February 1, 2016

Fishing Forever: The Lobstermen Behind Chile’s Certified-Sustainable Fishery

BY: Allison Guy

For many of the 900 people who call Chile’s Juan Fernández archipelago home, lobster is life. The Juan Fernández rock lobster (Jasus frontalis) supports 70 percent of the economy on these remote, rocky islands. Long before “sustainability” became a global catchphrase, the area’s lobstermen have followed practical rules to protect their lobsters and livelihoods for over a century.

How to fish forever

In 2015, the Juan Fernández lobster fishery achieved a coveted Marine Stewardship Council certification. But while this recognition is recent, the sustainability of the lobster fishery is not.

Three islands — Robison Crusoe, Santa Clara and Alexander Selkirk — and a chain of underwater seamounts collectively form the Juan Fernández archipelago, located 400 miles (644 kilometers) west of Chile’s coastline. This archipelago, and the Desventuradas Islands 517 miles (832 kilometers) to the north, form the fishing grounds for the islands’ artisanal lobster industry.

For hundreds of years, the sheer remoteness of these islands curbed fishing pressure on the lobster. Unlike fur pelts and rendered oil, the demand for which nearly exterminated the Juan Fernández fur seal, lobster could not be shipped far before spoiling in the days before airplanes and refrigeration.

By the 1940s, however, it had become clear to the people of Juan Fernández that the lobster fishery needed formal protection. The community agreed on a 4-month seasonal closure each year, prohibited the sale of any lobster under 11 inches (28 centimeters) long, and mandated that all females with eggs, regardless of size, be released back to the sea.

Perhaps most importantly, fishing rights cannot be bought and sold. Instead, they are passed down from parent to child. And each of the 150 or so fishing families has its own marca, a designated fishing ground that is kept secret from outsiders.

While the rest of the world has expanded its fishing fleet and poured technology into tracking down dwindling fish stocks, the number of boats and the types of gear in use on Juan Fernández has remained essentially unchanged in the last 50 years.

These measures, while simple, were pioneering for the time and they’ve proven their worth. “After small catch declines in the 1980s, there are now more lobsters than ever,” explains Alex Muñoz, vice president of Oceana Chile. “Juan Fernández is proof that with proper management of resources, it’s possible to ‘fish forever’.”

A lobster like no other

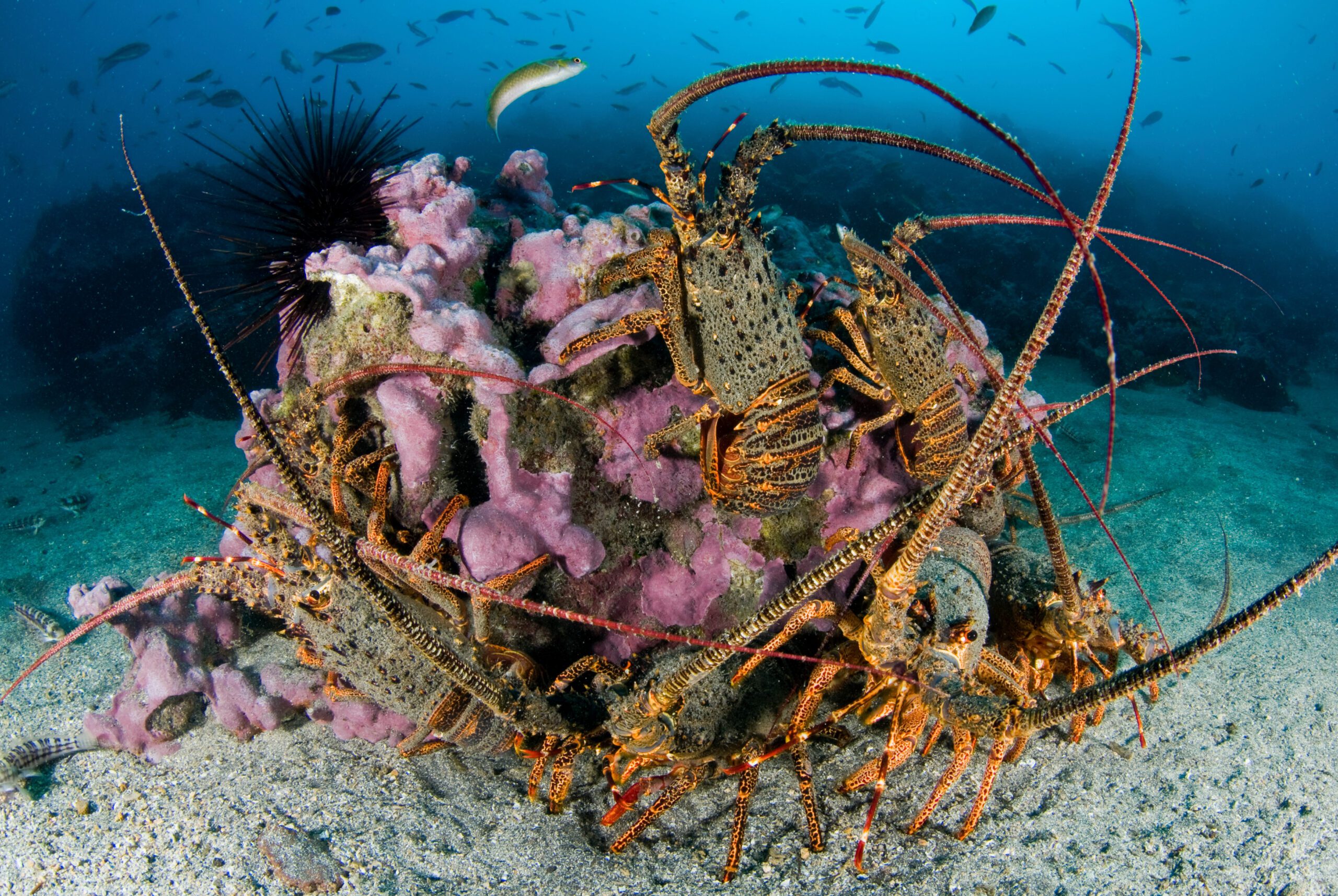

The target of all this attention can be found crawling amongst the candy pink anemones and kelp groves that dot the archipelago’s underwater slopes. The Juan Fernández rock lobster is found only around the archipelago and the Desventuradas Islands.

These prized crustaceans range in color from gray-green to a vivid orange, and grow as big as 15 pounds (6.8 kilograms). As with other members of the spiny lobster family, they lack the giant claws of the more familiar American lobster (Homarus americanus). Unlike their northern cousins, it’s the tails on the Juan Fernández lobster that receive top billing. For the last five years, the islands have produced approximately 110 tons (100 metric tons) of lobster tail each year, destined to be sold for about 20 dollars apiece in China and France.

Despite the challenges of catching and shipping their valuable product — while trying to also protect the lobsters’ population — the islands’ fishery has remained strong.

There are likely many reasons why the lobstermen have endured, but Muñoz suspects they boil down to the psychology of isolation. “For most of their history, the people of Juan Fernández were very aware that they were alone. They knew that if they lost their resources, they would lose everything,” he says. “This is a lesson that the rest of the world needs to learn.”

Oceana works in Chile and around the world to promote sustainable fishing practices and protect marine wildlife. Donate now to help Oceana save the oceans and feed the world.