November 21, 2017

Scientists partner with puffins to study ocean health

BY: Amy McDermott

Marine biologists have a lot of high-tech tools at their disposal. But sometimes, to get the job done, they just need a puffin.

Yes, a puffin. The seabirds catch fish that would otherwise be hard to study. When parent puffins bring a meal back to nests on land, scientists briefly borrow the fish and examine them, which informs conservation efforts down the line. The whole process might sound adorable, but in practice, it’s grueling work.

In Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, for example, seabird scientists slip and slide up the wet, rocky cliffs to find puffin nesting burrows. When they find one, the scientists reach in and feel around for a load of fish. It’s a leap of faith, because you never know what’s down the hole.

“Instead of a fish in the hand, you could get a puffin bill wrapped around your fingers,” said marine biologist Bill Sydeman, the founder of California’s Farallon Institute. “Your hands get scratched up, but it’s a work of love.”

Borrowed meals

It’s not glamorous work, but pulling slimy fish out of puffins’ nests is a relatively easy way to learn about the size, length, weight and nutritional content of the fish themselves. Scientists are already out there studying the birds; why not seize the opportunity to study the fish too?

Without wild puffins, researchers would have to use boats and nets to catch the same fish species, which would be much more expensive work, and in some cases, just wouldn’t happen, Sydeman said.

Puffins are handy because they hunt for fish upwards of 100 miles around their rocky homes, he added. They also take a wide variety of species and are delicate eaters, said seabird biologist John Piatt, of the U.S. Geological Survey in Anchorage, Alaska. Tufted puffins in the North Pacific, for example (one of four puffin species in the world) feed their chicks at least 75 different species of fish and plankton, he said. That means that puffins can give scientists a fair snapshot of the fish in the area. “They bring back, we think, pretty much what’s out there,” Piatt said.

Adult puffins are also gentle with their catch. The birds carry rows of fish in their bills, rather than swallowing them. The fish are intact when the parents return to the burrow to feed waiting chicks. Whole fish give scientists the most accurate measurements of weight, length and other characteristics. And they’re nicer to work with. Just imagine if the fish were partially digested.

The size, shape and fat content of fish reveal their nutritional value. And healthier food means more healthy chicks. By tracking changes in the quality of puffins’ catches over time, researchers can also estimate how many will succeed in raising babies, year-to-year.

Puffins are useful too, because they catch fish that scientists wouldn’t otherwise survey, Sydeman said. Young fish, born in the last year, often turn up at puffin burrows. Fisheries scientists don’t typically sample fish that young by other means. But the health of those young fish is “something of an early warning,” Sydeman said, to predict how many adults will be around in a few years. Knowing how the youngest fish are faring can inform catch limits that ensure enough food for people and seabirds.

Gone fishing

This whole process is painless for the birds. “We don’t have to kill anything,” Piatt said. And when it comes to the fish, “we take very little.”

All the researchers do is set up a small cloth screen at the entrance to a puffin burrow, so the adult can’t quite get down the hole. When a parent puffin arrives home, it waddles into the nest as far as it can, drops the catch, and flies off for another round of fishing. Then the researcher reaches in, grabs the fish, measures them, then puts them back down the hole for the puffin chicks.

Reaching into puffin burrows is a modern incarnation of an ancient practice. People have used birds to get ahold of fish for thousands of years.

In the puffins’ case, the birds are not tamed. They’re not pets or trained helpers, like bomb-sniffing dogs or military dolphins. Puffins are wild birds, doing what they do naturally. Scientists just capitalize on that to study prey fish.

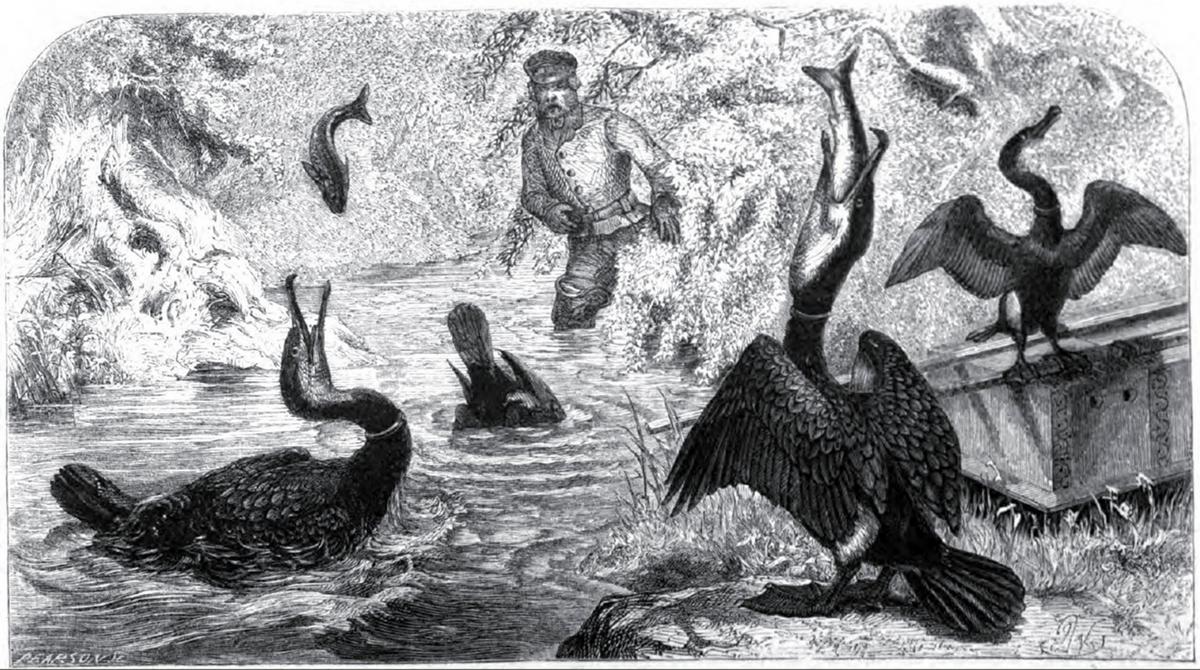

But in the past, humans have tamed birds for fishing too. As early as the 3rd century, Japanese fishermen worked with tamed cormorants that were more like pets than wild animals, said Marcus Beike, a hobby ornithologist in Germany, who published a history of the practice in 2012. It would have been a “chaotic hunting spectacle,” using multiple birds, Beike said. The practice spread from Japan to China in the medieval period, and is still used today, mostly for tourism. European kings also hunted with fishing birds, Beike added, including cormorants and osprey, in a sport like falconry.

Reaching down puffin burrows is a lot less glamorous than hunting with birds of prey. But for scientists, wild seabirds are natural allies in the pursuit of knowledge. It’s not just puffins either. In Antarctica, studies on Adélie penguin diets have helped unlock secrets of the whole food web. And in California, another black and white seabird, called the common murre, helped scientists understand that protecting rockfish populations can have rippling benefits for fisheries. If predators like murres don’t have enough rockfish to eat, they go after more commercially-important species like salmon and anchovies.

Seabird scientists have seen the potential in fish data for decades, but actually using the information is another story. “Management or policy applications are largely beginning,” said Sydeman, but they’re out there. In Alaska, for example, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration includes seabird catch data in their annual report to the North Pacific Fisheries Management Council, which sets fishing quotas for the following year.

Puffins are hardly high-tech compared to submarines and ships. But sometimes they’re the best tools for getting ocean data, plucked straight from the waves.