April 2, 2020

How a strategic fishery closure helped save Spain’s beloved anchovy

The 2005 European anchovy season in Spain began like any other. On a chilly evening in early March, small fishing fleets motored into the Cantabrian Sea – the inshore regions of the Bay of Biscay – on the hunt for schools of the small blue and silver fish.

Among the 200-odd boats was the 100-foot Itsas Eder, Basque for “beautiful sea.” It departed from the sleepy town of Hondarribia, nestled against the French border in the heart of Basque country. The boat’s captain was 44-year-old Eugenio Elduayen, a handsome, burly man whose family had been fishing for at least four generations. Elduayen had witnessed many changes since he first started working with his grandfather in the 1970s: the introduction of fishing licenses, the arrival of a rival French fleet, more comfortable boats, better nets, boom years when their boats overflowed with fish, and storms that lashed the sea and kept them land-bound. One thing remained constant, however: the schools of anchovy that gathered at the surface of the sea at night, which Elduayen’s crew would encircle and scoop up with nets.

In March of 2005, however, Elduayen saw something different. He and two-dozen other captains from Hondarribia crisscrossed the bay’s inshore waters, checking their sonar screens for signs of anchovy. After a few nights, however, they were forced to give up and return to shore. The anchovy had simply disappeared. “We had always seen the anchovy,” Elduayen said. “We never thought it would end.”

These weren’t just unlucky fishing trips; they were the telltale signs of a fishery collapse. The story could have ended there, with the demise of the local anchovy population, but a strategic fishery closure helped revive this important species. According to a study published in December 2019, a closure like the one that was ultimately implemented – after campaigning by Oceana – could have prevented the anchovy collapse in the first place.

It wasn’t easy, but science-based fisheries management saved Spain’s anchovy, and in doing so, it put fishers back to work and preserved an important part of Basque culture and cuisine.

The queen of the sea

The anchovies from Spain’s Atlantic coast are considered one of the world’s great delicacies. Chefs say the Bay of Biscay’s cool waters give these succulent, complex fish an added layer of fat that makes them tender. The secret to their greatness isn’t just the anchovies themselves, but also the way the locals cure and prepare them. The resulting fillets, encased in olive oil and packaged in colorful tins, can run $3 a fish. These anchovies make their way around the world, ending up in meat dishes, pasta sauces and, of course, salad niçoise.

The European anchovy, one of six commercial species of anchovy, is not just a vital part of Basque cuisine. This diminutive creature, between five and six inches long when caught, also feeds the marine ecosystem in the Bay of Biscay, an 86,000-square-mile body of water almost half the size of Spain itself. Swimming in schools with its mouth agape, the anchovy filters plankton and fish eggs from the water. The anchovy in turn are feasted on by many species, from hake to dolphins to seabirds. “It gives life to Cantabria,” Elduayen said. “The anchovy is the queen of the sea.”

In March 2005, things were meant to unfold much as they had for the last 100 years. After fishing at night and through the early hours, the fishermen would have been met at the town docks at 7 a.m. by local buyers who would inspect the crates of anchovies and bid on the catches. The fish would then be whisked to a factory to be cleaned and packed into barrels with salt for nine months of curing. But that year, things were different.

Empty nets

By early May, fishermen in the Bay of Biscay had managed to catch just 1% of their normal haul. The European Union called it “a complete crash of the commercial fishery.”

Oceana had also been fearing trouble for some time. The Agriculture and Fisheries Council, made up of ministers from the 28 European Union member states, repeatedly voted to set yearly catch quotas far above the limits recommended by scientists, despite intensive lobbying from Oceana. “If you disregard the scientific advice for too many years, you have a huge problem,” said Javier López, Fisheries Campaign Manager for Oceana in Europe.

When the Bay of Biscay anchovy started to falter, the independent scientific body advising the EU recommended a total allowable catch (TAC) of 11,000 metric tons for 2003. The Council voted to set it at the same amount they had since 1995: 33,000 metric tons. Fishermen landed just 10,600 metric tons. Similar scenarios played out in 2004 and 2005, with the TAC double or triple the scientific advice and the actual catch. By 2005, it was too late. The fishermen couldn’t have hauled in their TAC of 30,000 metric tons if they had wanted to. They could hardly find a single anchovy in the sea.

Collapse and catastrophe

What caused the collapse of the stock? The obvious answer would be overfishing, but there were also environmental stressors, according to Andrés Uriarte, a renowned Spanish fisheries expert who has monitored fish in the Bay of Biscay since the late 1980s. The direction of the winds, salinity, currents, and water temperatures all play a role in how many larvae and juveniles survive to become adult anchovies.

However, fishing still played a significant part, Uriarte explained, by removing adults that otherwise would have spawned. When one year’s larvae fail to grow into adults, and this happens year after year, the total number of anchovy can sink to dangerously low levels. By 2005, the adult stock had declined to the point that the catch set for that year – 30,000 metric tons – was two to three times the amount of all the remaining adult anchovy in the bay.

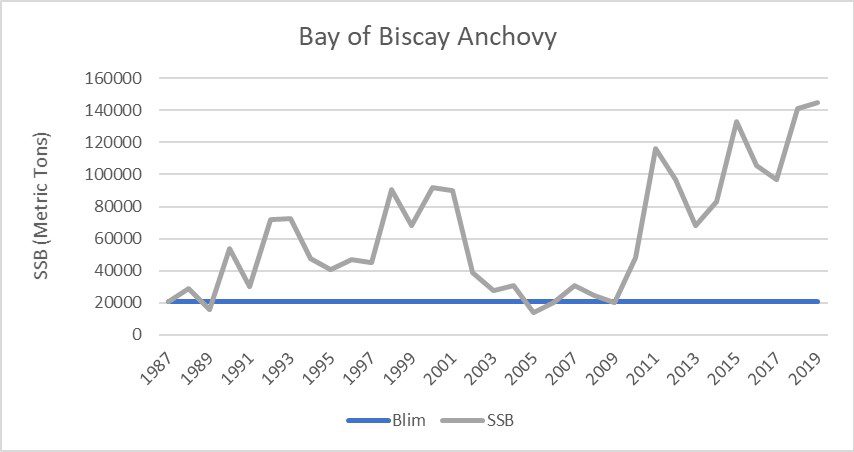

Urged on by Oceana and its allies, the European Union decided to shut the fishery on July 1, 2005, and later extended the ban through the winter. When national ministers gathered in Brussels that December to discuss the coming March harvest, however, they were as optimistic as ever, setting the TAC at 5,000 metric tons, despite scientific advice to keep the fishery closed. Scientists drew the line for a moratorium at a population level of 28,000 metric tons or less. In the spring, scientists found the stock had crossed that line and then some: It was at just 18,640 metric tons. The fishery shut again in July 2006.

The closure was not easy for fishermen. In losing the anchovy, Elduayen and his Basque compatriots, who bring home 85% of all Spanish anchovy landings from the bay, lost almost 30% of their yearly revenue. The closure forced some out of the trade, particularly smaller operators that were more dependent on anchovy. From 2005 to 2009, the Basque fleet shrunk by 5% every year, and local canneries had replaced Biscay anchovy with imports from abroad. Still, the fishermen of Hondarribia supported this closure. “We realized we were facing a catastrophe,” Elduayen said.

Many involved thought the closure would only last for a year, but it dragged on as the anchovies struggled to recover.

Devising a plan

There was bickering and discord as the region tried to deal with the crisis. But there were also positive signs. “We would go out to fish albacore and, little by little, we would see anchovy and say, ‘You know, this is getting better; it’s recuperating,’” Elduayen said. “We held on and were patient.”

In the meantime, the Basque fishermen took action. Up to that point, “the quota had always been just something written on a piece of paper,” Elduayen said. “Even if there were no anchovies in the sea, the politicians would write 33,000 metric tons, and that was it.” After the collapse, the Basque fishermen’s attitude to this “changed radically,” Elduayen recalled. “We made the decision that we must always go with biological facts.” They started by reaching out to Uriarte and his team from AZTI, who agreed to work with them.

Together, Uriarte and the fishermen decided to set up a plan. It would have one hard-and-fast rule: That catch limits be set according to the number of anchovy in the sea. If the stock fell below a certain limit, the fishery would close. If the population grew, fishermen would be allowed to net more. But they could never take more than 33,000 metric tons. In response to this proposal, the European Commission swung into action, bringing on board scientists and fishermen from Spain and France, as well as others involved in the fishery, to begin formalizing the new management plan. By 2008, the plan was ready. But were the anchovies?

The queen returns

Less than two years later, in late 2009, the fish began to show signs of a real comeback, and by spring 2010 the fishery had reopened with a TAC of 7,000 metric tons. On March 1, the Basque fishermen headed out into the bay for the first time in four years, once again hauling up nets full of wriggling, silver fish. By June 10, Elduayen and his compatriots had brought home their 5,400 metric tons. The French then dove in, scooping up their quota of 1,600 metric tons.

The plan devised by Uriarte and the fishermen has worked well. “We go hand in hand with the biologists,” Elduayen said. “They recommend and they let us recommend. Now we set the quotas instead of having the paper quotas telling us [what to do].”

The annual catch has climbed in step with rebounding anchovy populations. In 2016, the catch jumped to a little over 18,000 metric tons, and in 2019, it swelled again to roughly 26,600 metric tons. The biomass of all spawning-age anchovies last year was the highest it has ever been since the Biscay anchovy surveys began in 1987.

A 2019 study also confirmed the benefit of giving fish the chance to recuperate. The researchers, including lead author Juan Bueno-Pardo, wrote that the recovery of the anchovy population “was mainly triggered by the closure of the fishery for five years,” coupled with favorable seasonal conditions.

Oceana’s López said that despite a “history of mismanagement,” the fact that the anchovy were given time to recover is a great achievement. “It is not very common that you are able to convince the EU to close a fishery,” he said.

For his part, Elduayen and his community are “rejoicing” now that the anchovy are back. “It’s a beautiful sight to see the Cantabria so healthy,” he said. But his community’s years without the fish helped them grow in unexpected ways. “What I want to carry with me to the next generation, because I have a few years left, is this: The sea isn’t without end. We have to encourage it, and if we take care of it, it gives.”

A version of this story was originally published in November 2017. It was updated in April 2020 to reflect new data.