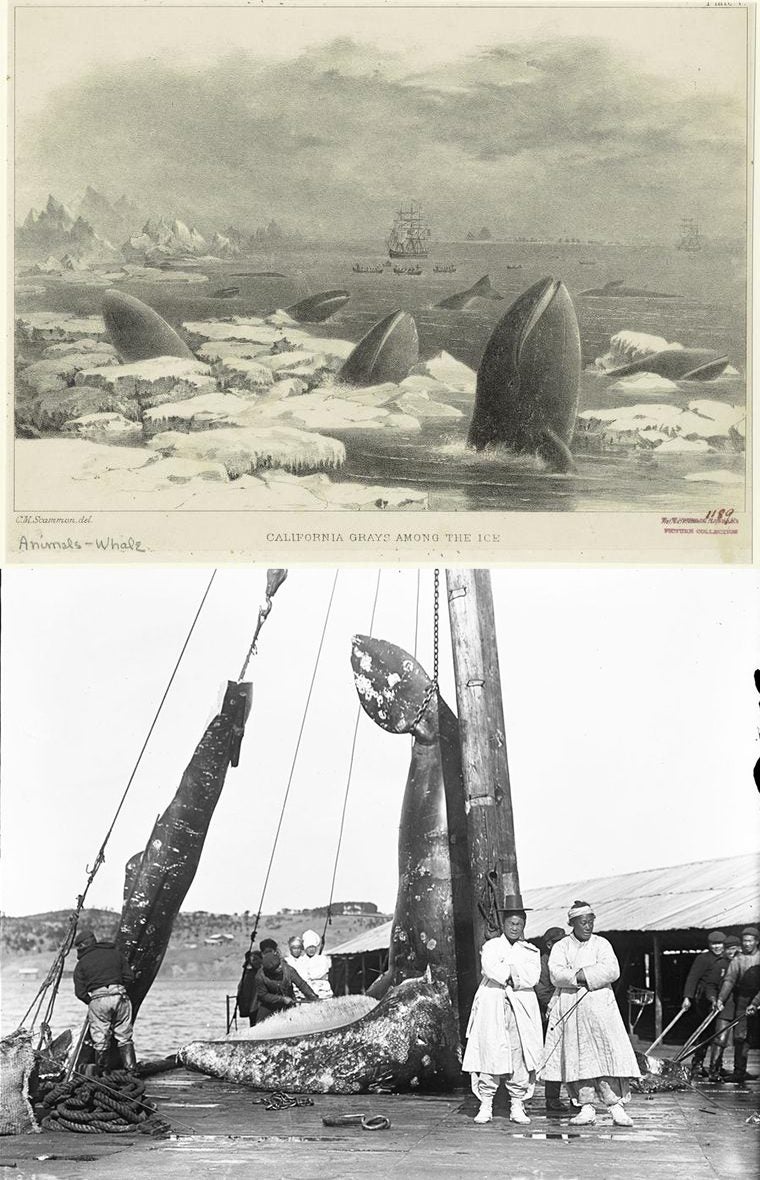

Monbiot: What I think is so often missed is that the natural world, in its natural state, is a system of almost unbelievable abundance. Almost all ecosystems everywhere on earth, on land and at sea, were once dominated by enormous animals. Whales were everywhere, great sharks were everywhere. If you go back to the last interglacial period, Britain was dominated by the straight-tusked elephant, a beast so massive that it makes the African elephant look like a ballet dancer.

Oceana: Can we restore ecosystems to this ancient state of abundance?

Pauly: I don’t think it’s likely that we can restore pre-contact, pre-human ecosystems. As soon as humans appear on the scene the large megafauna is annihilated, no matter if it is in Australia or North America. So, these animals are toast regardless. But we started the industrial age, in fisheries at least, as late as 1880. 1880 is an important date because it’s the first time we used fossil energy to go after fish. That’s when the first trawler was deployed around England. Even then, there was still a huge megafauna in the sea.

Industrialization, at least in Europe and in Russia, is well-documented. We don’t know about marine ecosystems 10,000, 20,000 years ago. But we sure know about 120 years ago. I think these are politically defensible reconstructions of biomass that one can push. We should use these reconstructions at least as aspirational goals.

Monbiot: My only concern with that is when you read the accounts of the first European arrivals on the eastern seaboard of North America they encountered extraordinary marine life — these vast lobsters just there for the taking in the rock pools, these huge shoals of sturgeon moving up the rivers. If you go back far enough in Britain, it’s the same thing.

Pauly: I’m just being pragmatic about it. For my catch reconstruction project I chose to start in 1950, because industrial countries had just been through WWII, and most other countries had not yet begun to industrialize their fisheries. This gives a nice contrast. But ultimately, it will always be an arbitrary decision.

Oceana: So, is it enough to choose a set point in the past and aim for that?

Monbiot: I would say that recognizing a baseline is itself not a policy, but it is something which can inform. We can use our understanding of paleoecology to guide us how far we can go towards that ideal. And in marine ecosystems, there is a very good compromise that can be struck, which is to create large marine reserves in which no commercial extractive activity takes place. It’s one of those rare situations where large-scale conservation of resources is going to benefit everyone, even in the short term. It’s a genuine win-win.

Take sea angling here in the UK. Even with our greatly depleted seas, and even though angling is a pretty dispiriting experience because there’s so little to catch, it still brings in more income and employs more people than commercial fishing activities. It generates loads of economic activity that stays in the community: the bed and breakfasts, the cafes, the tackle shops. And on top of that you’ve got all the other things that you get from a pristine marine environment. You’ve got the dolphin watching, you’ve got the snorkeling and the diving.

Pauly: In British Columbia, there was a whaling industry that operated from shore stations until the ‘60s. They killed all the humpback and gray whales that were there. But now we have a whale-watching industry that makes more money than the whaling industry ever made. We even have Japanese tourists coming to see our whales! And the benefits are spread all along the coast, whereas before they only went into the pockets of the owners of the whaling industry. If you were to rewild Britain and other places, you would have all kind of tourist-based economies that now don’t exist.

Oceana: If we manage to restore or “rewild” the ocean, what do we gain beyond economic benefits?

Pauly: The system becomes more resilient to change. That will be important with global warming intensifying. If there are more animals, there are more interactions, and it’s the long-term stability of this interaction that prevents rapid change from happening.

To pick an example, in Tasmania, Australia, there is an invasion of sea urchins from the Sydney, in the north, because marine animals are moving towards the poles. These sea urchins eat all the kelp. But if the kelp-eating sea urchins arrive in an intact marine reserve, they get eaten by the large fish, and the kelp is still standing. Whereas in areas where there are no large fish the sea urchins can eat the kelp and devastate the entire ecosystem.

Oceana: Are there any emotional or spiritual gains from a rewilded ocean?

Monbiot: Wonder, enchantment, a discovery of hidden aspects of ourselves, insight into living processes of the kind that is impossible in managed and degraded ecosystems, and the knowledge that we are not the only species to benefit from this transition.

But above all it gives us something even more endangered than Patagonian toothfish: hope. A positive environmental vision, with rewilding at its heart, is an essential antidote to the endless stream of depressing news about what’s happening to the living world.

Daniel Pauly

Dr. Daniel Pauly is one of the most prolific and widely cited fisheries biologists in the world. Born in France and raised in Switzerland, Daniel Pauly acquired a doctorate in fisheries biology in 1979 from the University of Kiel. After working in the Philippines through the 1980s and early 1990s, Pauly became a professor at the University of British Columbia Fisheries Centre in 1994, and was its director from 2003 to 2008. In 1999, Pauly founded, and since leads, Sea Around Us, a large research project devoted to identifying and quantifying global fisheries trends. He is the author or co-author of over 1,000 articles, books and book chapters on fish and fisheries.

George Monbiot

George Monbiot studied zoology at Oxford and has spent his career as a journalist and environmentalist. His celebrated Guardian columns are syndicated all over the world. He is the author of the bestselling books Captive State, The Age of Consent, Bring on the Apocalypse and Heat, as well as the investigative travel books Poisoned Arrows, Amazon Watershed and No Man’s Land. His 2014 book, Feral: Rewilding the Land, the Sea, and Human Life, won the Orion Book Award, the Society of Biology Book Award and the Zoological Society of London’s Thomson Reuters Award. He has won is the United Nations Global 500 award for outstanding environmental achievement, presented to him by Nelson Mandela. His most recent project is a concept album, written with the musician Ewan McLennan, called Breaking the Spell of Loneliness.