February 26, 2020

Humans hunted North Atlantic right whales to near-extinction. Now we must save them.

BY: Emily Nuñez

What adjectives come to mind when you think of whales? Intelligent? Beautiful? Maybe majestic?

These would all be reasonable answers by today’s standards, but past generations may have described them differently. For centuries, whales were regarded as vicious beasts or dispensable commodities, and not much in between.

As marine biologist Dr. Chris Lowe explained on an episode of the Ologies podcast, “150 years ago if we walked down San Pedro, or we walked down New Bedford, and you ask people what kind of animal they thought a whale was, they would say horrible things. Whales were … they were demons!”

Take for instance the 1839 magazine article that reportedly inspired Herman Melville’s world-famous novel, Moby-Dick. In the article, the author characterizes an albino whale named Mocha Dick as a “renowned monster, who had come off victorious in a hundred fights with his pursuers.”

Revenge was a powerful motivator for the fictional Captain Ahab, but the justification for most whaling in the West was the value of whale byproducts like oil and baleen – the bristles inside a whale’s mouth that help them filter food. In colonial America, whaling was regarded as a dangerous but respectable profession, and there was no shortage of men willing to do the job.

While several types of whale have been hunted by humans, one of the species that never fully recovered is the Eubalaena glacialis, an endangered black whale that’s known today as the North Atlantic right whale.

The whale with many names

Historically, the marine mammal now called the North Atlantic right whale was known as the black whale, nordcaper, sletback, and seven-foot bone whale – a reference to the average length of their baleen plates – by different people at different points in time.

But for hundreds of years, no one really knew what kind of whale it was, according to Michael Dyer, a curator of maritime history at the New Bedford Whaling Museum in Massachusetts.

“It was not identified as a distinct species until 1860, and over time its name became confused with that of the bowhead whale, which was also hunted for its long slabs of marketable baleen,” Dyer tells Oceana. “The whales that were hunted in places such as the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Davis Strait were most likely a mix of black whales and bowhead whales.”

Today, North Atlantic right whales are one of the world’s most endangered whales. To understand how this leviathan creature was driven to the brink of extinction, we need to look back to the challenges put forth by both nature and man.

A series of setbacks

DNA evidence shows that North Atlantic right whales were already low in genetic variability by the time commercial whaling got its start. Some researchers have suggested that the whales’ genetic pool may have thinned out during the last Ice Age, roughly 18,000 years ago, at a time when coastal habitat losses were severe.

Whatever the explanation may be, humans certainly made matters worse. The Basques, a population of savvy seafarers, were among the first known commercial whalers. As early as the year 1000, they were regularly hunting North Atlantic right whales off their home shores in present-day Spain and France, in the Bay of Biscay. At the time, whale meat was in high demand because the Catholic church declared that warm, “red-blooded” meat should not be eaten on holy days, of which there were 166 per year. (Whales were regarded – wrongly – as cold-blooded creatures because they lived underwater.)

Beginning in the mid-16th century, the Basques, followed by the Dutch and English, turned their attention to North America and began hunting bowhead whales in what are now Canadian waters. But it wasn’t until the mid-17th century that American colonists started hunting migrating right whales from lookout points on Cape Cod and Long Island.

According to Dyer, commercial whaling in North America began when colonists started finding “drift whales,” or cetaceans that had been beached or washed ashore dead.

“It quickly escalated into a shore-based commercial hunt,” Dyer says. “Both Cape Cod and Long Island have high dunes with superb views across the water, and as the right whales – and other species, including humpbacks – arrived predictably, they were easily spotted.”

This was the beginning of what would end up being a relatively short-lived hunt for right whales in North America. The consequences, however, are still being felt today.

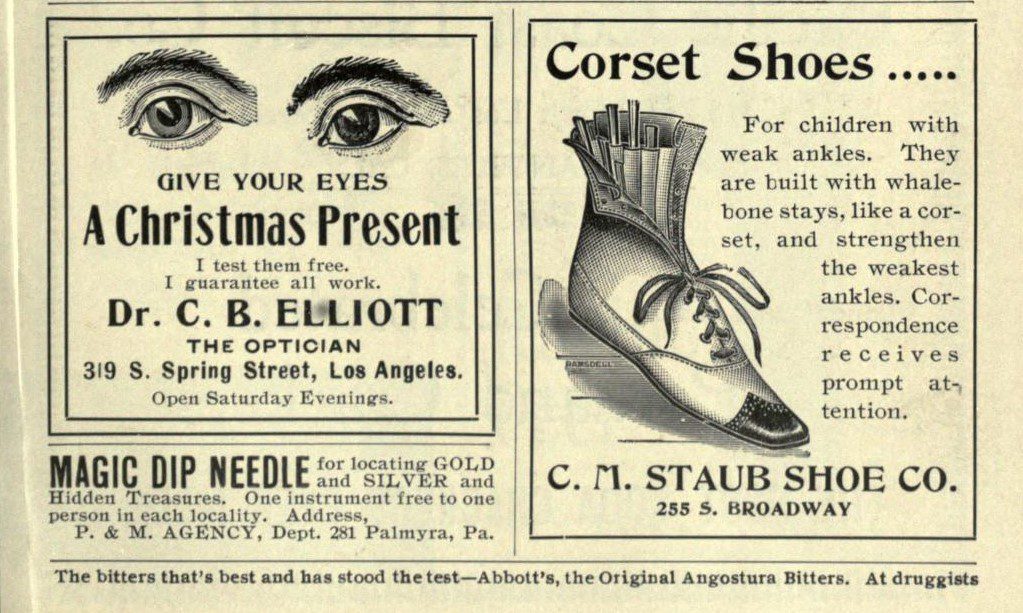

Crossbows and corsets

“Yankee whalers,” as the American hunters came to be known, found a lucrative market for the baleen that hangs from the roofs of right whale mouths. This keratin-rich substance (sometimes confusingly called “whalebone,” despite not being bone) was fashioned into a variety of 19th-century products, from crossbows to harpsichord parts to the frames that gave umbrellas and corsets their shape.

One of the better-known whale products, of course, was oil. It was extracted from the blubber of several different species of whale, then used for illumination or manufacturing purposes.

As Richard Ellis writes in Men and Whales, “That whales had to die to provide these things is a fact of seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century life.”

The predictable migratory routes of North Atlantic right whales made them a dependable resource – until right around the time of the American Revolution, when they became scarcer in the North Atlantic. Pre-whaling estimates of North Atlantic right whales vary greatly, but experts put it somewhere between 9,000 and 21,000 individuals.

Today, the species has just around 400 members and is veering dangerously close to the edge of extinction.

The right thing to do

Fast forward to 2020, and it’s clear that North Atlantic right whales are still suffering at the hands of humans, despite no longer being hunted by commercial whalers. The two biggest dangers they face are ships and fishing gear, which can cause collisions and severe entanglement-related injuries.

Too often, these run-ins turn fatal. At least 30 right whales died between 2017 and 2020, dealing a devastating blow to a species that can’t afford to lose any members. More bad news arrived in December 2019 and January 2020, when an entangled right whale, with yellow rope trailing from its mouth, was spotted three times off the coast of Massachusetts. Around the same time, a newborn right whale calf was spotted off of Georgia’s coast with life-threatening injuries to its head – a casualty likely caused by a boat’s propeller.

If we want to save this species, there’s no time to lose.

“If we don’t act fast, we could see a large whale species go extinct in the Atlantic Ocean for the first time in centuries,” said Jacqueline Savitz, chief policy officer at Oceana. “Even a single death by ship strike or entanglement in a given year is too much. Speed and convenience cannot be prioritized over the survival of this iconic species.”

Last fall, Oceana launched a binational campaign in Canada and the U.S. to save North Atlantic right whales. For it to be successful, both governments must take action to reduce the amount of vertical fishing lines in their waters, as well as other types of gear that are capable of severely injuring right whales. Strategic fishery closures in areas where whales are present can also help shield the animals from harm.

To reduce ship strikes, it’s imperative that seasonal speed restrictions be enacted in areas where right whales are known to frequent. Enhanced efforts in the areas of research, fisheries monitoring, and vessel tracking will also go a long way towards helping this species recover.

Oceana is working to make these changes happen. With the right protections in place, it’s still possible to save this majestic species. We don’t have to make the same mistakes as the Yankee hunters who viewed right whales as little more than commodities. Now is our chance to finally take a stand and do right by right whales.

To learn more about how you can help save North Atlantic right whales, visit Oceana’s campaign page or sign your name here to tell the U.S. and Canadian governments to take action.