June 22, 2016

Facing a Plague of Invasive Lionfish, Caribbean and Gulf Communities Get Creative

BY: Allison Guy

Humans can’t compete with lionfish for venom, camouflage, or the ability to produce 30,000 young at a time, but there is one arena where we might have lionfish beat: appetite.

This is the second part of a two-part series. Read the first part, The Perfect Invader, here.

If these invaders have an Achilles heel, it’s the fact that they taste great. Firm-fleshed and mild, lionfish have been compared to more familiar species like grouper, snapper or even lobster. And according to Fiona Lewis, owner of the District Fishwife market in Washington, D.C., it once made for one of the best ceviches she’s sampled: “It had a luminous quality. It was just the perfect texture and flavor.”

Most lionfish control efforts focus on getting people to catch and eat as many of these fish as possible. Lionfish derbies, tournaments and festivals have sprung up around the Gulf and Caribbean, with the aim of turning a routine task — invasive species control — into entertainment.

In May, divers at a single tournament in Pensacola, Florida speared over 8,000 fish, a new state record. Attendees were treated to cooking demonstrations, lionfish hors d’ oeuvres and prizes for the biggest and most lionfish caught.

“They are not only getting a delicious meal, but they’re doing something positive for the environment,” said Amanda Nalley, a representative from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. “It’s a feel-good activity.”

To Cook a Predator

Fish suppliers big and small are starting to sell lionfish as the once-niche market for this invader picks up. In May, Whole Foods began selling lionfish in 26 Florida stores — a decision that proved wildly popular with shoppers. “Almost everyone who comes into the seafood department is requesting it, or having conversations about it,” said McKinzey Crossland, a Whole Foods representative.

In Washington, D.C., Lewis started selling lionfish in May after two years trying to track down a non-frozen supply. Her customers rewarded her persistence, praising the fish as “absolutely delicious.”

But there’s a catch to this burgeoning demand. “Even though lionfish is abundant,” Crossland said, “finding a consistent supply is tricky because of how hard they are to catch.”

Lionfish have to be hand-caught by divers with spear guns or small nets. It’s time-consuming work, and because lionfish grow to a maximum of 46 centimeters (18 inches), they rarely offer the cash bonanza of large, lucrative fish like tuna or grouper.

Some hobbyists are happy to hunt regardless of whether or not they turn a profit. But for people who make fishing their livelihood, particularly in poor communities, the hassle of lion-hunting has to be worth the reward.

“Fishers do face a significant opportunity cost when fishing lionfish,” said Jen Chapman, a marine biologist and the country coordinator for Blue Ventures in Belize. “People must be willing to pay more for lionfish than grouper or snapper. This really is the main focus of our campaign at the moment: Increasing demand both in volume and value.”

So far, these efforts seem to be working. In a 2015 survey conducted by Blue Ventures, lionfish numbers in the majority of 50 sites along Belize’s barrier reef were below the threshold level considered harmful to native fish.

Cautioning that more data analysis is needed, Chapman was still optimistic. “It looks like lionfish are larger and more abundant within no-take zones than in areas accessible to fishers,” she said. “This suggests that the fishery approach is working.”

Pulling the Weeds

Lionfishes’ most potent defense against humans is not venom, but depth. Non-technical divers can safely descend no deeper than 40 meters (130 feet), leaving lionfish a 260 meter (850 foot) band where they can live and reproduce unmolested.

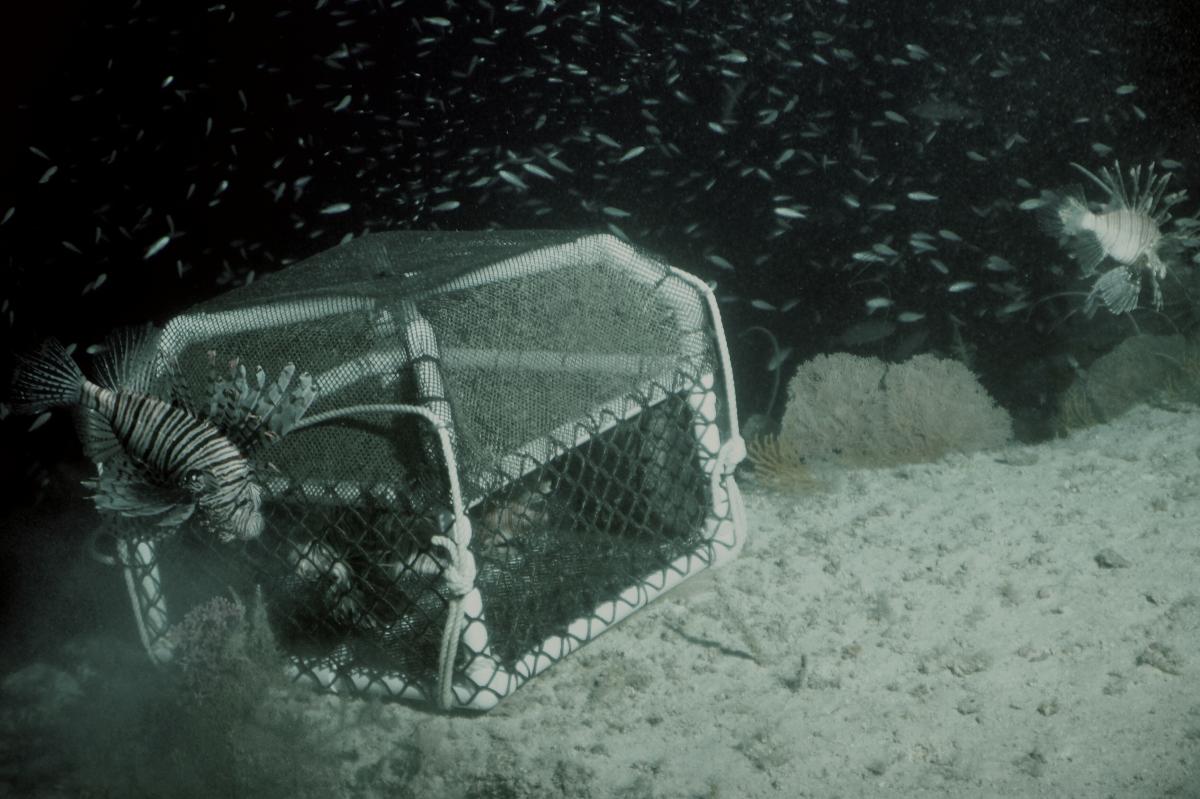

Several groups are experimenting with traps to target the fish that so far have remained out of reach.

One such trap is under development by Bob Hickerson and Maria Andreau, a husband-and-wife team that runs lionfish derbies and creates lion-specific spearfishing gear. The trap, equipped with a digital sensor, opens only when it identifies a lionfish’s signature stripes — eliminating the accidental capture of native species.

In late May, Hickerson and Andreau deployed two prototype “lionfish aggregators” off Curacao. One month later, footage from a remotely operated vehicle showed several lionfish clustered around one aggregator device at 95 meters (312 feet).

Apart from depth, another big roadblock for lionfish control has been how little we know about them on their home turf. Something must control their numbers in the Indo-Pacific, Green explained, but it’s a still a mystery whether it’s parasites, predators, competition between the 12 species of lionfish, or something else.

Despite the promise of new technologies and research, experts are skeptical that eradication will ever be possible — or even desirable. Compared to initiatives that aim for total eradication, partial removal of lionfish is far more cost-effective and just as beneficial to native species. Below a certain density, lionfish don’t have much of an impact on other fish.

The trick, Green said, is in knowing where that threshold lies, and keeping fishers motived to stick to it. “This is essentially a ‘pulling the weeds from your garden’ strategy,” she said. “It’s ongoing, it takes effort, and you have to keep revisiting it in order to keep the problem in check.”

Nalley agreed. “’Eradicate’ is not really a word we use when it comes to lionfish,” she said. “I don’t have a crystal ball. But what I do see is an increasing number of people harvesting them commercially. I see them more on people’s plates. And I think more people will eventually build better and bigger ways to catch them.”

Oceana Belize works with fishers, chefs, suppliers and conservation groups on the “Fish Right, Eat Right” campaign, which promotes the use of sustainable seafood, including lionfish.