August 24, 2017

Offshore oil exploration kills the tiny critters that whales need to eat

BY: Amy McDermott

Life in the ocean is no picnic. But if it was, then little animals called zooplankton would be potato salad. They’re the classic dish that feeds everything from fish to whales. It’s scary to think about these essential prey disappearing. But according to a recent study, oil and gas exploration could kill huge swaths of zooplankton, taking food from everybody else.

The study, published this June in Nature Ecology & Evolution, was the first to probe the effects of seismic airgun blasting on wild plankton across large distances. During seismic blasting, bursts of compressed air are fired into the seabed to identify potential fuel reserves. Those blasts can kill zooplankton for at least a kilometer (0.6 miles) around test sites, the new study found. What that means for fish and whales is still unclear, experts agree, but it could have crippling consequences higher up the food chain.

“These small animals underpin everything else in the ocean,” said marine scientist Robert McCauley of Curtin University in Perth, Australia, who led the new study. “You can’t go around creating large-scale effects without understanding what’s going on.”

Cause for concern

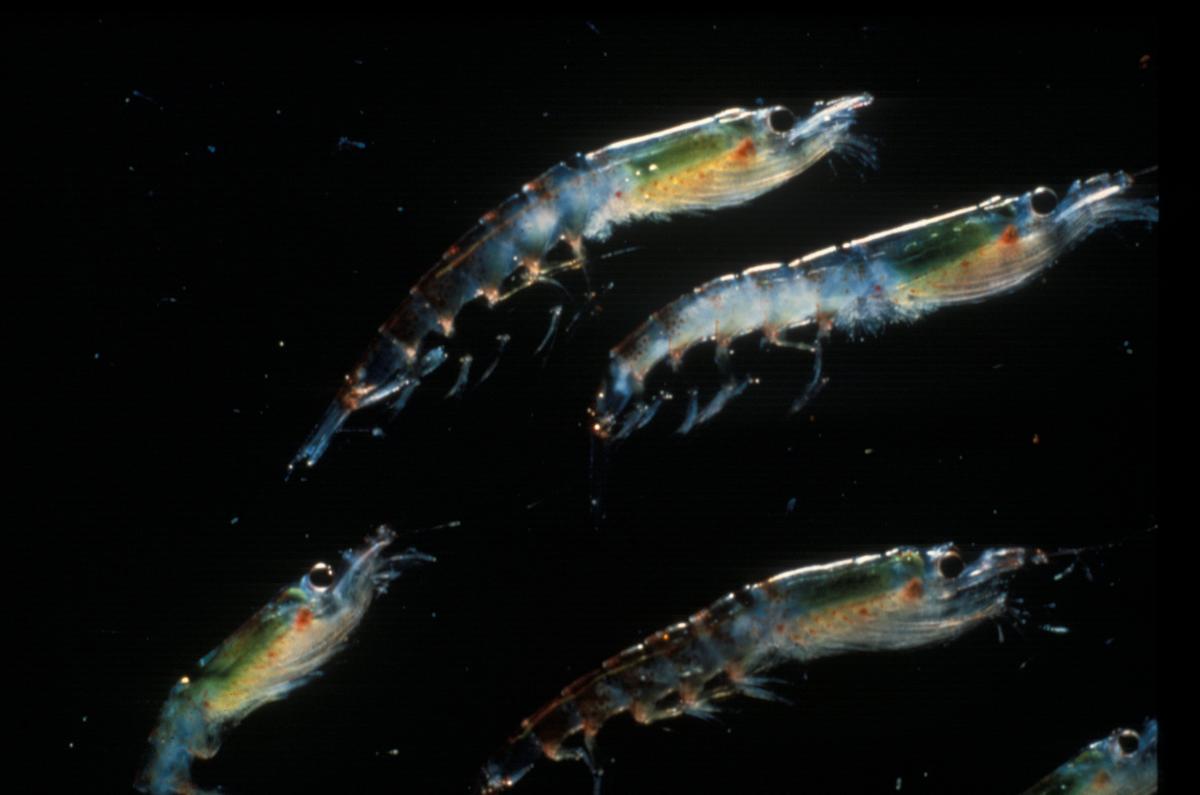

Zooplankton is a catchall term for any animal that drifts at sea, and can’t successfully swim against a current. The word is taken from the Greek for “wandering animals.” There are at least 7,000 species that voyage this way for their entire lives.

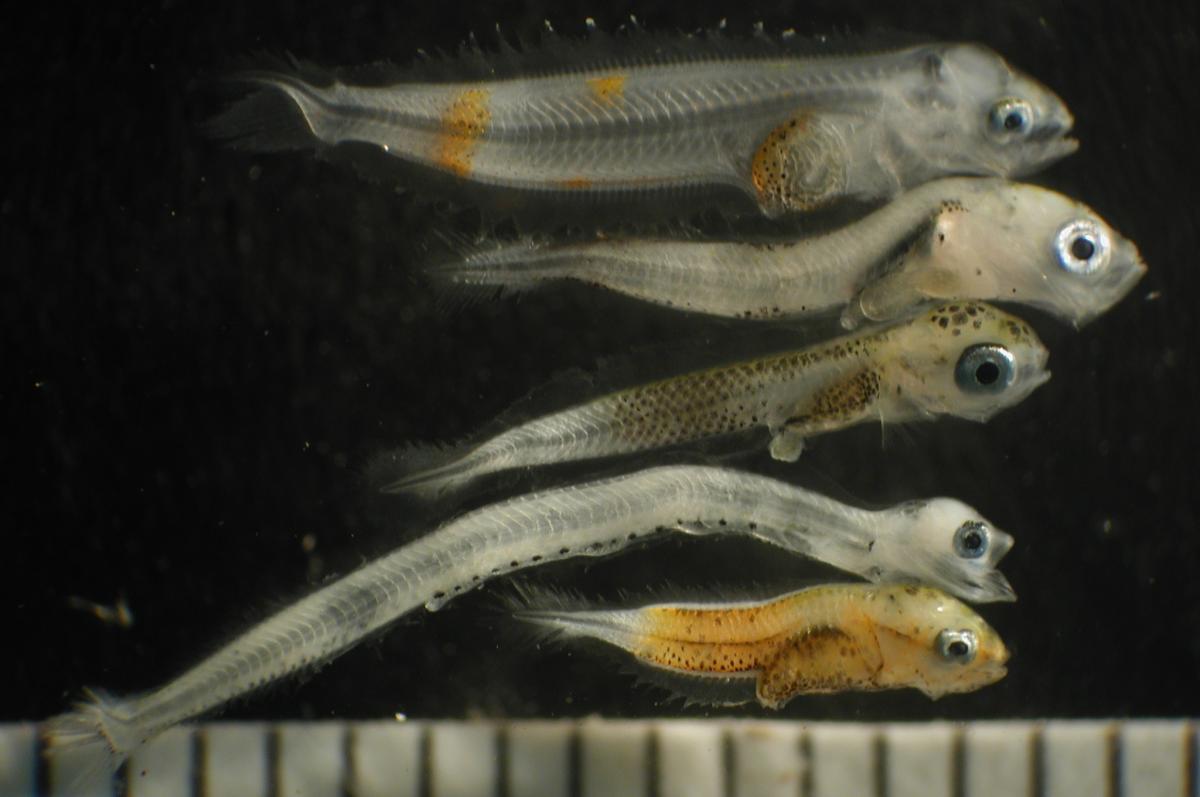

Small shrimp-like krill are perhaps the most famous example. Swarms of the pink crustaceans feed baleen whales, fish and seabirds. Other planktonic animals include tiny baby fish and shellfish, which begin their lives afloat but don’t stay drifters forever. Black marlin start out as small, relatively helpless zooplankton. But as adults, they can weigh more than 1,000 pounds and accelerate to 80 miles per hour, faster than any other fish. Lobster and oysters also go through a plankton phase, before they settle out of the water column.

Krill and baby fish are pretty small, but not all plankton are so little. Drifting invertebrates called siphonophores can grow more than a hundred feet long; these plankton are the longest animals in the world.

The opposite of plankton is nekton. Whales, dolphins, turtles, fish and snorkelers are all examples; they can go against the flow. Compared to nekton, most zooplankton aren’t relatable. Some don’t even have a face. But what they lack in charisma, zooplankton make up in worth. They are lunch for small fish like anchovies, herring and sardines, which ultimately feed bigger fish, marine mammals and sharks. Without the foundation of the food chain, bigger creatures wouldn’t be here either.

“People don’t necessarily stop and think about the importance of plankton,” said ecologist Jayson Semmens of the University of Tasmania, who also worked on the new study. “A lot of people know that whales eat tiny crustaceans,” he said. “But, what they don’t understand, is that everything does. It’s where it all starts.”

Losing plankton would be bad. Scientists already had evidence that low-frequency airgun blasts can affect other animals. Blasting interferes with essential whale and dolphin behaviors, like communication, feeding and breeding and can also displace fish and reduce catch rates of some commercially important species. But it wasn’t clear if seismic had far-reaching consequences for zooplankton.

McCauley’s team dug into that question with experiments off Southeastern Tasmania. For two days in March 2015, the scientists towed airguns behind their boat, and collected netfuls of wild zooplankton before and after the guns were fired. Before testing, 19 percent of zooplankton were naturally dead, on average. Thirty-two percent more died after the tests, including baby krill and small crustaceans called copepods, which had been alive before testing. The death toll spiked, then stayed high for at least a kilometer from the boat, as far out as the researchers surveyed.

Besides dead plankton, McCauley’s team reported other evidence of seismic impacts too. They found 64 percent fewer zooplankton in the water after testing, and apparent holes in the layer of plankton that normally blankets sunlit surface waters, detected by sonar.

The new results are noteworthy, but they don’t prove an impact yet, said Anthony Richardson, a zooplankton ecologist with Australia’s federal ocean research agency CSIRO and the University of Queensland, who was not involved in the new study. He’d like to see more experiments and samples before calling anything definitive. The zooplankton study is “suggestive rather than conclusive,” Richardson said. “But it’s quite concerning if it is true.”

Less plankton, more problems

If seismic testing does kill plankton, the sudden die-off might draw predators in at first. But feast could turn to famine, Richardson said, if the zooplankton populations don’t bounce back quickly.

In response to the recent study, Richardson used computers to scale up the results and predict how airgun blasting might affect plankton populations over larger areas. He found that plankton would probably rebound quickly in the tropics, but cautioned that “we don’t know how they’re going to recover.”

Concerns in Tasmania translate elsewhere in the ocean. Even though the plankton species are different, they are physically similar, and would probably respond similarly to seismic blasting too, McCauley said. “In general,” he said, “you would expect the results are transferrable.”

Zooplankton are the base of the food chain that feed fish and whales — and ultimately people too. Lobsters and oysters are just two commercial species that start life as larvae drifting in the currents. If seismic airgun blasting led to a decrease in abundance of popular food species like these, it could be bad for fishermen too. Despite the concerns this new study raises, it didn’t get much attention back in June. A few news outlets covered it, but not enough, said fish and whale researcher Trevor Branch of the University of Washington. “I just don’t think people appreciated how big the impact could be,” he said.

Zooplankton are the base of the food chain that feed fish and whales — and ultimately people too. Lobsters and oysters are just two commercial species that start life as larvae drifting in the currents. If seismic airgun blasting led to a decrease in abundance of popular food species like these, it could be bad for fishermen too. Despite the concerns this new study raises, it didn’t get much attention back in June. A few news outlets covered it, but not enough, said fish and whale researcher Trevor Branch of the University of Washington. “I just don’t think people appreciated how big the impact could be,” he said.

These important creatures underpin marine life in more ways than one. Zooplankton are quite literally in the ocean’s bedrock. Over hundreds of millions of years, their bodies decomposed into fossil fuels, Richardson explained.

Ironically, oil and gas were once zooplankton adrift at sea. And, as this new study shows, seismic airgun blasting to find those fuels may threaten the very creatures that made them.