February 1, 2024

Defending the Humboldt Archipelago

BY: Sarah Holcomb

When Tania Rheinen first visited the coast along La Higuera on a typical cool, clouded morning in 2017, the white sand and cerulean water reminded her of Chile’s many other picturesque beaches. “Nothing too special,” she thought. Aboard a local fisher’s boat, however, she changed her mind. “Suddenly, there were seven or so bottlenose dolphins jumping around the boat,” remembers Rheinen, who had joined Oceana as its communications director in Chile a year earlier. A family of fin whales swam by. “By that time, I was in awe.”

La Higuera is a region that belongs to the Humboldt Archipelago, where around 80% of the world’s Humboldt penguins reside, kelp forests tower like underwater castles, vast numbers of sea birds soar, and abalone and razor clams verge on endless. Before the chalky desert road to La Higuera was paved, scientific researchers and students were already trekking to document the area’s biodiversity in 2008.

Coal developers were eyeing the desert oasis, too. La Higuera falls in Chile’s “Zone 4,” a swath of the country destined for mining since the 1960s. Over the next 15 years, other developers would line up, most notably the mining company Andes Iron, which introduced its $2.5 billion plan, the Dominga port mining project, in 2013.

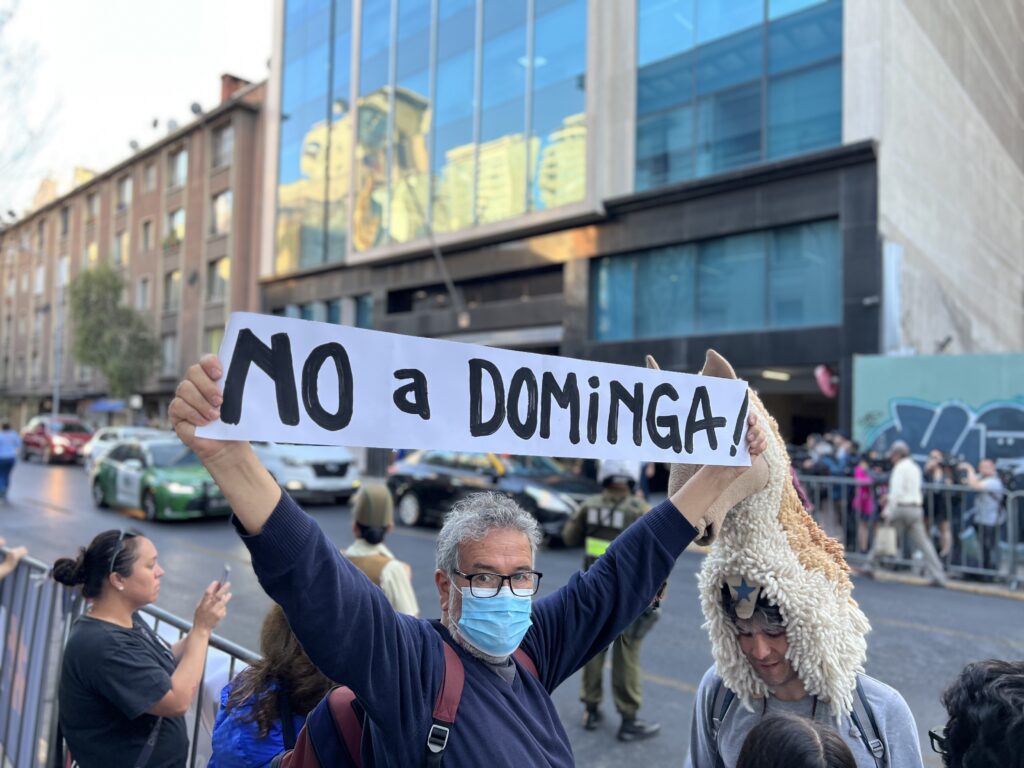

A group of nine fishers and locals living in La Higuera, who would be joined by Rheinen and her colleagues including legal and policy experts at Oceana, set out to protect the Humboldt Archipelago, turning the threats facing their coastal towns to a conversation heard around Chile: “¡No A Dominga!”

© Oceana/Jose Gerstle

Magic in the water

When 48-year-old Gabriel Molina began pioneering the effort to protect the Humboldt Archipelago, he didn’t have quite so many gray hairs.

Molina grew up in Vallenar, a city in Chile’s Atacama region north of the Humboldt Archipelago. A strong swimmer by age four, Molina loved diving to experience the wonder of swimming among fish and socializing with manta rays and dolphins. And he felt a deep connection with the water itself.

Locals aren’t the only ones who sense a certain magic in these waters. Scientists discovered the Humboldt Archipelago is the site of an “upwelling,” where ocean currents thrust cool, nutrient-rich water from the ocean depths up toward the surface. The Humboldt Current, as it’s called, animates one of the most productive ecosystems in the world. The cold waters make it possible for Humboldt penguins to live on the equator year-round. Abundant food sources attract bottlenose dolphins and blue whales close to the coast. Oceana’s scientists and photographers documented the phenomenon close-up, gathering evidence through four expeditions to protect the Archipelago’s abundant marine life.

Researchers have argued that the Archipelago needs greater protection, especially given that Humboldt penguins tend to travel, foraging up to 90 kilometers (56 miles) away from their colony. The penguins are also sensitive to human presence — scientists found that even one person passing by at a distance significantly speeds up their heart rate.

Industrial pollution threatens to turn this famous fountain of biodiversity into a so-called sacrifice zone. The Dominga project promised sprawling mines that would carve out the desert, a desalination plant that could leak toxic brine into nearshore waters, and a commercial port that would surge industrial ship activity. Once one mining project arrives, others follow, says Dr. Liesbeth van der Meer, Oceana’s Senior Vice President for Chile. “And it’s not only the place that is sacrificed,” she says, “but also the people.”

As these threats emerged, folks in Punta de Choros and other towns in La Higuera began organizing. They successfully fended off the first coal mining proposal in 2010. Nine of them, including Molina, fellow fisher Rodrigo Flores, and tourism entrepreneur Rosa Rojas, founded the Movement in Defense of the Environment (MODEMA). Their goal: create a marine protected area (MPA) to definitively protect their home from future threats.

The initiative to protect the Archipelago “didn’t come from outside, but from the fishermen and those in the business of tourism, camping, diving centers, restaurants,” emphasizes Tamara Gaymer, the current president of MODEMA. “All the people who live here realized that it was super important to protect this area, because their jobs depend on it.”

But the road ahead was full of division — not just external threats, but conflict within La Higuera itself. The new MPA could affect fishers’ activities, bubbling up local concerns among some. Mounting pressure from Dominga tangled the plot. Some community members accepted payments to side with the company, tearing at relationships between neighbors and families.

As years wore on, the core movement stayed steady. “Anytime we campaign for an MPA, it’s somewhere where people are strong enough and convinced enough that they want to do this,” says van der Meer. While community activists worked to win over their neighbors, the war against mining the Humboldt Archipelago was waging in the courts and the court of public opinion — and Oceana was in the middle of it.

From local to national

Three years after proposing the Dominga port mining project, Andes Iron unveiled its evaluation of the project’s environmental impact on the Humboldt Archipelago. And Oceana found some suspicious omissions.

Andes Iron didn’t mention how a flood of cargo ships would affect the National Humboldt Penguin Reserve or whales’ feeding grounds, for example, and the project’s mitigation measures were lacking. Moreover, the evaluation contained a slew of legal flaws. In October 2016, Oceana compiled an 80-page report explaining the shortfalls.

The report was “very technical,” recalls Rheinen. Determined to push the findings into the public eye, Rheinen and her team decided to launch a national communications strategy —NoADominga (“No to Dominga”), writing up talking points, a press release, and media pitches.

The campaign had all the right ingredients to win press attention, as Rheinen saw it: sympathetic heroes, a powerful enemy, and impending environmental peril.

Soon a well-known TV journalist made the case against the Dominga port mining project to an audience of thousands across Chile. A few months later, another journalist began investigating Dominga and published a front-page story that revealed Chile’s former president Sebastián Piñera’s close ties to Andes Iron. Within hours of the article’s debut, #NoADominga was trending across social media.

“At the beginning, nobody knew about this,” says Rheinen, “now everybody knows.”

In January 2023, community members from La Higuera, including Catalina Paz (left) from the village of El Llano de los Choros, traveled to Santiago to protest outside the Ministry of the Environment and celebrated when the Dominga port mining project was rejected.

Rejected…or not?

Meanwhile, the Dominga project continued going through rounds of bureaucratic approvals and rejections. To advocates, each round felt like a football match. And, in a clenching series of “upsets” the project was rejected at each turn.

“It was a huge shock,” van der Meer reflected afterwards.

“Mining is the motor of Chile’s economy. We have never before rejected a project, mining or otherwise, on environmental principles.” The day of the rejection in 2017, a spontaneous march celebrated the decision in La Serena, the capital of Coquimbo, drawing over 900 fishers and supporters.

Still, Andes Iron’s proposal kept coming back to life. In 2021, the government of President Piñera, in its second term, successfully appealed Dominga’s rejection, putting the project back on the table. Again, Oceana and its allies mobilized, and in January 2023 the Ministers Committee considered the Dominga port mining project once more. Their decision: a unanimous rejection.

As Andes Iron and activists continued sparring in court, organizers from La Higuera traveled to Santiago to testify on behalf of their community. But to stop the reject-and-appeal cycle, La Higuera needed to be permanently protected. With the latest appeal successfully stamped out, the window to act was now. Back in La Higuera, Molina, Gaymer, and their allies were bringing fishers from across the region together to safeguard the Humboldt Archipelago for good.

An MPA is born

Creating a marine protected area requires consensus — lots of it. Even after securing support for protecting the Archipelago, many questions remained on the table. How large should the MPA be? Where are its boundaries drawn? Will fishing still be allowed, and if so, what kinds of fishing?

After bouts of back-and-forth, fishers in La Higuera sat down with officials from Chile’s Ministry of the Environment to hash out a proposal for the Humboldt Archipelago’s protection, bringing to bear their knowledge of the ocean and local fisheries. “We educated ourselves to understand how ecosystems work,” Molina says, “learning

the relationships of the smallest organisms to the largest whale in order to better protect [the Archipelago].”

Establishing an MPA — more specifically, a kind of MPA called a “multi-use marine coastal protected area” — would prohibit any activities that impact “objects of conservation,” says van der Meer. Those objects of conservation include more than 120 local species in need of protection, among them the world’s largest population of Humboldt penguins.

This mixed-use protected area, slated to cover more than 5,700 square kilometers (2,200 square miles) between Chile’s Atacama and Coquimbo regions, would keep the harmful mines and mega-ports out while encouraging sustainable, artisanal fishing and responsible tourism to continue.

In August 2023, the MPA was approved by the Council of Ministers for Sustainability in Chile — a hard-won victory a decade in the making.

People make it permanent

Four different governments assumed power in Chile since conservationists and fishers began pushing to protect the Humboldt Archipelago. And in those 13 years, public support was building into a cultural tidal wave.

Arguably the most climactic moment arrived when Chile’s current president Gabriel Boric exclaimed “¡No A Dominga!” in his first presidential speech in 2022 to millions of Chileans. “That’s when we knew we did it,” Rheinen says.

Still, the story isn’t over. “To think that wins are forever and permanent is very naive,” says van der Meer. Since the project’s proposal predated the MPA, Andes Iron could be granted a concession, she explains. But such a scenario is looking unlikely. “Once you build the power and the people to defeat these big projects, that’s what makes [change] permanent.”

“I look at myself in the mirror and my head is white. I have been threatened with death for defending this territory many times,” says Molina. Working to protect the Archipelago is a “long, beautiful, tiring job,” Gaymer explains. “But it bore final fruit and that has kept us going. When you participate in an organization with a common goal, even if people have big differences, they manage to agree on the same objective. That has tremendous power.”

“We’ve grown as people. We have educated ourselves and that has allowed us to appreciate even more the place we have,” Molina reflects. “Not all the gold, nor all the diamonds in the world can compare with this place.”