June 15, 2023

Sharks Under Threat

BY: Sarah Holcomb

The global trade endangering the ocean’s top predators

When a policy advisor from a United States Representative’s office arrived at Oceana headquarters in Washington D.C. the evening of the December Board Reception, he wasn’t just there to socialize. Instead, he delivered big news, fresh from Capitol Hill to Oceana’s Vice President of the U.S., Beth Lowell and her team. It was official: After years of campaigning by Oceana and its allies, the U.S. was exiting the global shark fin trade.

Leading up to the announcement, reports about whether the ban on the shark fin trade — officially known as the Shark Fin Sales Elimination Act — would be included in the soon-to-be-approved National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) changed by the day. Lowell and her team, who campaigned for this goal for nearly seven years, wanted to see the text with their own eyes. So, after the reception, they escaped to an empty local bar and scrolled the 879-page NDAA document on their phones to find the bill. “There it was,” Lowell remembers. “It felt like a scene from a movie.” Two weeks later, President Biden signed the act into law.

The U.S. has played an important role in the shark fin trade, even after the United States outlawed shark finning — the cruel practice of cutting off a shark’s fins and throwing it back into the water to face certain death — and required that sharks be landed with their fins attached (an earlier Oceana victory). Fins from as many as 73 million sharks end up in the global shark fin market every year. And, until now, shark fins were still legally bought and sold in many U.S. states.

“Almost two decades of work at Oceana has focused on protecting sharks,” Lowell says. Oceana’s campaigns have targeted shark finning — the biggest threat to shark populations’ survival. Just as the demand for ivory horns and tusks endangered rhinos and elephants, the shark fin trade endangers sharks. Nine of the top 10 shark species in the fin trade are at risk of extinction.

In 2019, Oceana and its allies successfully campaigned to ban the import and export of shark fins in Canada, becoming the first G20 nation to do so. The U.S. is now joining Canada. The new law will not only protect millions of sharks in U.S. waters; its effects will be felt worldwide. Yet this victory is hardly the end of the story. A pervasive and fraught trade for shark fins — as well as shark meat and other products — persists across the planet. And it poses a threat to sharks, ecosystems, and everyone who relies on healthy oceans.

Behind the global shark fin trade

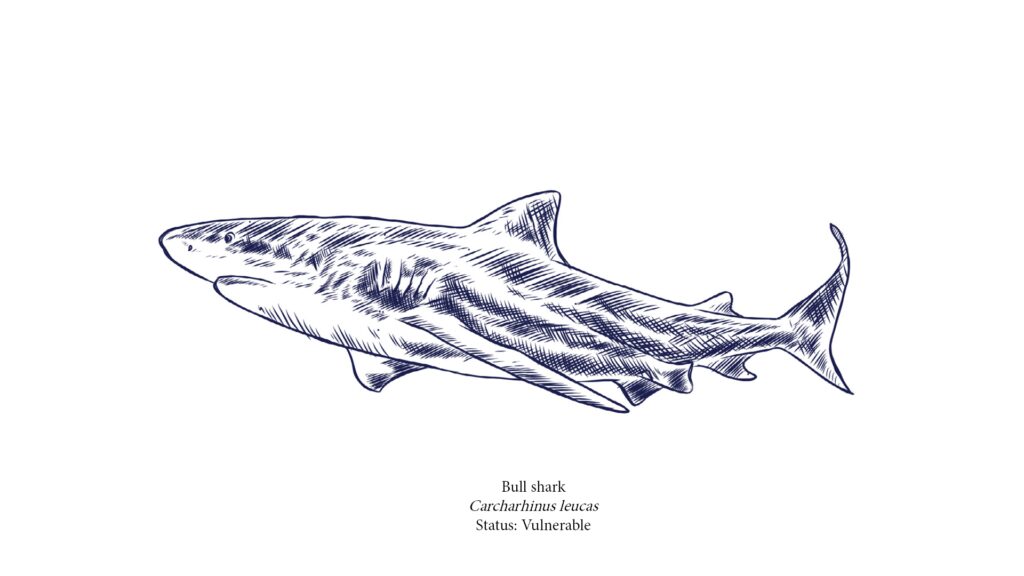

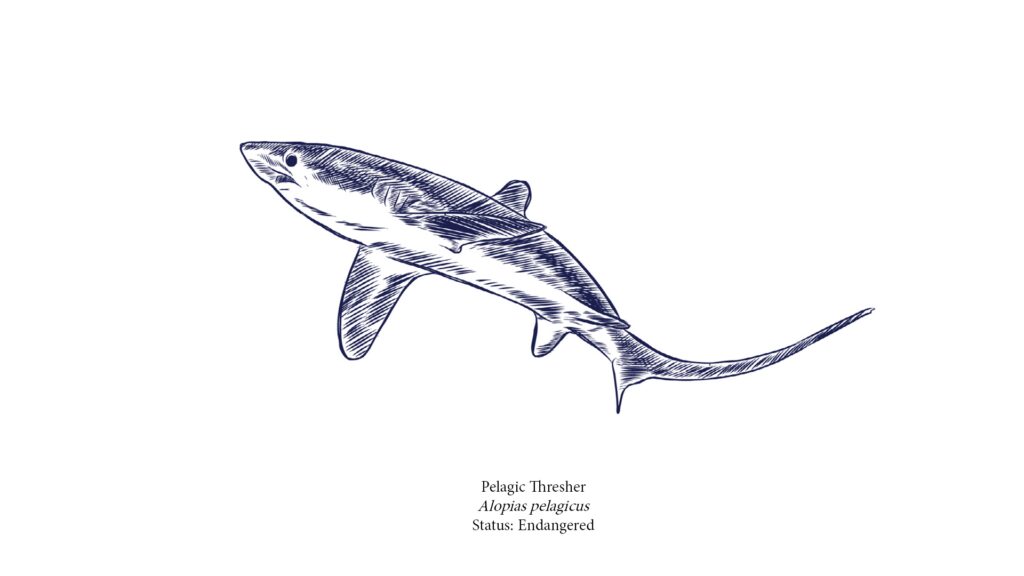

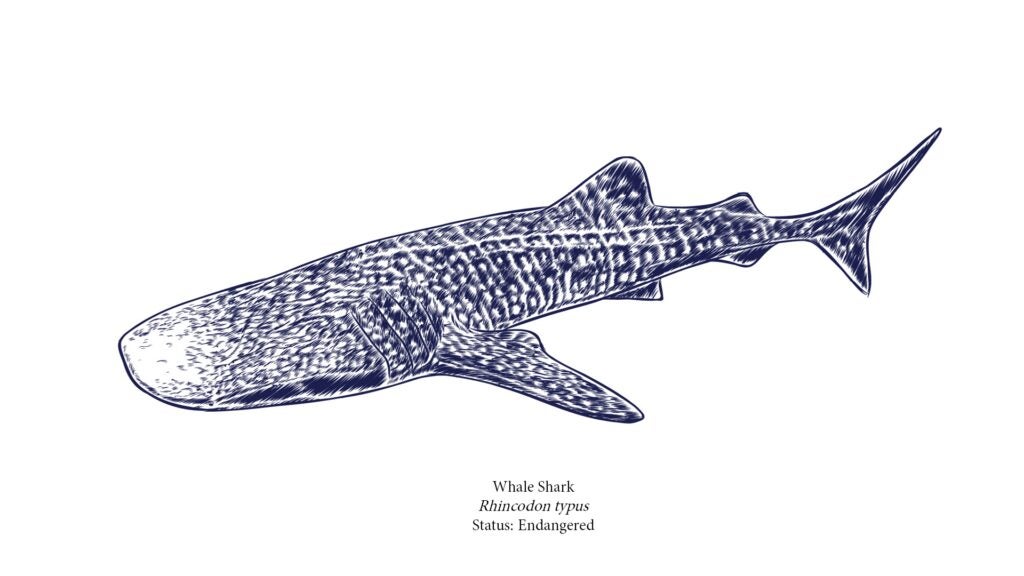

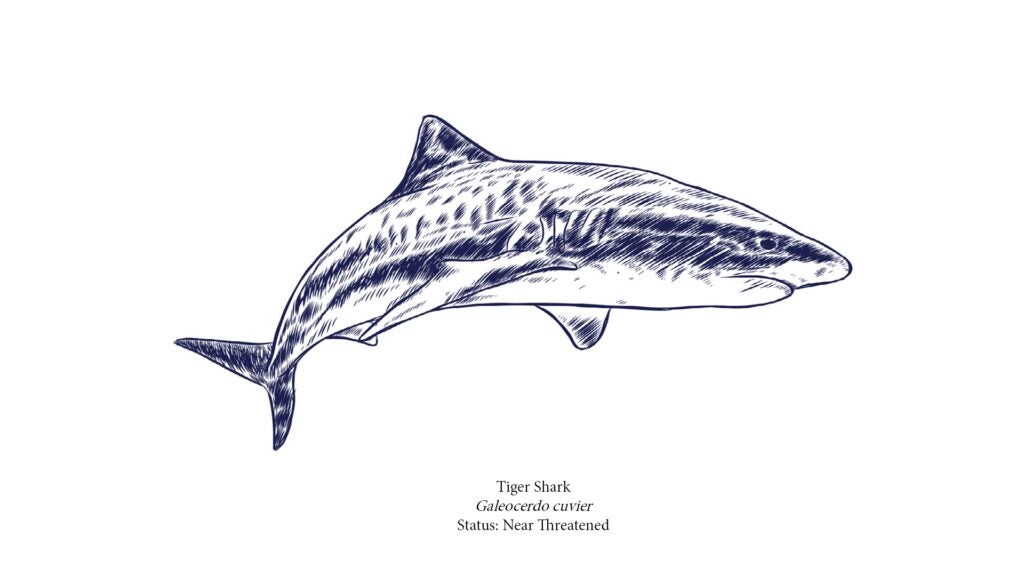

Sharks have been around for over 400 million years, even longer than trees. Today over 450 species of sharks roam the world’s oceans, from the shortfin mako shark that can swim as fast as 70 kilometers (43.5 miles) per hour and traverse entire oceans, to the graceful, slow-moving whale shark that eventually can reach the size of a school bus.

Sharks are not just an incredible assortment of species; they play a pivotal part in ocean ecosystems. Often considered apex predators, sharks keep populations in check and the environment in balance. “The oceans need healthy shark populations,” reminds Gib Brogan, Campaign Director at Oceana. Compared to other fish, sharks grow slowly and only have a few young at a time. These biological factors work in favor of the food chain, but they make sharks especially vulnerable to overfishing. Over one-third of sharks and rays are threatened with extinction, mostly due to overfishing.

While popular movies like “Jaws” have shaped the public imagination by depicting sharks as bloodthirsty monsters, it’s humans who endanger sharks, not the other way around. Globally, oceanic shark and ray populations have declined over the past 50 years by as much as 70%, according to a 2021 study in Nature. Sharks are often fished for their fins, and fins are primarily used for one thing: a sought-after delicacy known as “shark fin soup.”

Shark fin soup has long symbolized status and wealth in East Asia, tracing back over a thousand years to ancient emperors. Essentially chewy cartilage, the shark fins themselves are tasteless; it’s the broth that gives the soup its flavor. According to Chinese tradition, the fins offer health benefits. But recent studies have found fins contain mercury and methylmercury, making them unsafe for human consumption.

China is the world’s top consumer of shark fin soup, despite decreasing demand over the past decade. Demand for the soup remains strong in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Macau, and is increasingly popular in other parts of Asia including Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia, according to a 2018 report. Dried fins are stocked on market shelves, while soup is served at restaurants, weddings, and events.

Shark fin soup may not be on most menus in the United States, but the U.S. still exports shark fins to Hong Kong and China. Until now, exporting the fins has been legal; the Shark Finning Prohibition Act passed in 2000 banned shark finning in U.S. waters, not the trade of fins with other countries. From 2016 to 2022, the U.S. imported over 200,000 kg of shark fins worth nearly $1.7 million and exported over 300,000 kg of shark fins worth $4.1 million. That’s according to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) foreign trade data – the number could be higher given unreported activity.

“It’s already illegal to cut off the sharks’ fins, so it shouldn’t be legal to sell them either,” reasons U.S. Rep. Michael McCaul, R-TX, championed and co-sponsored the Shark Fin Sales Elimination Act in the House of Representatives.

McCaul and his wife Linda, an oceanographer and philanthropist, have gone swimming with sharks — an experience that reinforced to McCaul that the animals are “clearly misunderstood” and misrepresented in threatening media depictions. A documentary opened his eyes to the cruelty of the fin trade.

“I took up the bill after Rep. Ed Royce [R-CA] — who first introduced it back in 2017 — retired,” McCaul recalls. “By that point, Texas had already banned the fin trade, but our federal highways could still be used to traffic fins through the state. So I knew it was up to Congress to eradicate this gruesome practice from our nation.”

Del. Gregorio Kilili Camacho Sablan, D-MP, co-sponsored the bill in the House. Meanwhile, Sen. Cory Booker, D-NJ, and Sen. Shelley Capito, R-WV, introduced the bill multiple times in the Senate and were essential to its success. As a result of the bipartisan effort, the U.S. will no longer participate in the trade, which involves countries on nearly every continent.

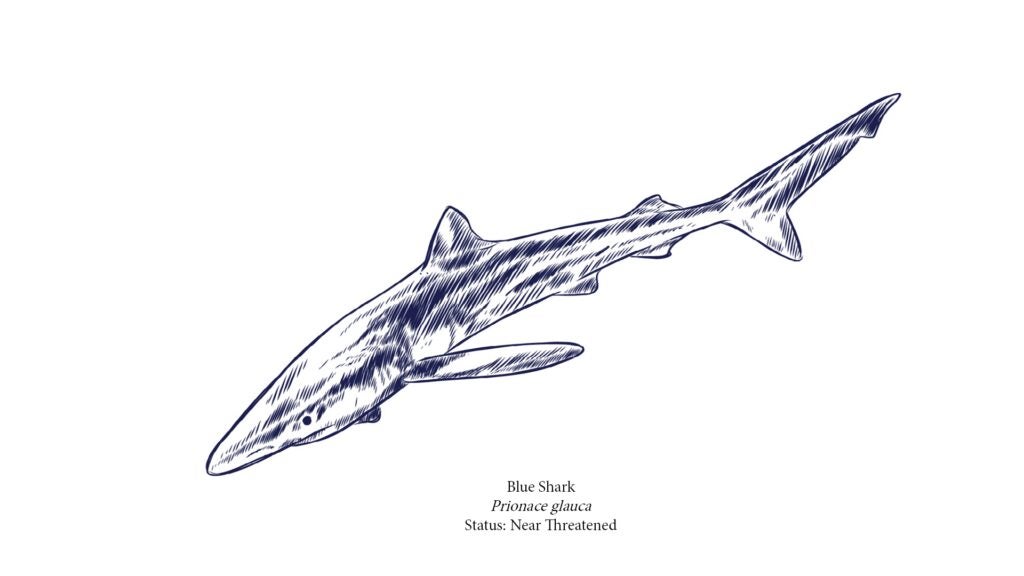

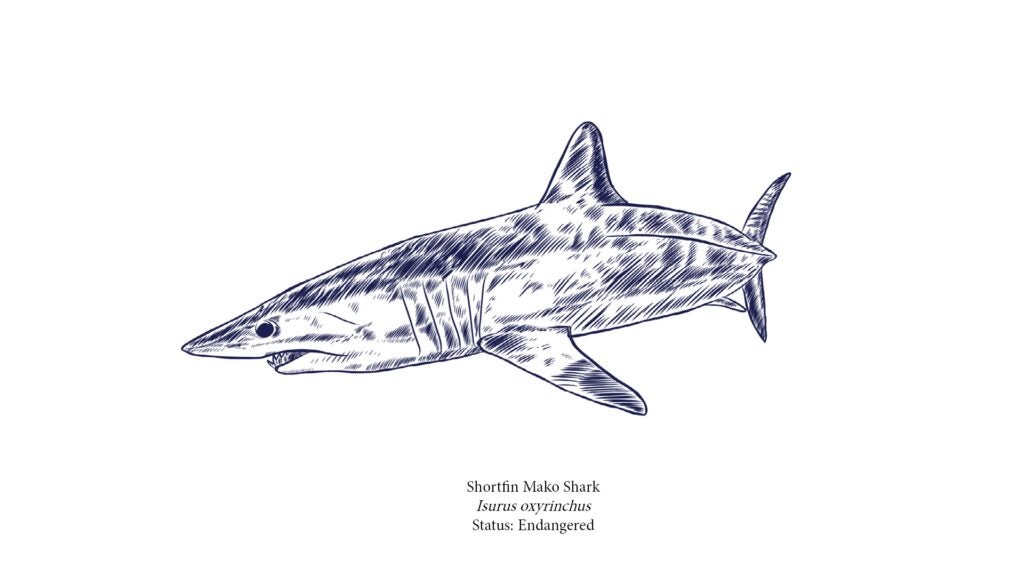

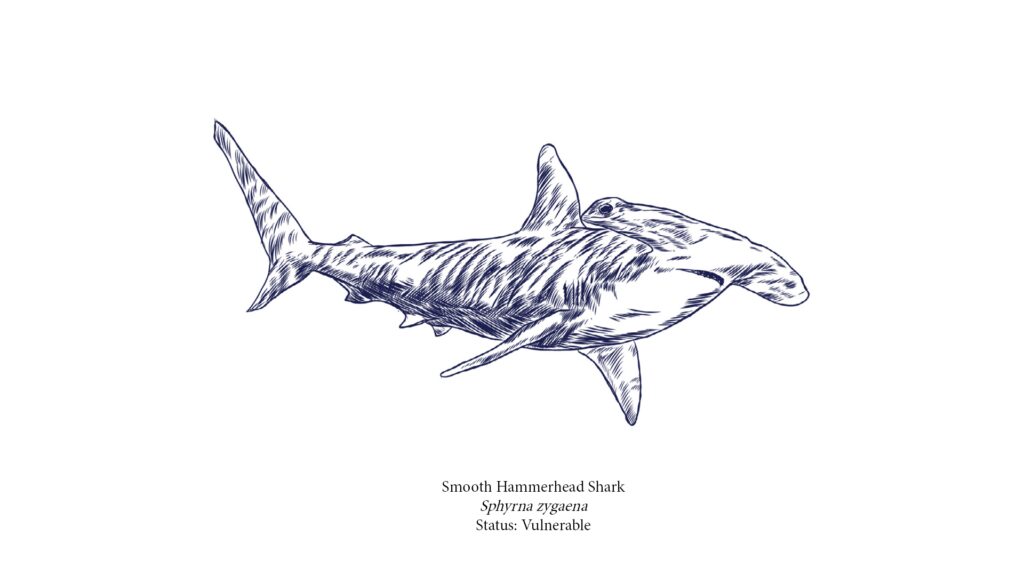

Illustrations by Alan Po

Regulations and rule breakers

In 2018, environmental prosecutors stopped a truck bound for Lima, Peru. The truck was loaded with 51 bags of wrapped shark fins — representing more than 2,000 sharks — smuggled from Ecuador. The final destination: Hong Kong.

“Today’s wildlife crimes use the same channels and mode of operating as drug trafficking,” says Dr. Alicia Kuroiwa, Oceana’s Director for Habitats and Endangered Species in Peru. “Most of the time you know there’s a criminal organization behind it.” Yet only those who were caught transporting the wildlife in Peru are typically investigated, instead of the entire chain, Kuroiwa explains.

In Peru, Oceana has been training law enforcement authorities to identify when fins are illegally traded. During the four-year investigation of the crime, Oceana helped identify the fins and found that many belonged to at least six threatened species that have trade restrictions, including the smooth hammerhead, pelagic thresher, and shortfin mako sharks. On Feb. 2, 2022, the buyer and seller were convicted in Peru’s first ever shark fin trafficking conviction.

To effectively go after these crimes in the future, though, judges and prosecutors needed better investigative tools. To access them, illegal wildlife trafficking had to be included in the Law for Organized Crime — and Oceana launched a successful campaign to do just that. The victory, secured in November 2022, empowers prosecutors with more strategies to dismantle criminal wildlife trafficking networks, like intercepting communications, working with undercover agents, accessing bank and tax information, performing monitoring and surveillance, and more.

Yet a trade of this scale cannot be fully addressed at the national level. Because laws around shark finning and shark fishing vary dramatically, with some countries banning shark finning and others putting little to no regulations in place, contraband seems inevitable. That’s why the multilateral treaty, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), exists: to protect endangered plants and animals from the threats of international trade. CITES is made up of 184 Parties — 183 countries and the European Union — that meet every two to three years and vote on regulations.

CITES lists specific “Appendices” that determine what level of protection a species will receive. Most sharks protected by CITES are listed under Appendix II. This means that in order to legally trade them, export permits are required, and the sharks must be shown to come from sustainably fished stocks.

Since the first sharks were added to the list — the basking shark and the whale shark — in 2003, many other shark and ray species have joined them. In 2019, the Parties voted to add the short and long fin mako shark, giant guitarfish, and wedgefishes to Appendix II.

But the biggest wave of shark species additions happened in November 2022, when the Parties voted to add over 60 species, including blue, tiger, and bull sharks — the most targeted by the fin trade. This groundbreaking moment means that nearly all shark species in the fin trade will be protected under CITES.

When it comes to implementing and enforcing the new CITES listings, however, challenges await.

“Once passed by vote under the CITES convention, particularly for species listed on Appendix II, there’s a lot of work still to be done. Every country must go through the legal and administrative procedures to incorporate the new listings into law, new regulations may need to be crafted, and enforcement agencies have to be trained to recognize what’s illegal,” Philip Chou, Senior Director of Global Policy at Oceana, explains.

In 2021, Kuroiwa analyzed all CITES export permit files issued by the CITES Management Authority in Peru and found that four metric tons of shark fins, representing over 5,000 sharks, were traded illegally. Sometimes traders reused supporting documents for different permits. Sometimes they used supporting documents from a species different than the one listed on the permit.

If a country does not follow regulations, CITES does have one strict measure — Article XIII — which would punish the country by closing trade for all CITES species (including everything from plants to other wildlife — not just sharks). Kuroiwa and others are in the process of appealing to Article XIII to drive Peruvian authorities to comply.

Meanwhile, outside of national jurisdictions, some shark species are swimming on the high seas. One of them, the blue shark, is the most traded shark of all.

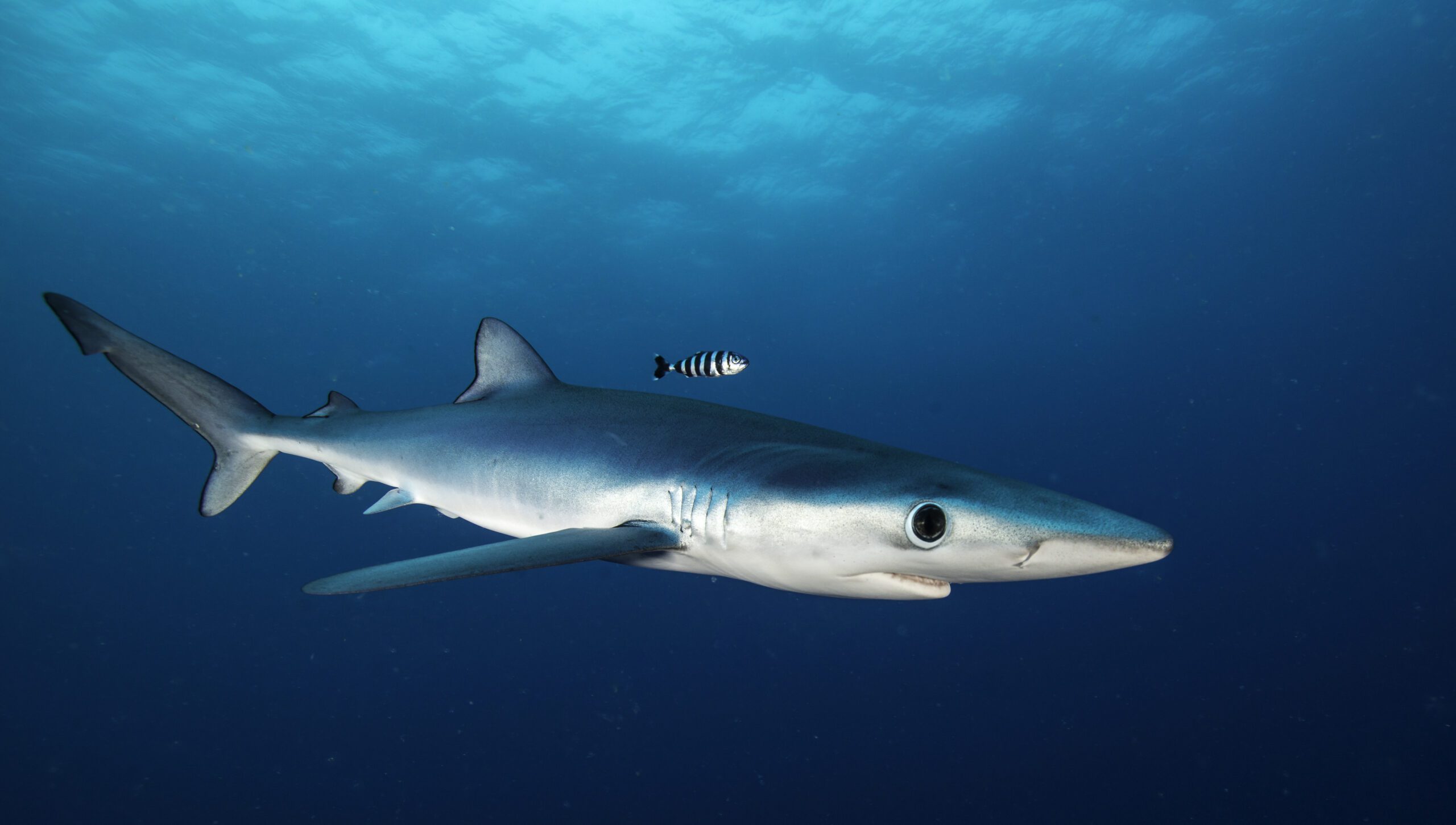

Blue sharks are not just “bycatch”

Reproducing more quickly than other sharks, blue sharks are known for their abundance and resilience. These curious, open-ocean predators are named for their unique, metallic blue backs, but it’s their long pectoral front fins that frequently make them a fishing target. The other main reason blue sharks are targeted: their meat. Unlike most other sharks, processed blue shark meat doesn’t taste too bad (we’ve been told). Often mislabeled in dishes, shark meat can even be found in pet food disguised on product labels with generic names like “white fish” or “ocean fish.”

Blue sharks not only have desirable fins and meat; they can be caught in high numbers. Blue sharks make up a whopping 60% of all reported global shark catch and 36% of all traded shark meat (an increasing market, especially in Brazil). That’s according to a first-of-its kind report on blue sharks in 2022, commissioned by Oceana. Forty-one percent of all traded shark fins come from blue sharks, and Oceana estimated the global annual blue shark catch at more than seven million individuals.

Oceana found that 90% of the blue shark catch is brought in by large-scale commercial fleets, mostly longliners, and distant-water fishing nations account for nearly three-quarters of the catch. Spain and Taiwan alone are responsible for roughly half the total catch.

The sheer volume of catch makes blue shark a high value industry. Based on data from point of sale, Oceana estimated the value of blue shark fisheries at $411 million — which surpasses that of any of the prized bluefin tuna species served at high-end sushi joints.

fisheries at $411 million. © Shutterstock/wildestanimal

Despite all of this, the blue shark is largely unmanaged. Blue sharks are fished without any limit, except for a 2019 catch limit set under the jurisdiction of the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT), a regional fisheries management organization. Tuna fisheries catch much of the blue shark as “bycatch,” but Oceana’s study found that some fleets were bringing in suspiciously more sharks than tuna — a trend that didn’t hold true for other fleets fishing in the same waters.

“For years, the fleets catching sharks have been claiming they are bycatch. This way, these fleets avoid the responsibility they have to do right by the species,” explains Oceana Chief Scientist Dr. Kathryn Matthews. “You can’t have it both ways. For too long, those commercial fleets got to have their cake and eat it too.”

If we do not change course, blue sharks could be exploited to the point of extinction. “Given these numbers, we need to put some guardrails into place now,” Chou says. Oceana’s report calls for fisheries management bodies to stop managing blue shark simply as bycatch and put in place science-based fisheries management plans specifically for blue sharks.

Since CITES recently up-listed blue shark to Appendix II, countries seeking to export blue shark internationally will need to show that these sharks come from sustainably fished stocks — hopefully catalyzing much-needed change.

Though possible — perhaps — for blue sharks, sustainable shark fisheries are elusive at best and an impossibility at worst, in light of widespread illicit activity and the fact that most shark populations reproduce and grow more slowly than other fish. Given the difficulty of implementing and enforcing regulations to keep shark populations sustainable, some countries — like Palau and Honduras — banned not only shark finning, but fishing sharks altogether.

A world without sharks

Most shark species simply cannot support ongoing commercial exploitation. And a world without sharks is a terrifying thing to imagine.

Sharks may seem “cool” or “special,” but that’s not the only reason we protect them, Matthews reminds us. “Sharks are important from a systems perspective. As awesome as they are to look at, they’re scientifically important because they’re keystone species that regulate the ecosystem… and in the absence of them, things start breaking down.”

No other fish can be cast to fill sharks’ crucial role in balancing ocean ecosystems. Declining shark populations will not only impact the health of ocean habitats already at risk from climate change and biodiversity loss; it will impact the communities who rely on a healthy ocean to survive. Saving sharks requires global protections and dedicated enforcement of them. Thankfully, it’s not too late.

© Oceana/Perrin James