April 28, 2016

Facing a Murky Political Future, Peru Races to Protect a Unique Tropical Sea

BY: Allison Guy

On the northernmost coastline of Peru, a mixture of cold and warm currents gives rise to a rich, biologically unique area where sea turtles swim with fur seals and penguins hunt near vivid reefs. The waters off the coast of Piura and Tumbes support 70 percent of Peru’s marine biodiversity, and supply the majority of the seafood that’s eaten within the country.

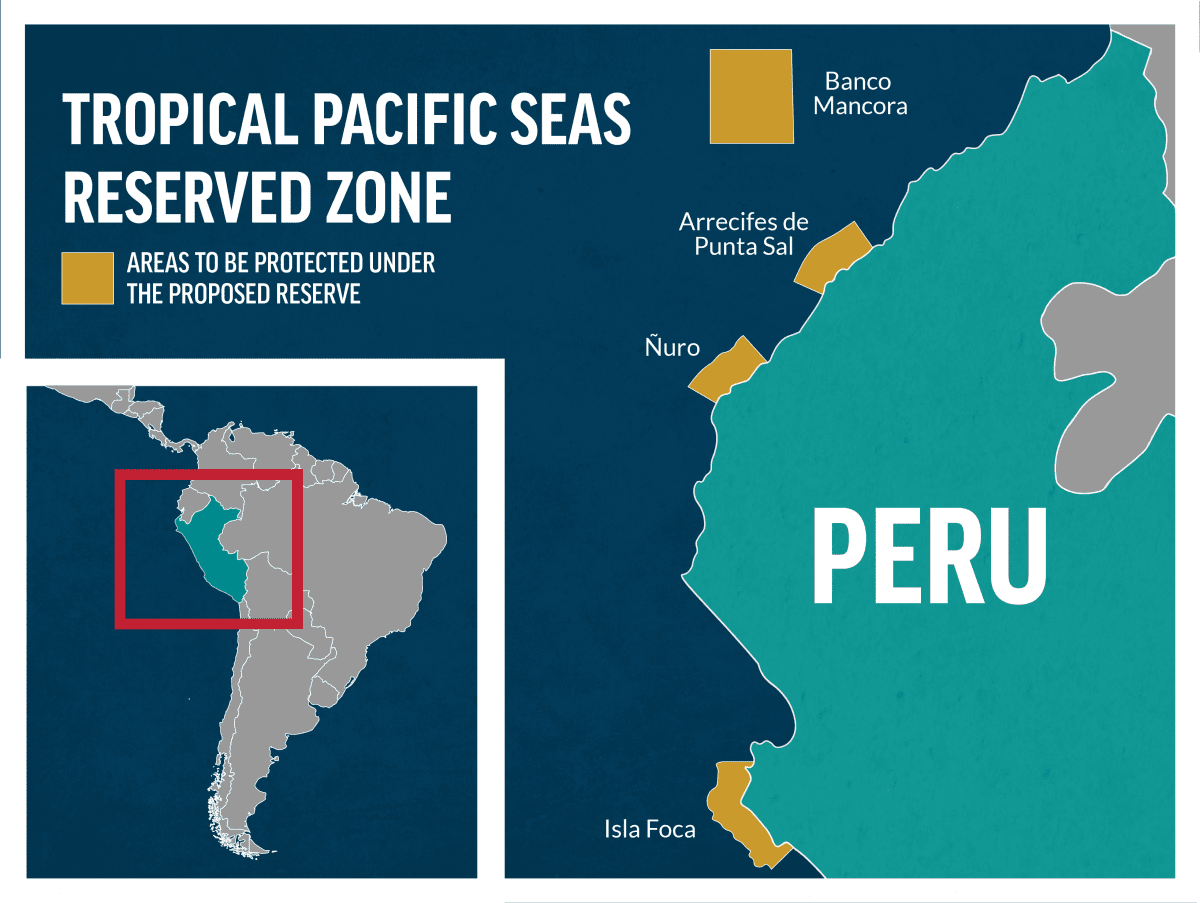

The region and its fishing communities face many threats: overfishing, pirate fishing, oil development and an uncertain political climate. A diverse coalition is hoping to fix this by making a last-ditch effort to protect Peru’s tropical seas before a new administration takes power in July. The proposed Pacific Tropical Seas Reserved Zone would host four marine areas around Foca Island, El Ñuro, Punta Sal and Máncora Bank.

The rocky islands and underwater canyons along the coast are a highway for migrating humpback whales and a permanent home to raucous colonies of endangered Peruvian pelicans and Humboldt penguins. The sandy cove of El Ñuro has a resident population of endangered green sea turtles, making it a popular tourist spot.

Scientists suspect that the rocky reef off Punta Sal may be home to undiscovered species found nowhere else on earth. The Tropical Pacific Seas Reserved Zone would also be the first marine park in Peru to include a seamount, the Máncora Bank. Due to their complex topography, these underwater mountains often support vibrant communities of marine life.

These four areas may soon become a “reserved zone” totaling 116,000 hectares. In Peru, a reserved zone is a placeholder that confers safeguards in line with the area’s conservation goals but no permanent protections. Only fully protected areas such as parks and sanctuaries are immune from changing political tides.

Patricia Majluf, director of Oceana’s Peru office, said that the “real fight” begins once a reserved zone is created. She explained that it can take years of debate for the government to transition a temporary zone into a permanent legal category.

The creation of the Tropical Pacific Seas Reserved Zone is backed by a big network of advocates. Peru’s Ministry of the Environment, tens of thousands of Peruvian citizens, international nonprofits and even American senators are pushing Peru’s current administration to finalize the designation of these areas as a reserved zone.

The creation of the Tropical Pacific Seas Reserved Zone is backed by a big network of advocates. Peru’s Ministry of the Environment, tens of thousands of Peruvian citizens, international nonprofits and even American senators are pushing Peru’s current administration to finalize the designation of these areas as a reserved zone.

The proposal, drafted by the Ministry of the Environment, is poised to be reviewed by the Cabinet of Ministers. When and if the 18 ministers come to consensus, President Humala will sign the proposal.

So far, other ministries have been in broad agreement over the creation of the reserved zone — with the exception of the Ministry of Energy and Mining. Its officials claim that the proposal is “unviable,” said Majluf. “But they refuse to say why it is.”

Majluf explained that the Ministry of Energy and Mining’s position is likely a reflection of the oil industry’s vocal opposition to the reserve. The proposed marine park overlaps or abuts 11 lots granted to eight hydrocarbon companies.

Company and industry representatives have argued that the reserve will increase the cost of doing business, or will stop potential investments dead in their tracks. They have pointed to two cases in Peru where community opposition halted projects on protected land in the Peruvian Amazon. But as the National Service of Natural Protected Areas (SERNANP) indicated, these forest projects involved legal circumstances that differ from the lots in and around the marine reserve.

Manuel Pulgar-Vidal, the Minster of the Environment, believes that oil companies are opposing the reserve as a delaying tactic. With crude oil prices at an unfavorable low, none of the companies have explored for oil or begun drilling in any of the 11 lots they’ve been granted.

These companies are nearing state-set deadlines to begin investing in oil and gas projects in these areas. If they fall behind, they may lose their leases or face hefty government fines. By framing the protected area as the reason for their setbacks, the minister said in El Comercio, they buy extra time with no risk of penalty.

Majluf suspects that the oil industry also fears increased surveillance and accountability in the event of a disaster like an oil spill. “With or without the reserve they should be keeping to the highest standards,” said Majluf. “What they’re saying is, ‘we don’t want this because we don’t want to behave.’”

Majluf and other advocates for the reserve hope that the Minister of the Environment and the Minister of Energy and Mining can resolve the dispute over the Tropical Pacific Seas Reserved Zone, and soon.

On June 8th, a runoff vote will resolve the results of the April election for president, where neither of the top two candidates got the 50 percent majority required to win. The winner will only have about a month to transition between the old administration and the new one.

Because the presidential outcome has been contested for two months longer than expected — and because the changeover will be so quick — supporters of the Tropical Pacific Seas Reserve cannot predict whether the new government will favor oil or conservation.

“If the Minister of the Environment and the Minister of Energy and Mining come to an agreement, the approval process can happen very quickly,” said Majluf. “But if takes too long, it can be years before the reserved zone is created. Or it might not be created at all.”

Oceana Peru recently joined the fight to protect Peru’s tropical Pacific seas. Learn more about our work in Peru here.