June 7, 2016

Like Father, Not Like Spawn: The Beautiful and Bizarre “Disguises” of Baby Fish

BY: Allison Guy

The old saw “like father, like son” doesn’t hold water when it comes to fish. During their earliest stages of life, many baby fish eat different foods from their parents, live in different habitats, and contend with a slew of predators that see small fry as a perfect snack.

Because of this, fish larvae can look so unlike adults that even scientists can be stumped when trying to identify their species. Below, learn about four of the most extreme transformations from baby to adult fish — and find out why these youngsters need such puzzling “disguises” to survive.

Slimy Secrets

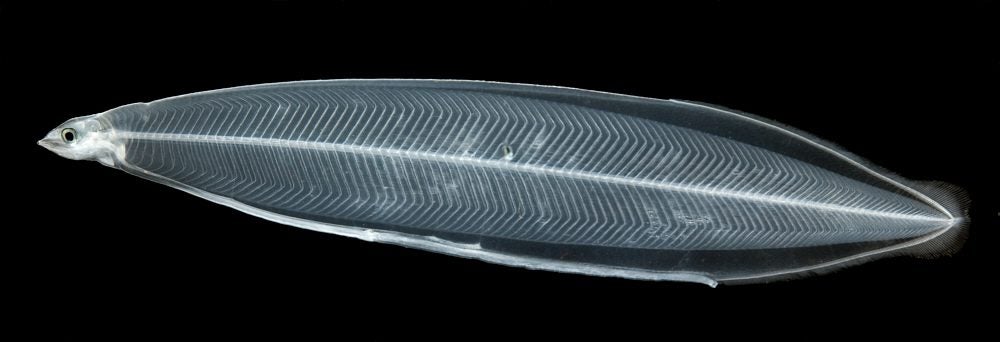

For almost a century, this transparent, leaf-shaped creature and other animals like it had a bad case of mistaken identity. At first, scientists put these fish into their own genus, Leptocephalus — literally “slime head” — and assumed each type represented its own distinct species. Only in 1817 did biologists realize that these see-through animals were actually the larval stage of eels like conger, garden, or moray eels.

Baby eels have several traits that make them a headache to study.

First, they’re only a few tissue layers thick and filled with a transparent jelly, making it hard for predators and scientists to spot them. And second, they can also grow unusually big for larvae — up to 1 meter (3 feet) long. One Danish research vessel reportedly captured a 1.8 meter (6 foot) specimen in 1930. Because they are well-developed, strong swimmers, they’re better able to avoid researchers’ nets compared to the millimeters-long larvae of other types of fish.![An adult American eel looks almost nothing like its larval form [above]. <i> Credit: Clinton & Charles Robertson / Creative Commons </i>](https://oceana.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/4015394951_cd57d75295_o.jpg)

But the main mystery around eel larvae is their odd anatomy. The only physical trait that marine eels keep constant throughout their transformation from babies to adults are blocks of muscle that match the number of vertebrae they’ll have when fully grown.

If that makes it sound like it’s next to impossible to know the species of a “slime head” just by looking at it — it is. Scientists once had to capture a leptocephalus and raise it to adulthood to figure out its species. Now, genetic identification can do the trick.

Flat Freaks

Baby flatfish such as flounder or halibut have elaborate fins and filaments that disappear as they mature. But the oddest thing about flatfish larvae is how they’re strange for being “normal.” Right after it hatches, a flatfish looks like a standard, symmetrical fish, with one eye and either side of its head.

But at about a month of age, the larva’s skull starts to transform. Bones twist and soften, connective tissue thickens, and one eye migrates over the top of the head and joins its partner on the other side.

With both eyes jammed together on one side of its body, the fish settles on the seafloor to live out its adult life as an ambush predator. This extreme metamorphosis makes flatfish the most asymmetrical group of vertebrates around.

Baffling Basslets

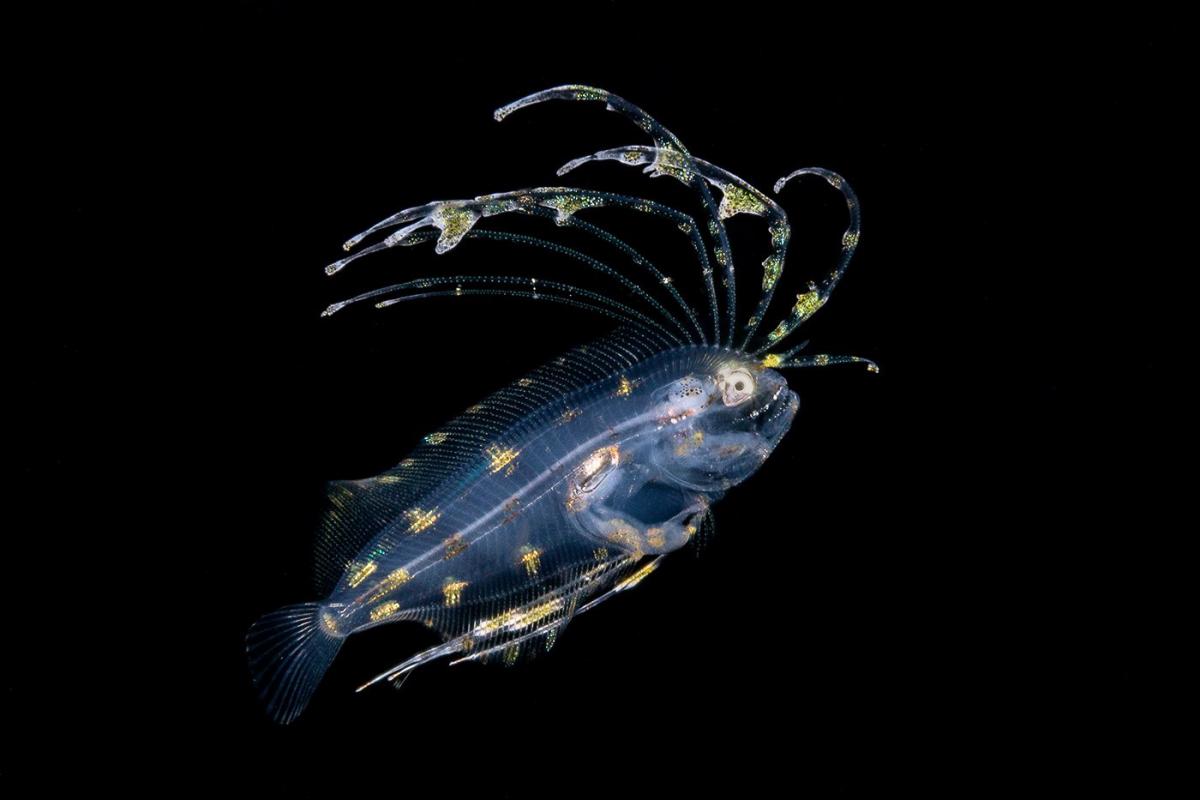

Basslets in the Liopropoma genus are small, colorful members of the grouper family. As adults, they sport vivid stripes and spots, and settle into secretive lives in the crevasses of coral reefs. But when they’re larvae, they drift in the open ocean as part of the huge number of tiny species that make up the plankton community.

Basslets in the Liopropoma genus are small, colorful members of the grouper family. As adults, they sport vivid stripes and spots, and settle into secretive lives in the crevasses of coral reefs. But when they’re larvae, they drift in the open ocean as part of the huge number of tiny species that make up the plankton community.

Unlike the streamlined adults, baby basslets boast flamboyant spines and banner-like filaments. The purpose of these ornaments is unknown, but they likely help the larva look bigger than it really is. Or, they may trick predators into attacking the filaments instead of the basslet.

As with eels, it can be impossible to tell from appearance alone which larvae will grow up to be what kind of adult. Researchers instead rely on DNA sequencing to figure out if they’ve found a candy basslet (Liopropoma carmabi), a peppermint basslet (Liopropoma rubre), or something else entirely.

“Something else entirely” ended up being the answer for one unusual baby basslet decked out with seven spines along its back. After analyzing its DNA, scientists discovered that the orange-and-white larva belonged to a brand new species, the yellow-spotted golden bass (Liopropoma olneyi). When they hit adulthood, juvenile golden bass lose their spines and gain a splash of bright yellow along their backs.

“Something else entirely” ended up being the answer for one unusual baby basslet decked out with seven spines along its back. After analyzing its DNA, scientists discovered that the orange-and-white larva belonged to a brand new species, the yellow-spotted golden bass (Liopropoma olneyi). When they hit adulthood, juvenile golden bass lose their spines and gain a splash of bright yellow along their backs.

Baby Behemoths

This 10 millimeter (0.5 inches) long prickly ball will eventually grow up to be one of the biggest — and weirdest — fish in the sea. An adult sharptail mola (Masturus lanceolatus) can get as long as 3.4 meters (11 feet) and can weigh up to 2,000 kilograms (4,400 pounds).

But size isn’t the strangest thing about these fish. They have no tail or ribs, and their spines are fused into an inflexible mass. Adults sprout a secondary “tail” that gives them their common name, although sharptail mola don’t actually use this triangular lobe for swimming. Instead, they get around by rowing the oar-like fins on their backs and bellies.

The sharptail mola’s close relative, the ocean mola (Mola mola), produces more eggs than any other vertebrate on earth — up to 300 million at a time. When these eggs hatch, the larvae weigh just one gram. In the years that follow, they can grow up to 60 million times bigger if they reach their maximum size.

Around the world, Oceana campaigns to protect fish big and small from the threats of overfishing, irresponsible fishing gear, and habitat destruction. Donate today to help support our work.