October 4, 2022

The ‘paper park’ paradox

BY: Emily Nuñez

The Wadden Sea is a diamond in the rough. Bordering Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands, it is home to seals, porpoises, about 50 species of wintering birds, seagrass meadows — and a whole lot of mud. Wadden means “mud flats” in Dutch, and many locals take meditative “mud walks” along the intertidal zone, which contains the world’s largest unbroken system of sand and mud flats.

It turns out that these mud flats foster a rich array of life — from shellfish to flatfish — and play an important role in the “transitional zones” that connect land with freshwater, and land with sea. Because these unique features lend themselves to high biodiversity, almost the entire sea has been placed under a marine protected area (MPA) status. Much of this sea is also a World Heritage Site, with the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declaring its productivity to be among “the highest in the world.”

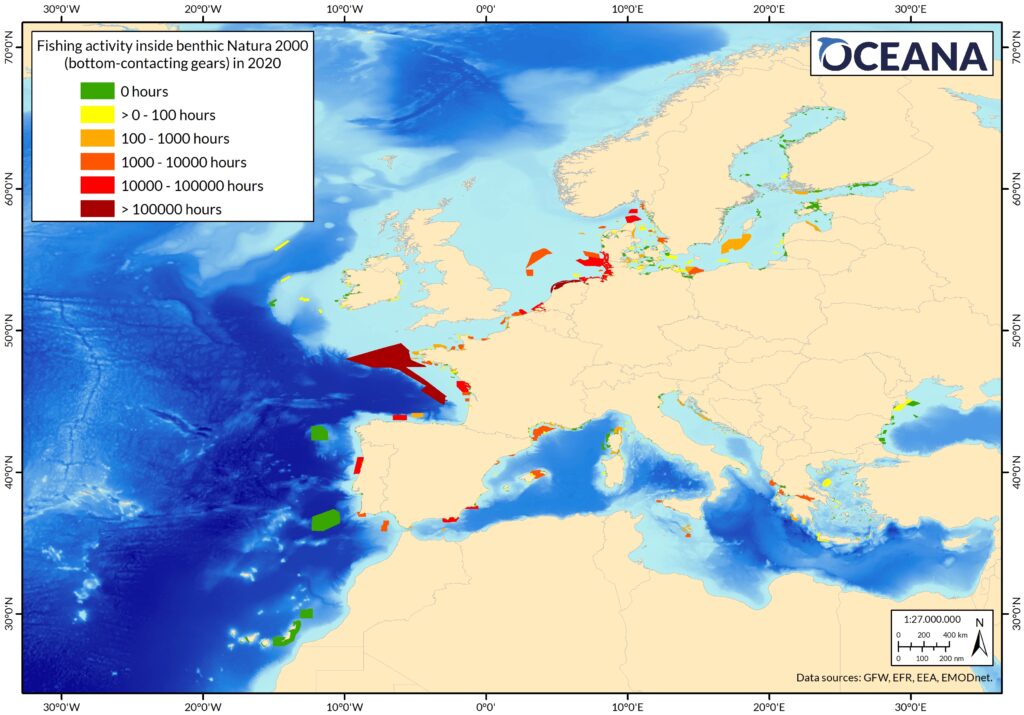

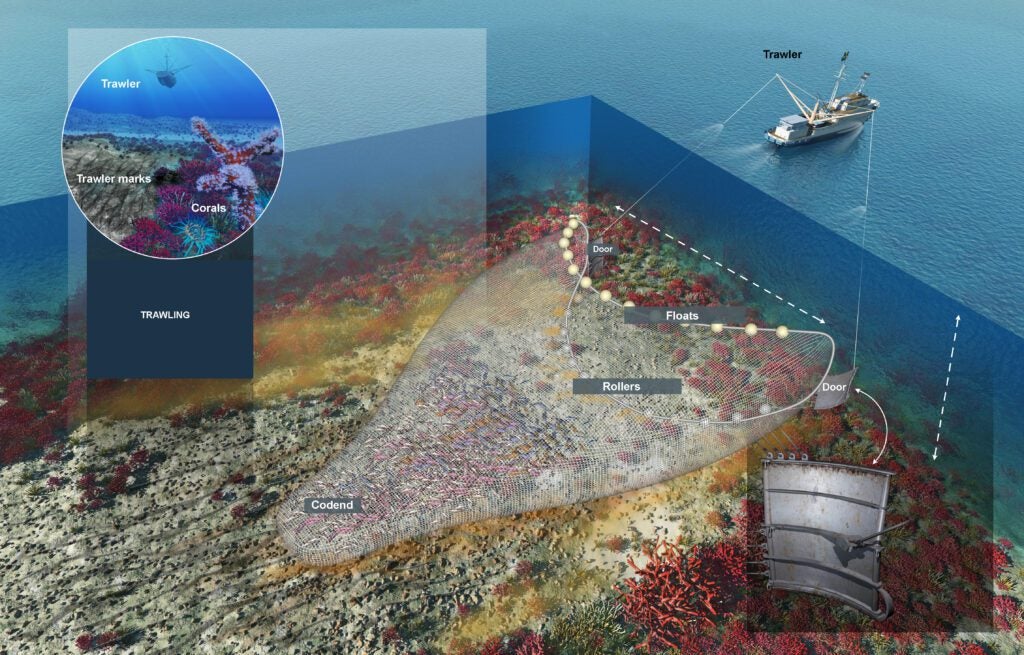

This productivity, however, is under threat. Using Global Fishing Watch satellite data from 2021, Oceana discovered that the Wadden Sea MPA in German waters endured an estimated 22,000 hours of apparent bottom trawling, a fishing method that can destroy seabeds and kill vulnerable wildlife while dragging weighted nets across the ocean floor. The previous year, this MPA was one the most heavily bottom-trawled of all of Europe’s protected waters.

The Wadden Sea is not an anomaly. A 2020 Oceana report titled Unmanaged = Unprotected: Europe’s Marine Paper Parks found that destructive fishing methods, including bottom trawling, occur in 86% of the area specifically designated to protect seabed habitats in European MPAs.

“Marine protected areas, as the name suggests, are supposed to afford protection to marine life,” said Vera Coelho, Oceana’s Senior Director of Advocacy in Europe. “Yet, bottom-trawling took place inside them. It is unacceptable that the EU continues condoning the destruction of the very places it has committed to protect.”

Studies show that MPAs promote ocean abundance when they are properly placed and managed. However, “paper parks” like the Wadden Sea fall short of this goal because they are protected on paper, but not in practice. To stop this worrying trend in ocean management, Oceana and its allies not only advocate for the creation of new MPAs in strategic locations, but also for stronger protections and meaningful enforcement in existing MPAs.

Oceana is actively campaigning to ban bottom-towed fishing gear, including bottom trawls and dredges, in every MPA in the EU. Oceana has also ramped up its presence in the United Kingdom, where campaigners are working to protect the MPA network — which covers over 30% of UK waters — from these destructive forms of fishing gear.

While there is much work to be done in Europe’s MPAs, Oceana’s habitat victories in the EU and around the world show that it is possible to enact and enforce strong protections for ocean ecosystems.

‘Placebo conservation’

Bottom trawling is detrimental to marine life. It can be compared to clear-cutting a forest because it bulldozes everything in its path, from sharks to stingrays to corals that can take centuries to regrow.

To date, Oceana and its allies have protected more than 10 million square kilometers (nearly 4 million square miles) of ocean habitat from threats such as bottom trawling. This includes banning bottom trawling in all of Belize’s waters, all of the Philippines’ municipal waters, all of the waters surrounding Chile’s seamounts, large pockets of U.S. and Canadian waters, and 4.9 million square kilometers (1.9 million square miles) of Northeast Atlantic waters at depths of 800 meters (more than 2,600 feet) and below.

Places that prioritize MPA enforcement often see biodiversity benefits. Analyzing the results from multiple MPA studies, Dr. Enric Sala and Dr. Sylvaine Giakoumi found fish biomass in marine reserves is on average 670% higher than in surrounding unprotected waters.

Another paper by Dr. Sala, co-authored by marine ecologist Dr. Boris Worm, an Oceana Science Advisor and associate professor at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada, found that fully protected MPAs can yield “triple benefits” for food security, biodiversity, and the climate.

MPAs can even be a boon to fishers. In effectively managed MPAs, experts say commercially valuable species that were once overexploited have the chance to recover. This can trigger a “spillover effect,” in which recovered species move beyond the boundaries of a no-take zone and enter areas where fishing is permitted. In other cases, MPAs forbid industrial fishing but allow sustainable, small-scale fishing to continue. This preserves access for artisanal fishers, who rely on those waters for their food and livelihoods.

Fishing techniques like bottom trawling can disturb carbon stored in the seafloor, and MPAs can provide a tool to help keep carbon locked in the seafloor that might otherwise be released by human activities.

The problem that Europe is facing is that none of these benefits will be realized if MPAs permit bottom-towed gear, Worm explained.

“Bottom trawling as an industrial, unselective, and disturbance-intensive fishery is, in many jurisdictions, not seen as compatible with protected area status,” Worm said. “If you call something a protected area, you shouldn’t be bottom trawling.”

In a previous study that Worm co-authored in 2018, researchers found the abundance of sharks, rays, and skates was reduced 69% in heavily trawled areas of the EU. These species are especially vulnerable to bottom trawls because many of them live near the seafloor and are too large to escape through the mesh of trawl nets.

However, Worm said the most surprising finding was that the average intensity of bottom trawling in MPAs across the EU was on average 1.4 times higher than in non-protected areas.

Herein lies the paradox: European countries are racing to meet conservation targets — including the global “30×30” goal of protecting 30% of the ocean by 2030, which some countries have already achieved — but without management measures, these MPAs are not necessarily better off. Oceana’s report determined the protections granted to many of these MPAs just barely meet the “legal minimum,” and only pertain to a limited number of features within each area rather than the ecosystem at large.

Worm said this practice is harmful because it creates an environment of complacency rather than true change.

“It creates a false sense of security that you’re doing something, and that’s dangerous because then you are not really addressing the problem,” Worm said. “It’s like if you’re sick and taking a placebo pill — you think it’s helping, but it’s not. I don’t think we should be satisfied with placebo conservation.”

That is why Oceana says its campaign to end destructive fishing in MPAs is so important.

Making progress

So why is the most destructive form of fishing allowed to occur in the most “protected” and productive parts of Europe’s ocean? Nicolas Fournier, Oceana’s Campaign Director for marine protection in Europe, explained that most of the MPAs in Europe do not include an outright ban on bottom trawling, or any activity for that matter.

An EU law requires impact assessments to be completed for activities that could undermine the conservation goals of an MPA, but those assessments are not routinely conducted for commercial fishing. In cases where assessments are done, bottom trawling is often only banned in smaller portions of an MPA — for instance, over particular reefs or seagrass meadows, but not in surrounding areas.

“We have examples of places where bottom trawling has been restricted in a very patchy manner,” Fournier said. “So you basically have dots on the map where you have small enclosures inside the MPA, but the broader MPA continues to be freely bottom trawlable.”

Another issue is that countries have up to six years to devise a management plan after designating an MPA, which enables political feet-dragging and affords industrial fishing interests the time to lobby against restrictions they find unfavorable, Fournier explained.

Fishing restrictions can also be easily blocked or delayed. The EU Common Fisheries Policy requires any proposed fishery closures in offshore MPAs — those located more than 12 nautical miles from shore — to receive the sign-off of every EU Member State that fishes in the area.

Despite these barriers, Oceana’s campaign to stop bottom trawling in MPAs across Europe is making progress. In May, The European Parliament adopted a non-binding amendment that called on the EU to prohibit “all extractive industrial activities” in MPAs. According to The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which sets international standards for MPA management, the definition of industrial fishing includes “all fishing using trawling gears that are dragged or towed across the seafloor or through the water column.” This type of industrial activity is not compatible with MPAs, according to the IUCN.

Fournier explained that even though the European Parliament did not mention bottom trawling by name, the language they adopted makes a compelling case for ending bottom trawling in MPAs across the EU.

“In our view, this definition is much more ambitious because it calls to prohibit all industrial destructive activities, which in our reading covers bottom trawling as well as other harmful fishing practices,” Fournier said. “If the EU wants to meet its ambitious biodiversity targets and be viewed as credible by the international community, it must ban bottom trawling in all MPAs immediately.”

This action by the European Parliament follows advocacy by Oceana and its allies. More than 170,000 people signed a petition to ban bottom trawling in MPAs, which was delivered to EU Commissioners at the end of 2021.

Progress is also being made in the UK, where bottom-towed fishing gear was used in 90% of offshore MPAs last year. Oceana recently secured a commitment from the government to manage bottom-towed fishing gear in its offshore MPAs by 2024. The UK is now taking steps toward this goal, having recently protected its largest sandbank, Dogger Bank, from bottom trawling. However, recent management proposals for 13 more MPAs indicate that the UK’s Marine Management Organisation will only protect certain features from bottom trawling, rather than the entirety of the MPAs.

A window of opportunity has also opened up in the EU, which introduced a Nature Restoration Law with legally-binding targets to restore degraded habitats on land and at sea. This law could

propel the EU to fulfill its [currently] non-binding goal of designating 10% of its waters as no-take zones by 2030.

Fournier said ambitions are high, but governing bodies may need an extra push to make real and lasting change — and that is where Oceana comes in.

“The EU is claiming to be a global leader in marine conservation, but in our own backyards, and in our own MPAs, bottom trawling continues,” Fournier said. “That’s what we’re fighting to change, so that gems like the Wadden Sea can be protected — for good.”