July 1, 2021

That Plastic Bottle You Thought You Recycled May Have Been ‘Downcycled’ Instead

BY: Emily Nuñez

Picture this: After tossing a single-use plastic bottle into your curbside recycling bin, it gets picked up and trucked to a material recovery facility, or MRF. Once there, it’s separated from the paper, glass, and metal and sorted into groups of similar plastics.

Your bottle – and countless others – are then packed into a rectangular bale, sold as a commodity, and sent to another facility to be sorted by color, shredded, sanitized, melted down, and molded into smaller, smoother bits of plastic called “nurdles.”

Finally, the rice-sized remains of your bottle are purchased again, melted again, and fashioned into another bottle, ready to be filled with a fruity or fizzy drink.

This example is the best-case scenario for plastic bottles, but unfortunately it is not the norm. Plastic recycling is cumbersome and expensive, and in many cases, new “virgin plastics” are cheaper than recycled plastics.

THE TRUTH

Less than 30% of plastic bottles are recycled in the U.S., but technically speaking, most are “downcycled.” Also known as cascaded recycling or open-loop recycling, downcycling occurs when a material is remade into an item of lower quality. These items typically can’t be recycled again, which cuts an item’s overall life cycle short.

While recycling closes the loop and keeps an item in circulation – just like the chasing arrows on the recycling symbol would suggest – downcycling turns that loop into a one-way arrow. From there, a material can only go downhill: After outliving its usefulness as a carpet or a bench, the next stop is the landfill or incinerator.

Even with recycling, there are limits to how long an item can circulate. The idea that our recyclable waste will be “cycled indefinitely” is a widespread myth, according to Dr. Trevor Zink and Dr. Roland Geyer.

“The belief that recycling automatically diverts material from landfill ignores the fact that, even in the most ideal recycling cases, material degrades in quality, diminishes in quantity (yield loss), or both during each use and recovery (i.e., collection and reprocessing) cycle,” Zink and Geyer wrote in a 2018 paper.

This is especially true for single-use plastics. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) – the lightweight resin commonly used to make beverage bottles – diminishes in quality when recycled. According to Zink and Geyer, these bottles are often downcycled into fiber or wood replacements instead of being recycled into new bottles.

And if a manufacturer really wants to return a used bottle to its original purpose, they might need to add virgin plastics to the mix to achieve the same quality. That’s right: You have to add new plastics to recycle old ones.

PET is one of the most valuable types of plastic, so you can imagine how difficult it is to effectively recycle other plastic resins. Industry-funded website PlasticFilmRecycling.org notes that plastic film – a material notoriously difficult to recycle – can be downcycled into composite lumber and refashioned into decks, benches, and playground sets. In other cases, plastic air pillows or grocery bags may find new life as containers, crates, and pipes.

PLASTIC WASTE BY THE NUMBERS

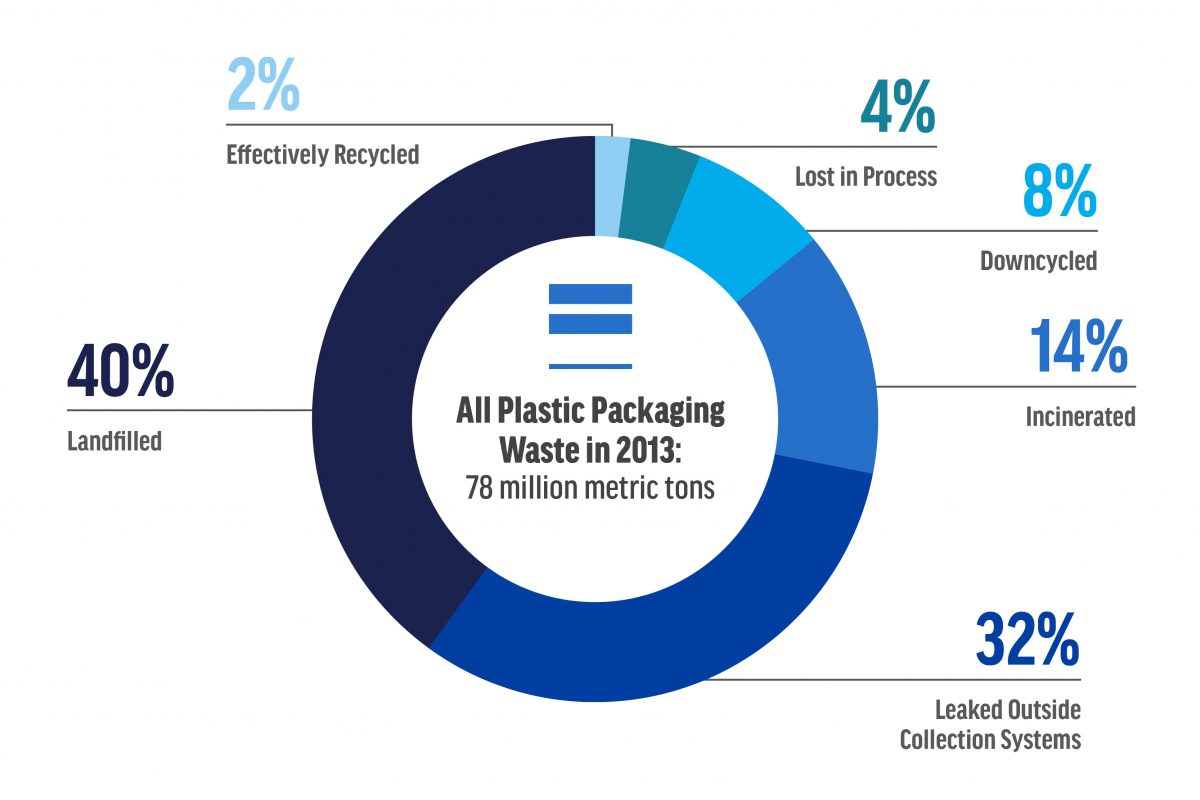

Thanks to earlier research led by Geyer, we know that only 9% of all the plastic waste ever produced has been recycled. Downcycling rates are harder to calculate, but a report by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation did just that, using plastic packaging data from 2013. The foundation found that only 14% of global plastic packaging waste was collected for recycling that year. Of that amount, 8% was downcycled and 4% was lost during the process. Only 2% was effectively recycled into a product of equal or higher value.

“Chemical recycling” is often touted as a solution by the plastics industry, but it exacerbates the climate crisis and does not curb the production of new plastics. This method, sometimes called advanced recycling, most often involves turning plastic back into fossil fuels to be burned. These technologies are unproven to work at scale and hardly qualify as “recycling.” According to the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA), plastic-to-fuel facilities release toxic chemicals into the air and overburden low-income communities and communities of color.

While downcycling is certainly better than landfilling or burning plastic (either in an incinerator or as fuel), it only delays an item’s disposal and does nothing to reduce plastic pollution. We are unable to effectively handle our plastic waste now, so picture what our oceans and landscapes will look like in 2050 when plastic waste increases fourfold – assuming current trends continue.

THE SOLUTION? REDUCE DON’T PRODUCE

But if recycling plastic isn’t a foolproof way of preventing plastic waste from piling up in landfills or polluting our oceans, then what is? Zink and Geyer offered a straightforward suggestion in their paper:

“Recycling can never prevent end-of-life disposal; it can merely delay it. This leads us to an obvious but surprisingly underappreciated conclusion: The only way to reduce the amount of material we landfill or incinerate is to reduce the amount we produce in the first place.”

Oceana agrees and campaigns to curb plastic pollution at its source. One way of doing this is by urging companies, like Amazon, to consider the environmental impact of their packaging and products. Instead of offloading the burden of recycling onto consumers, companies can offer alternatives to single-use plastics that take wasteful materials out of the equation.

Companies that sell their products in refillable and reusable containers are prime examples of market solutions to plastic pollution. Research by Oceana found that a 10% increase in the share of beverages sold in refillable bottles could result in a 22% decrease in marine plastic bottle pollution. This would keep 4.5 to 7.6 billion plastic bottles out of the ocean each year.

Governments also play a key role. Policies that limit or eliminate single-use plastics are effective at reducing the amount of pollution that makes its way into the ocean. You can help make this happen by telling your local policymakers that you support action to reduce unnecessary single-use plastics.

To learn more about how you can help protect the world’s oceans from plastic pollution with Oceana, visit our plastics campaign page.

This article is the fourth installment in Oceana’s Recycling Myth of the Month series, which highlights common misconceptions surrounding plastics and our ability to recycle or properly dispose of them. The first installment explained what those numbers on the bottom of plastic products mean, and the second explored whether plant-based bioplastics are actually better for the environment. The third explained why plastic waste is not just a “developing country problem.”