April 20, 2017

Forget Giraffes: 5 Reasons Why Sharks Have the Coolest Pregnancies

BY: Allison Guy

Last weekend, what seemed half the globe watched with bated breath as April the giraffe’s baby took a 6-foot tumble from the womb into the world. As epic as giraffe birth is — That terrific fall! Those wobbly legs! — shark mothers have April beat fins-down in the pregnancy department, and here are five reasons why.

5. Marathon gestation

By the time that a human mother is ready to give birth, her nine-month pregnancy can feel like an eternity. But human gestation is a speedy affair compared to the spiny dogfish shark, which has one of longest confirmed pregnancies of any vertebrate —up to 2 years.

Other shark species may have even dogfish beat. Some scientists have estimated that basking sharks may have pregnancies that last for anywhere from 2.6 to 3.5 years, although other researchers have disputed this. Frilled sharks may also be champion incubators, holding on to their babies for up to 3.5 years.

All of these sharks live in cold waters, which may explain why they’re remarkable slowpokes when it comes to giving birth — chilly temperatures tend to slow down your metabolism if you’re a cold-blooded creature.

4. Conveyer belt babies

Adding to the discomfort of a 2-year gestation, some deep sea sharks are also able to get pregnant as soon they give birth. They accomplish this by cycling through a conveyer belt of babies, with fully formed pups at the bottom of the uterus and large eggs waiting to be fertilized at the top. There is even evidence that certain sharks can store sperm, so they can fertilize those big, well-developed eggs as soon as their siblings vacate the womb. Adding to the burden of perpetual pregnancy is the fact that sharks have two uteruses — so they’re not only always pregnant, but doubly so.

3. Uterus milk and tasty eggs

Some shark species are viviparious, meaning they give birth to live young. In the early stages of their development, shark fetuses live off the nutrients in the egg yolk attached to their bellies. But the fetuses of many species exhaust their egg yolks long before they’re ready to be born. How to feed a ravenous baby once the larder’s been emptied?

In some species, the yolk sack bonds with the mother’s uterus so the baby shark can absorb nutrients directly from her bloodstream. In other species, like hammerheads, the mother’s uterus secretes a milk-like substance to nourish the baby. And sharks including threshers, makos and great whites have an even odder solution: They feed their fetuses an endless stream of unfertilized eggs.

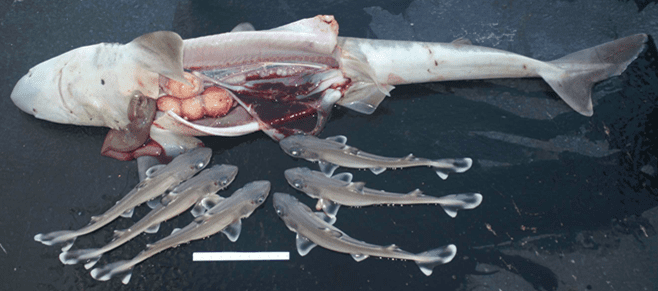

2. Sibling cannibalism

Sand tiger sharks have the most ghoulish fix for hungry babies: The fetuses devour each other in-utero until there’s just one pup remaining in each of their twin wombs. This uterine bloodbath is thought to have developed because a litter of sand tiger pups usually has multiple fathers — and each dad is engaged in a proxy war for his genes to take the upper hand. The “winning” fetus gets all the nutrients from its siblings and a roomy womb to develop into an unusually big baby, over 1 meter (3 feet) long at birth. Being born large and well-developed helps these newborn predators survive in a hostile ocean.

1. Virgin birth

There’s one final shark trick that April the giraffe could only pull off with divine intervention: Virgin birth. Female sharks of several species are able to reproduce without any help from a male, a phenomenon known as parthenogenesis.

Leonie, a captive zebra shark in Australia’s Reef HQ Aquarium, laid 41 eggs in April 2016, three of which hatched into healthy pups. Though female sharks can store sperm for years on end, DNA testing confirmed that Leonie’s offspring were genetic clones of their mother. Other aquarium sharks, perhaps frustrated by their lack of accessible mates, have taken matters into their own fins. Tidbit, a blacktip shark at the Virginia Aquarium, reproduced asexually in 2007, as did a bonnethead at the Omaha Zoo in 2001.

The frequency of this phenomenon in aquariums suggests that it likely occurs in free-swimming sharks as well. So far parthenogenesis in sharks hasn’t been observed the wild, though it has been seen in endangered sawfish, which are close relatives of sharks.

From clones to cannibalism, sharks mamas boast some of the most dramatic pregnancies around. Just remember that when a dogfish shark invites you to her first baby shower, save your money: She’s going to be popping out pups for a long time.