December 11, 2017

Quantity or quality? When it comes to babies, healthy corals don’t compromise

BY: Marah J. Hardt

We are taught that we have to choose: quality or quantity. A company can manufacture a limited number of luxury products or mass-produce an endless supply of cheap ones. A restaurant can go for a five-star rating serving select clientele or go the fast-food model, banking on high turnover rather than taste.

Good thing for the oceans, coral reefs never got that memo. Instead, according to an October study in Conservation Letters, scientists discovered that some corals make more babies than others, and these super-parent corals can do so without compromising the quality of their offspring.

“It was really surprising how many juveniles the healthy corals were able to make,” said study co-author Kristen Marhaver, a reef biologist at Curacao’s CARMABI Foundation.

By studying the corals on healthy and degraded reefs off the Caribbean nation of Curacao, the researchers found that the power to pump out loads of high-quality larvae appears to be linked with the overall health of the reef. This means the world’s remaining pristine reefs may deserve more protections than we realized.

“Even a small, healthy reef,” Marhaver said, “can make a big difference.”

Makin’ coral babies

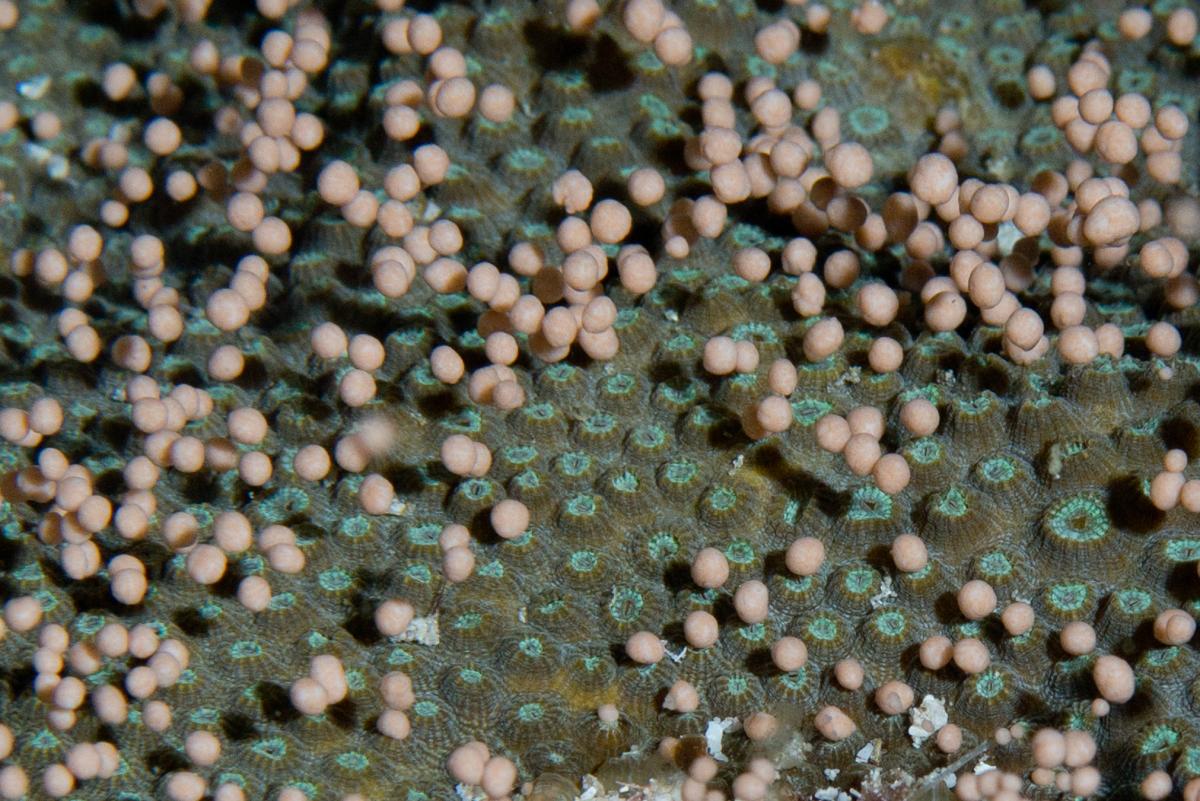

When you can’t move to mate, sex can be a challenge. Corals overcome this predicament through multiple strategies. Many large, reef-building corals engage in synchronized sex via mass-spawning. Nearly celibate for life, these hermaphrodite corals coordinate the release of millions of sperm and eggs into the sea for just two or three nights a year, turning the waters into an underwater blizzard of coral spawn.

Other coral species reproduce in a less-extroverted manner. Called “brooders,” these species may have separate sexes or be hermaphrodites. They release sperm into the water, which is then collected by other brooders. Fertilization happens within the protected fold of the coral’s soft body parts, where tiny larvae can grow larger before being released into the wild. Some brooders spawn year-round while others have seasonal peaks.

Both methods of reproduction produce miniature larvae that one day grow to form some of the largest living structures on earth. “Pretty much every year I look at a cohort of teeny coral larvae and think: There’s no way those things can grow to be 500 years old,” Marhaver said. ”But they can! Every year I’m fascinated all over again.”

Corals’ secret sauce

To understand what distinguishes healthy reefs from degraded ones, scientists examined the abundance of a particularly precious resource on the reef: fats, also known as lipids.

Normally, reef health is measured by the amount of living coral in a given area. But coral offspring “are almost entirely made out of lipids,” said Aaron Hartmann, the study’s lead scientist. “So it got us to thinking that perhaps corals with more lipids would produce more or larger babies.”

While humans try to cut fat from our diets, in corals, the more fat the better — for offspring and their parents. Fat-rich parents can give more energy to their larvae, which leads to higher-quality babies. More lipids also benefit adults, by helping them withstand climate change related stresses like dangerously hot temperatures.

So, fats are important. To see just how important they are, Hartmann and his colleagues compared two reefs on Curacao: a sickly one off the port town of Willemstad, and a robust one off Oostpunt, on the undeveloped eastern end of the island.

The scientists discovered that brooder corals on Oostpunt produced up to four times as many babies as Willemstad corals of the same species. The healthy reef also had a higher density of parent corals overall.

As a result, Oostpunt churned out up to 200 times more coral babies per square meter than its degraded counterpart. Despite the dramatic difference in the number of babies between the two reefs, the size and quality of the offspring was the same.

Normally, we would expect a trade-off between the number and quality of offspring, due to resource limitation. But this study revealed that adult colonies on healthy reefs had higher fat stores than colonies on degraded reefs. So, adults from healthy reefs simply made more, equally-fit larvae.

Size isn’t everything

Coral reefs are one of the most threatened ecosystems on the planet. Dangers range from overfishing to climate change. Effective conservation requires that we understand and value the world’s remaining reefs accurately, especially when we weigh trade-offs between the development of local human communities and long-term ecosystem health.

Judging a reef by how much of it is covered in living coral underestimates its value. “A reef that goes from 40 percent to 20 percent cover isn’t losing 20 percent of value,” Hartmann said. “It’s losing a lot more, in the form of many fewer larvae per unit of cover.” Even small areas of healthy reef may be critical sources of larvae for other reefs downstream.

The island of Curacao faces this challenge right now as it considers the impacts of a proposed massive development project that would threaten the reefs off Oostpunt. The question is, now that we know how valuable these little but robust reefs are, will Curacao protect them?