September 23, 2020

The oceans can feed a billion people, but who needs fish most?

BY: Emily Nuñez

Sardinella has long been a staple food in Senegal. The herring-like fish, known locally as yaboy, plays such an integral role in local diets that it’s one of the ingredients in Senegal’s national dish, thiéboudienne: fish with rice and vegetables, simmered in tomato sauce. When it’s not eaten fresh, it’s soaked in brine and dried, then trucked to inland parts of Senegal and other West African countries, where ocean-caught fish are an essential source of animal protein.

This little fish is cheap, too – or at least it used to be, before the foreign-owned fishmeal factories arrived and started buying up sardinella at prices the locals couldn’t afford. Once the sardinella are taken to a warehouse, dumped down a chute, and pulverized by high-powered blades, the resulting powder is exported to wealthier countries – often China – and fed to carnivorous farmed fish and pigs.

This has a reverse Robin Hood effect: Sardinella are taken from the poor to feed the rich, with the potential for catastrophic consequences. Senegal’s waters are already susceptible to overfishing and climate change-related impacts, which could further hurt fish stocks and the millions of people reliant on oceans.

“This deprives poorer people of previously affordable, nutritious fish, while producing costly farmed fish that are then largely consumed by people in the rich West or in East Asia,” fisheries scientist and Oceana Board Member Dr. Daniel Pauly said. Even worse, this process creates a net protein loss for the planet. So when we say fish is good for “us,” Pauly explains, we need to ask who exactly is reaping these benefits.

To tackle this tricky question, Oceana has begun exploring an expansion of its “Save the Oceans, Feed the World” initiative to focus not just on the countries catching the most fish, but also on the people who need fish the most.

What is food security?

Support Oceana long enough and you will hear this statistic: Nearly 90% of the world’s wild fish catch comes from the national waters of just 29 countries and the European Union. It’s the driving force behind Oceana’s country-by-country approach, as well as the Save the Oceans, Feed the World initiative that launched in 2013 with the impetus to rebuild ocean abundance. Since then, Oceana has won over 100 victories and expanded its work to several new countries, including Brazil, the Philippines, Peru, Canada, and Mexico.

But as we’ve seen in Senegal, fish are not always eaten where they’re caught. Oceana’s new efforts – colloquially dubbed Save the Oceans, Feed the World 2.0 – are exploring a more nuanced discussion of the links between fishing, nutrition, and food security.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, there are four pillars to food security: availability, access, utilization, and stability. Dr. Katie Matthews, chief scientist at Oceana, explained, “Availability is whether or not there is food to be eaten, access is whether you can get that food for yourself or your family, utilization is whether you can prepare it in such a way that it nourishes your body, and stability is consistency across those previous three dimensions.”

The original framework primarily addresses the “availability” pillar, but what about the others? Matthews said that while Oceana is still focused on ensuring there is fish to be caught, they are also analyzing opportunities to prioritize work on fisheries that are most essential to local nutrition, food security, and livelihoods.

“We want to give more consideration to access,” Matthews said. “For example, rebuilding a fishery that supports an offshore foreign fleet which sends all of its catch abroad and doesn’t improve the food security of nearby coastal communities is not going to be helpful in this framework.”

Crunching the numbers

The connection between fishing and food security is often murky, but recent studies have shone a light on the subject. A 2019 study led by Dr. Christina Hicks found that a little bit of fish can go a long way, provided that it’s sold and consumed locally. In Namibia, 9% of the country’s annual fish catch could supply the entire coastal population – nearly half of which is iron-deficient – with enough iron. And in the South Pacific, just 1% of Kiribati’s catch could provide all children under five with a healthy helping of calcium.

The problem, then, is not a lack of fish – it’s where the fish end up. “Nutrient surpluses of some coastal countries in which nutritional needs are not being met highlight that large yields do not necessarily lead to food and nutrition security,” Hicks and other authors wrote in their paper, published in the journal Nature last September.

Global demand for fishmeal is just one reason why seafood might not be eaten by the most vulnerable populations. Others may include food waste within the supply chain, economic or physical barriers to access, the stipulations of international trade deals, and foreign fleets that plunder other countries’ waters.

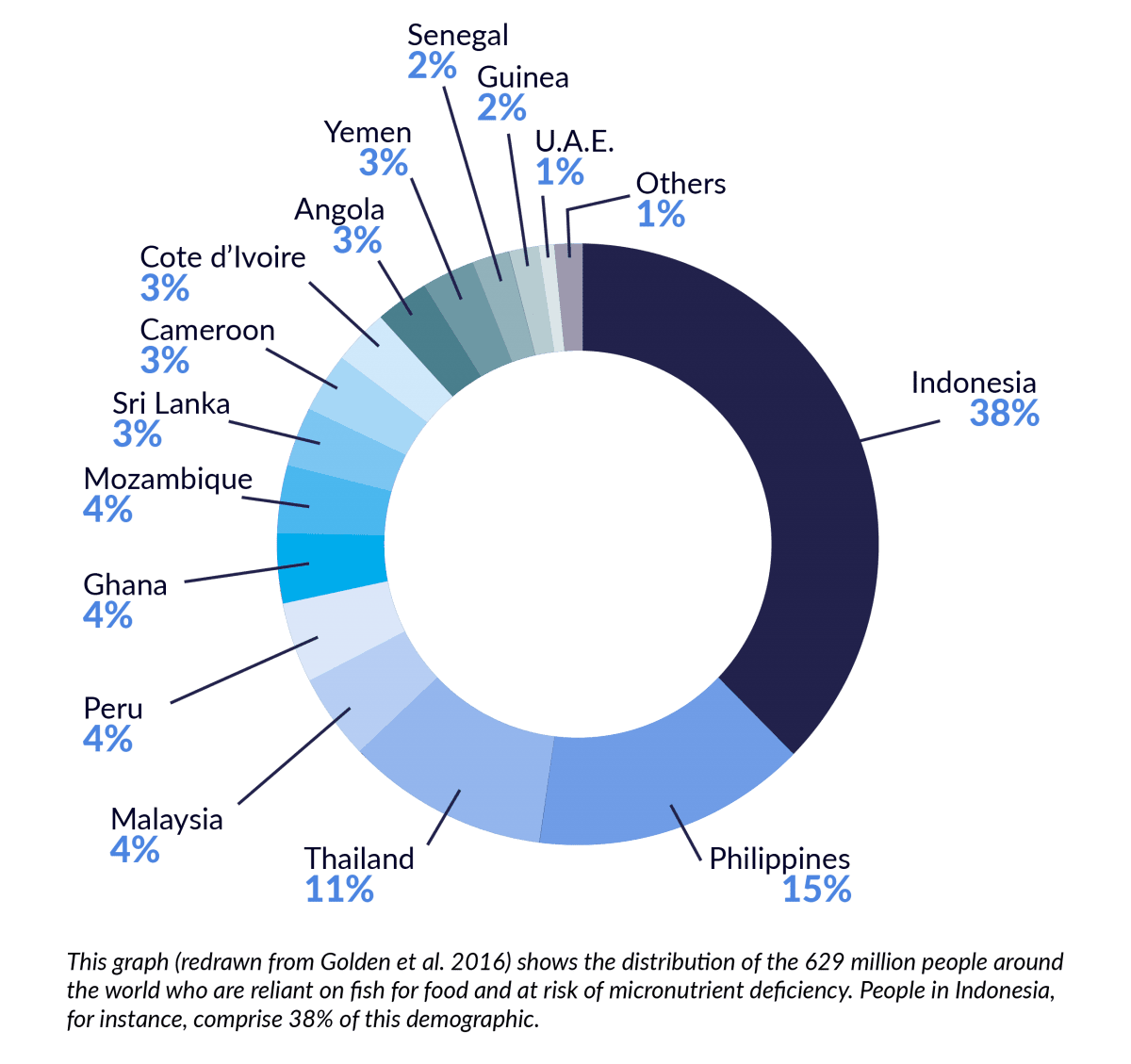

This partly explains why 629 million people around the world are both reliant on fish for food and vulnerable to micronutrient deficiencies, according to a 2016 study led by Dr. Chris Golden and co-authored by Dr. Eddie Allison, both Oceana Science Advisors. Some key differences emerge when you compare the list of the top fishing nations – used in the Save the Oceans, Feed the World 1.0 framework – to the list of countries with the most people reliant on fish and vulnerable to their loss (shown in the graph below).

For example, although Indonesia is second to China in terms of seafood catch, it tops the latter list where fish dependence and nutrition are concerned. The latter list also includes countries not among the top fishing nations globally, such as Senegal, Mozambique, and Sri Lanka.

‘Feeding the world’ in action

Right now, 821 million people around the world are living in hunger. This crisis is likely to escalate, with the population projected to grow by 2 billion people over the next 30 years. But by ensuring that fisheries are managed sustainably, and by protecting vulnerable habitats, wild-caught fish can help chip away at global hunger.

A recent paper by Dr. Carlos M. Duarte and a team of marine scientists from 10 countries highlighted past ocean recoveries. Using history as a guide, scientists estimated that much of the world’s oceans could be restored within 30 years. Oceana Science Advisor Dr. Boris Worm (also featured in a Q&A interview here) was one of those authors. He said he was surprised to see how quickly and strongly some species and ecosystems have bounced back.

“One example is the recovery of fishery resource species on Georges Bank, after half of it was closed to fishing in 1994,” Worm said. “The results for scallops and haddock, for example, are quite spectacular and demonstrate the resilience that is inherent in many ocean ecosystems even today.”

From the beginning, Oceana’s Save the Oceans, Feed the World initiative has stressed that 1 billion people could be given a healthy seafood meal every day if we protect and restore the ocean’s resources.

Going forward, Matthews said the key to success will be determining how these resources can be delivered to the people who need them most. “The world can no longer continue to ignore the role that marine fisheries play in food security and nutrition for more than 700 million people around the world,” Matthews said. “We must ask how fisheries can better serve local communities.”

This story appears in the current issue of Oceana Magazine. Read it online here.