December 8, 2020

Tackling a triple threat: Belize banned bottom trawling, offshore drilling, and now gillnets

BY: Emily Nuñez

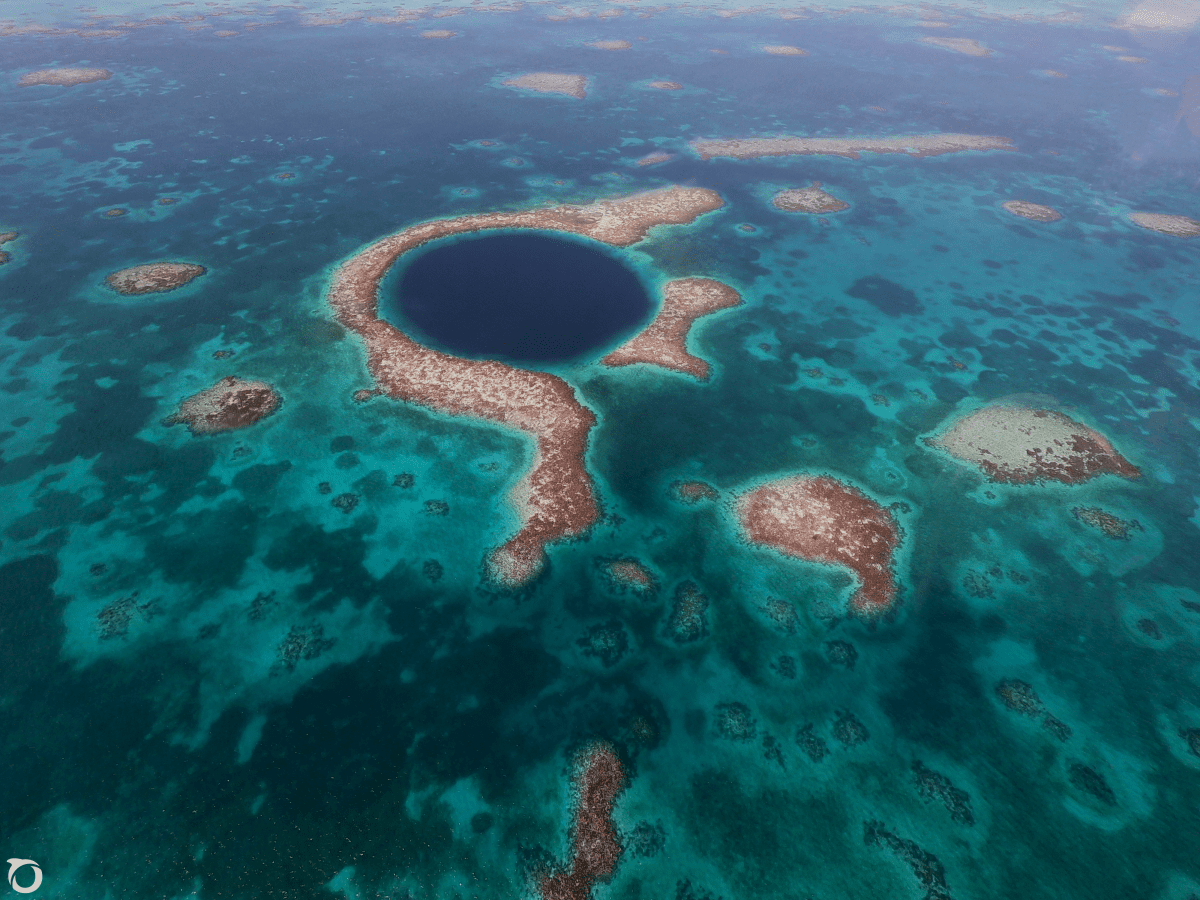

For a country that’s slightly smaller than the U.S. state of Massachusetts, Belize boasts an inordinate number of ocean wonders. It’s home to the world’s second longest barrier reef, which Charles Darwin once described as “the most remarkable reef in the West Indies.” Here, you’ll find more than 500 unique fish species – enough to give every Belizean island its own mascot and still have about 50 left over.

Because this little Caribbean country has a lot worth protecting, it has enacted some of the strongest ocean conservation laws in the world – and they just got even stronger. Following hard-fought victories that banned all trawling and offshore oil drilling in Belize’s waters, the country has now outlawed gillnets, a fishing gear that kills turtles, manatees, and many other marine animals.

In addition to implementing a nationwide gillnet ban, the Belizean government signed an agreement with Oceana and the Coalition for Sustainable Fisheries to help licensed gillnet fishers transition to other jobs. As a result, Belizean resources and livelihoods will be protected well into the future.

As Janelle Chanona, Oceana’s head in Belize, put it: “This is a historic moment for Belize, her people, the Caribbean Sea and, most importantly, for everyone who depends on the country’s marine resources for their livelihoods.”

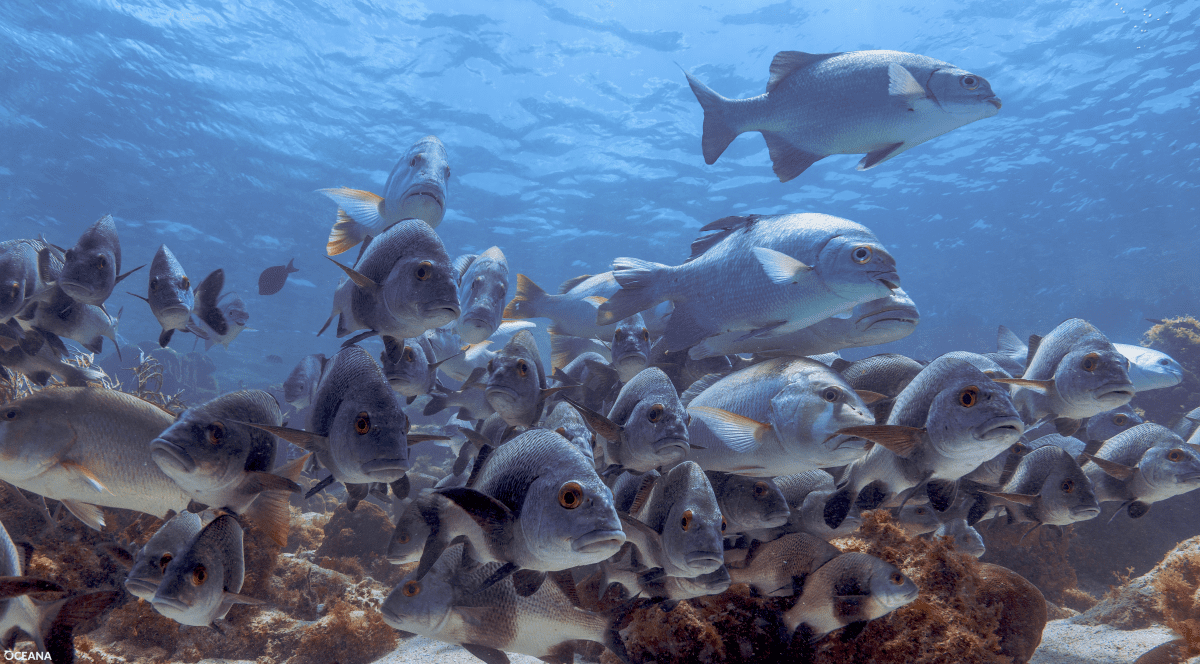

Walls of death

To say that gillnets harm marine life would be putting it delicately. The reality is far grislier. Nicknamed “walls of death,” these nets, which can measure a mile long when linked together, are indiscriminate in what they catch. They’re designed to snag fish by their opercula – the plate that protects their gills, also known as a gill cover – but they also trap non-targeted animals. Once ensnared, an animal might suffocate to death because they can no longer push air through their gills, or because they cannot resurface to breathe.

Many of these dead animals are chucked back into the ocean because they can’t be sold for profit. In Belizean waters, protected species like bonefish, tarpon, and manatees – and at least one species of endangered shark – have fallen victim to gillnets. In 2015, a rarely seen scalloped hammerhead got tangled up in a gillnet and drowned, making local headlines and sparking outrage. Gillnets have also ensnared critically endangered sawfish, a unique ray with a long snout and sawlike teeth that is said to be locally extinct.

For Lowell “Japs” Godfrey, a former gillnetter in Belize, the carnage and wastefulness were too much to bear. He handed over his net more than a decade ago and never looked back, instead switching to sustainable seaweed farming.

“With gillnets we have a lot of stuff that we just dump because we kill it, and we don’t use it,” Godfrey said. “That is one of the things that caused me to back off [from using gillnets]. I use [my vocation] not only to earn money, but to educate myself about the marine environment.”

‘Gear of choice’ for illegal fishers

Godfrey’s career change was part of a larger trend. Gillnetting has fallen out of favor, and nowadays, fewer than 100 licensed gillnetters remain in Belize. In fact, less than 3% of commercial fishers in Belize use gillnets, and some Belizean fishers have been backing a gillnet ban for more than 20 years.

The problem persists, in large part, because gillnetting is the “gear of choice” for illegal fishers, according to Chanona. Many gillnetters are coming from neighboring countries and fishing illegally in Belizean waters, then swinging by other countries’ ports to sell their catch. Doing so depletes Belize’s ocean and deprives local fishers and tourism workers of income that hinges on abundant oceans.

“COVID has reminded us that fishing-based income is more important than ever to protect,” Chanona said. “Foreign gillnetters come to their favorite fishing spot in Belize, then take all their marine products to ports in Guatemala and Honduras. Even though they are fishing in Belizean waters, none of the fruit of that labor comes through the legal economy here in Belize. Belizeans will have nowhere to fish if everything is depleted by destructive fishing practices.”

Illegal gillnetters are believed to target sharks, which are not widely eaten in Belize but are in considerable demand in Guatemala and Honduras, especially during the Catholic Lenten season when observers abstain from eating land-based animals. They are also believed to fish in marine reserves. Because these products are not processed at Belizean ports, there’s no record of what’s been removed from the ocean, potentially putting some species at risk of overfishing.

Playing by new rules

Under a Belizean law passed last year, all commercially licensed fishers must meet new requirements: They must be Belizean citizens who have lived in Belize for the last six months, and they must sell their products exclusively in Belize. Gillnetters who held licenses in 2018 must also meet these requirements to qualify for funding that would help them transition to another field of work.

Now that a ban is enacted, gillnet fishing in Belize’s maritime territory, including its Exclusive Economic Zone, is illegal and subject to penalties and fines. If anyone participating in the transition program is convicted of illegal fisheries activities, the financial support would be rescinded immediately.

But before these transitions occur, a panel of representatives from the government, Oceana, and the Coalition for Sustainable Fisheries must vet everyone who held a gillnet license in 2018. Tracking them down, however, may take a bit of detective work.

Wanted: Missing fishers

There are 83 gillnetters who are potentially eligible for the transition program. But because this list of names was compiled in 2018, some of the gillnetters have since died, and others have seemingly vanished. In September, Oceana paid to have full-page ads – containing the names of 28 missing gillnetters – placed in local newspapers.

“NOTICE,” the ad reads in big, bold letters beneath the country’s coat of arms. “The Ministry of Fisheries, Forestry, the Environment and Sustainable Development (MFFESD) is attempting to locate the following persons who possessed gillnet fishing licenses in 2018.”

The ad then lists the phone numbers of government officials who can be contacted to “discuss possible eligibility for support related to the phase-out and ban of gillnets in Belize.” A handful of responses have trickled in, but some are still nowhere to be found.

Because Belize has so many remote cayes, or islands, it’s easy for fishers to illegally enter Belize, set up camp on an island, fish to their hearts’ content, and return to a foreign port without ever encountering any authorities.

“It’s definitely strange if we can’t find someone,” Chanona said. “Belize is a small country where everybody knows everybody, and if we still can’t locate them after active questioning and investigations at the community level, that’s another indicator that they are spending the majority of their time offshore.”

Charting a new course

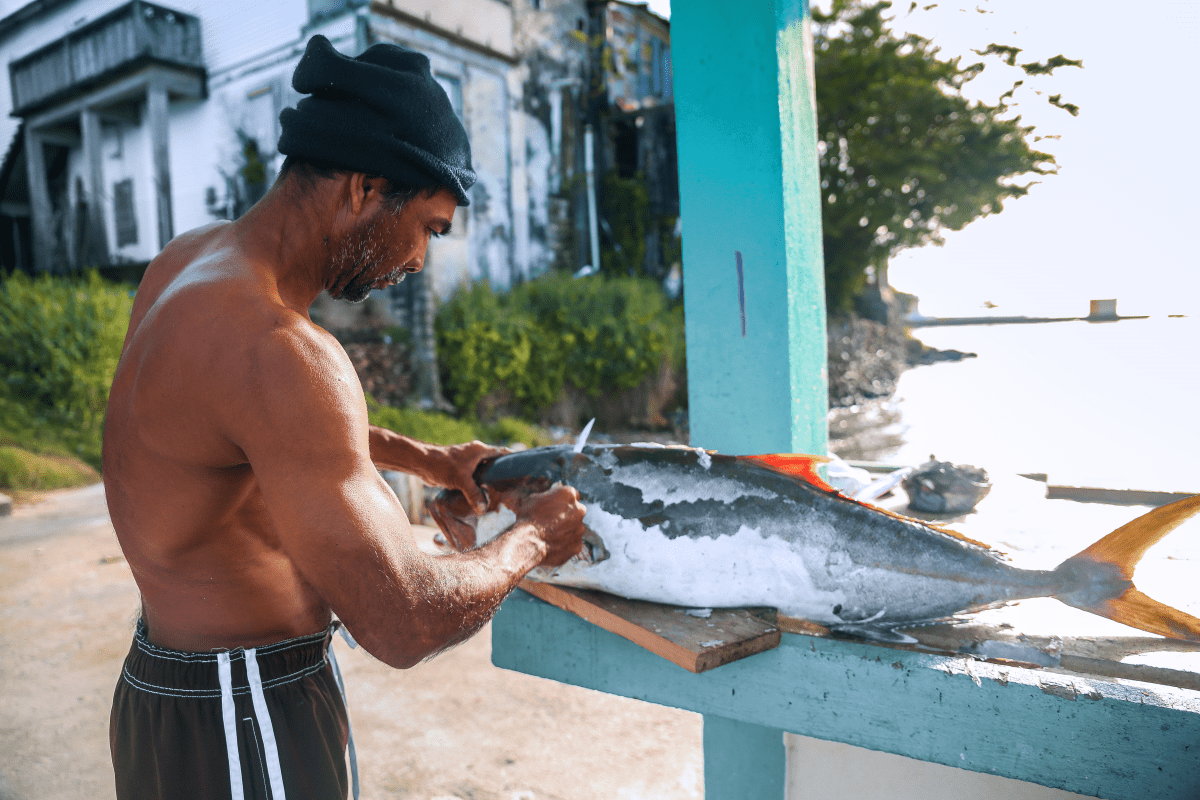

Fortunately for the legally licensed gillnetters who will be swapping out their old careers for new ones, they won’t be complete guinea pigs, nor will they be going it alone. Many Belizean fishers have already given up their gillnets – voluntarily – to protect the home that they love. Lowell Godfrey’s road to success is paved in seaweed, but many former gillnetters have also become fishing guides.

Tourism has become one of Belize’s most lucrative – and popular – industries, but the Coalition for Sustainable Fisheries plans to make a couple different career paths available to gillnetters. The Coalition, which is leading the retraining and transition process, is developing one training program for tourism and another for shrimp fishing. The latter would teach fishers how to use small traps – a far cry from the harmful trawls that industrial fishers use (the likes of which have been banned in Belize).

When all is said and done, fishers will have new vocations that not only provide income, but also instill pride and maintain their dignity as providers for their households, Chanona said. As stewards of Belize’s ocean, they will be doing their part to protect and preserve it for future generations.

“This is as much a victory for Belize as it is a testament to the perseverance of the local fishers who have overwhelmingly opposed this destructive fishing gear for decades,” Chanona said. “Every law, policy, or regulation that protects Belize’s marine resources is a win for the tens of thousands of Belizeans who depend on those resources for their food, their jobs, and their way of life.”

This story appears in the current issue of Oceana Magazine. Read it online here.