June 29, 2016

Maligned as Lazy and Toxic, Greenland Sharks Are Smarter than You Think

BY: Allison Guy

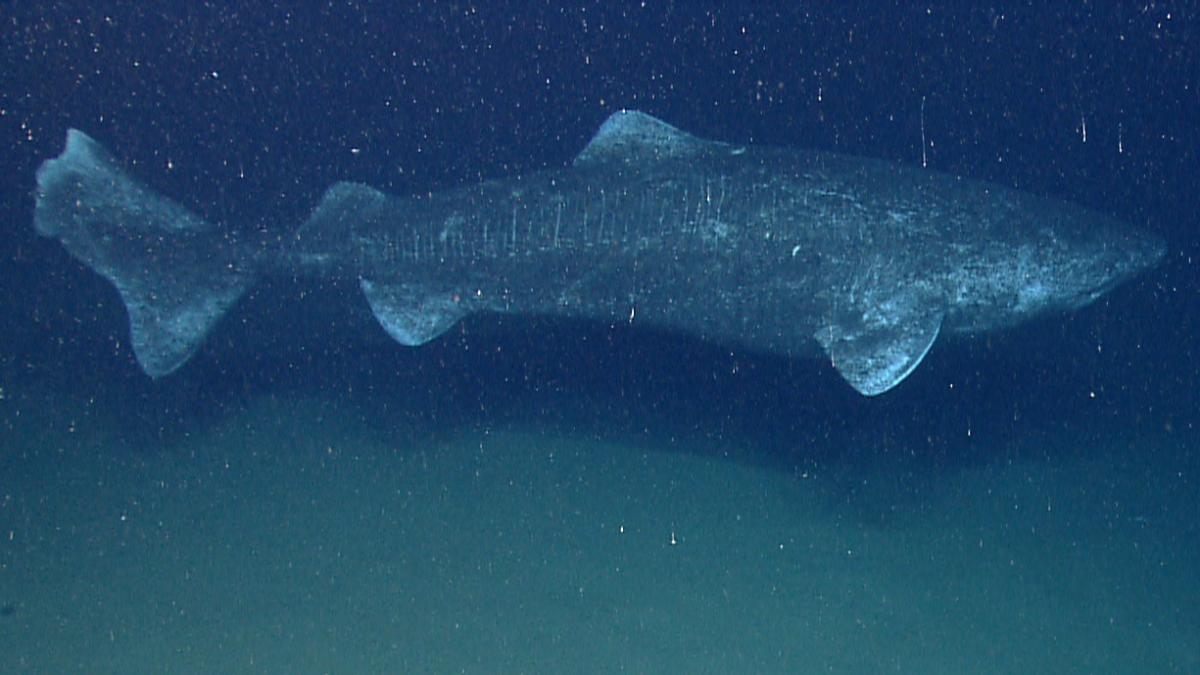

Compared to its sporty relatives, the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) is a real clunker: Blind, plodding and unlucky in the looks department. But like the proverbial tortoise racing the hare, this cold-loving species proves that sloth can be a recipe for success.

Big and bad

Greenland sharks suffer from a toxic reputation — literally. Like many other polar fish, their flesh contains high concentrations of natural antifreeze. According to a handful of reports, Greenland shark meat is so toxic it can make sled dogs vomit and ravens act drunk. But this is likely a case of false advertising. The antifreeze compound in their tissue is toxic, but only mildly — an adult would have to eat around 20 kilograms (44 pounds) of shark at one sitting just to feel woozy

Along with ‘most toxic,’ Greenlands have been saddled with another unearned title: ‘laziest.’ Even their Latin name, Somniosus microcephalus, leaves something to be desired: “the sleepy small-head.”

While it’s true that they mosey along at only about 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) an hour, that’s actually not far off the average shark cruising rate of about 2.4 kilometers (1.5 miles) per hour for a large shark. And at up to 7.3 meters (24 feet) long, Greenland sharks are among the world’s biggest.

These sharks could be forgiven for their glacial pace. Along with their close relative, the Pacific sleeper shark (Somniosus pacificus), they’re the only shark on earth that can handle year-round icy conditions. While the porbeagle shark can tolerate temperatures as cold as 2 degrees C (36 degrees F), Greenland sharks happily bask in water at -1.8 degrees C (29 degrees F).

Permanent blinders

The Greenland’s bumbling reputation is compounded by the fact that almost all of them are blind, or close to it. Though they’re born with small but functional eyes, up to 100 percent of the adults in a local population will have small, parasitic crustaceans (Ommatokoita elongata) hitching a ride on the sharks’ corneas.

Each eye usually hosts one adult female along with several larvae. They nibble away at the shark’s cornea tissue, destroying its vision in the process. Think of it as the world’s most gruesome family picnic.

Infested Greenland sharks can likely see hazy patterns of dark and light, but not much else. This ophthalmological nightmare is offset by their exquisite sense of smell — a blessing for a scavenger that needs to sniff out the bouquet of rotting meat.

Anything that winds up dead in the sea is fair game for these sleepers: fish, seals, whales, dogs, horses, reindeer, moose and bears.

There’s a vivid — and entirely unsubstantiated — tale that Greenland sharks ambush reindeer that come to the mouths of rivers to drink. The more likely explanation is that the deer remains came from a beast that died upstream and was washed out to sea, or that drowned while out for a swim.

The air up there

These slow-motion scavengers might have a more active side. The big proportion of seals found in dissected Greenland shark guts suggests that they’re not randomly chowing down on whatever carcasses come their way. These sharks may have learned to rely on other, swifter killers: Polar bears and asphyxiation.

Seals often take to sleeping in the water when polar bears are around. According to one theory, this makes them easy pickings for a stealthy shark. Another line of reasoning goes that Greenland sharks camp out near the breathing holes that seals carve in sea ice, confident that sooner or later dinner will come along.

Researchers have also spotted belugas missing circular chunks of flesh that match the gape of a Greenland shark. Like seals, belugas have to keep careful track of ice-free water in the wintertime so they can breathe. Caught between sharks and suffocation, it seems, some whales will chance becoming an hors d’oeuvre for a breath of fresh air.