May 11, 2022

The plastic to pollutant pipeline

BY: Emily Nuñez

Most single-use plastics are made from fossil fuels, so why aren’t they part of climate change conversations?

Take a moment to consider the origins of a plastic bottle. What comes to mind? Maybe it’s a mental image of water bottles stacked on shelves at your local supermarket. Maybe it’s a factory that manufactures small plastic “nurdles,” or a plant that melts and molds those pellets into beverage bottles, yogurt cups, and clamshell containers.

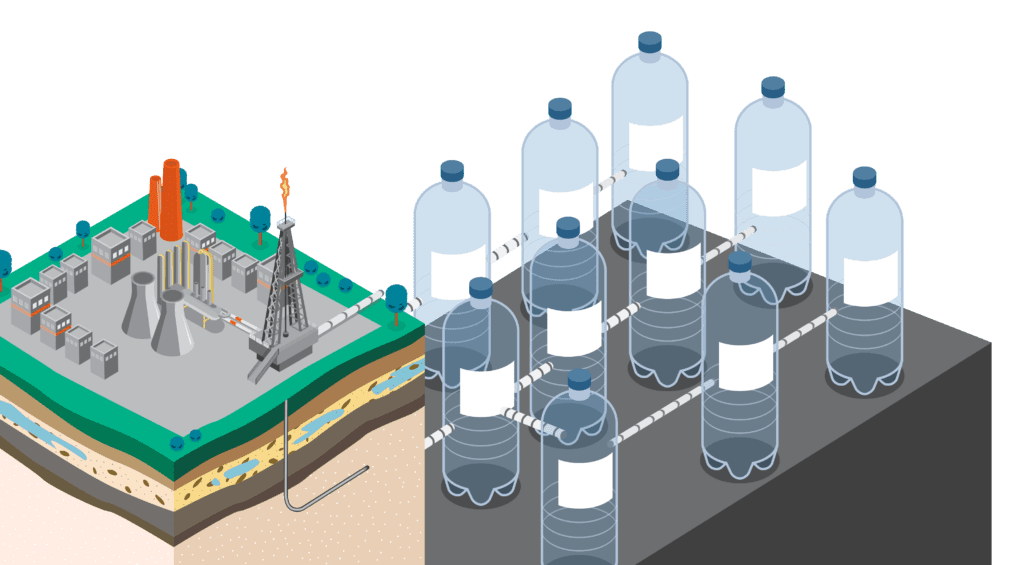

If you trace the process back far enough, you might arrive at a plot of land, perhaps in rural Pennsylvania, Colorado, or Texas. A mile or two below the surface is where you’ll find natural gas, which contains one of the main building blocks of plastics produced in the United States: ethane.

Advancements in technology have given drilling companies access to previously unreachable gas, fueling the fracking boom across America. In other countries, oil is still a primary feedstock for plastics. However, with global demand for fossil fuels expected to drop as countries shift to greener energies, drillers are increasingly turning to plastics for continued growth.

The plastics industry expects its 11 annual production will more than triple by 2050. Oceana asserts that this will take a heavy toll on our oceans, which are already inundated with plastic and suffering the effects of global warming and acidification. Greenhouse gas emissions are associated with the entire life cycle of a plastic object, from the extraction of fossil fuels to the incineration of unrecyclable plastic trash.

In fact, the plastic industry’s carbon footprint has doubled since 1995, according to a recent study led by Livia Cabernard from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. In 2015, plastics were responsible for 4.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

“To put this in context, if plastics were a country, it would be the fifth largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world,” said Christy Leavitt, Oceana’s plastics campaign director in the United States. “Climate change and plastic pollution are intrinsically linked, making it impossible to fight one problem without considering the other.”

Oceana’s global plastic campaigns are focused on implementing changes that slow the production — and pollution — of plastics. Reducing single-use plastics is one step governments and private industry can and must take to confront climate change.

‘The new coal’

The production of single-use plastics in the U.S. depends in large part on the fracturing of rock formations that are hundreds of millions of years old, the extraction of fossil fuels that are rapidly driving climate change, and the pollution of fenceline communities. In the end, consumers get products that are used for just a few fleeting moments, then thrown away.

For these plastics to get from the ground to grocery stores, millions of gallons of water and a cocktail of chemicals — some of which have been found to be toxic — are injected into the ground to “frack,” or hydraulically fracture, a single well. The pressure causes the shale to shatter, allowing gas to escape and flow up to the surface. It’s effective, but with a catch: The process is notorious for leaking methane, a potent planet-warming gas, into the atmosphere.

And fracking is just the first step. Natural gas has to be processed into separate components, including ethane and methane. Next, at sites called cracker plants, ethane molecules are exposed to extreme heat until they “crack,” or separate, into a highly flammable and hazardous gas called ethylene. That gas can then be processed into a resin, such as polyethylene, and turned into plastic products. Emissions are released during all of these steps — not to mention the carbon footprint associated with offshoring parts of this process to other countries.

In the U.S. alone, the plastic industry’s carbon footprint is expected to exceed that of coal-fired power plants by 2030, according to The New Coal: Plastics & Climate Change, a report published by Beyond Plastics, a research project at Bennington College in Vermont.

Though the links between plastic production and the climate crisis are glaring, international conferences on climate solutions seldom mention policies to curb single-use plastics. Much like ocean issues, plastic production is easy to ignore because, for most people, it is out of sight and out of mind.

Alexis Goldsmith, the national organizing director of Beyond Plastics, said their report shows that more than 90% of the emissions associated with plastics in the U.S. are released into just 18 communities. The people living in these communities are 67% more likely to be people of color, and they earn 28% less than the average U.S. household.

“The actual production of plastic is happening in a very small number of places, which makes it easy for the general population to be unaware of what it looks like to produce plastic,” Goldsmith said. “However, for those 18 communities, plastic production facilities and ethane crackers are located right on top of them.”

Places like these are sometimes called “sacrifice zones,” highlighting the systemic practice of placing polluting industries in areas where marginalized groups have been living for decades or centuries. Goldsmith said one example is a proposal from a subsidiary of Formosa, a Taiwanese company, to build one of the world’s largest plastic facilities in St. James Parish, Louisiana, which is home to historically Black communities.

St. James Parish is part of a longer strip of land along the Mississippi River that has been called “Cancer Alley” for its high number of oil refineries, chemical facilities, and plastic plants. Last year, human rights experts with the United Nations said Formosa’s plant, if built, would more than double the cancer risk that residents of St. James Parish face. They also expressed concerns that this facility could destroy at least four ancestral burial grounds of enslaved peoples.

“The African-American descendants of the enslaved people who once worked the land are today the primary victims of deadly environmental pollution that these petrochemical plants in their neighborhoods have caused,” the UN experts said in a statement, which urged the U.S. government to deliver environmental justice across the country, beginning with St. James Parish.

Globally, there is strong evidence that climate change — caused by plastics and other polluting industries — has the largest impact on the people least responsible for the crisis we are currently facing. According to Oxfam, people living in lower-income countries are more than four times as likely to be displaced by extreme weather than people in wealthy countries like the United States.

“Everyone should have breathable air, drinkable water, and clean oceans,” Leavitt said. “If we want to work toward that kind of future, tackling single-use plastics is a crucial place to start.”

The way forward

So how do we get there? Oceana’s plastic campaigns are focused on two complementary strategies: persuading global brands to choose plastic-free alternatives and urging governments to pass laws that ban or reduce wasteful plastics.

Past victories have shown that change is possible. In 2020, the government of Belize passed a law to eliminate single-use plastics from the food sector by the end of 2021. That deadline was postponed due to the pandemic, but Oceana continued to campaign for its effective implementation. In February, the Department of Environment announced that the sale of prohibited plastics would be phased out by Feb. 28, and a ban on the possession of prohibited items would be enforced starting March 31.

Peru also passed a law — largely developed by Oceana — that bans plastic bags and restricts other single-use plastics. The strongest anti-plastic pollution law, however, was passed by the Chilean government last year. Parts of it are now in effect, and once it is fully realized, it will all but eliminate single-use plastics from the food and beverage sector and bring refillable beverage bottles back to supermarkets and stores for the first time in decades.

Oceana won a big brand partner in Brazil last year when iFood, a major food delivery service, agreed to drastically reduce the amount of single-use plastic it gives customers. It’s the largest company of its kind in Brazil, and with Uber announcing it will be pulling out of the country, iFood’s market share is expected to increase.

Another component of Oceana’s strategy is calling on companies to increase the share of products they sell in refillable bottles, which can be returned, cleaned, and resold up to 50 times, depending on the material. In a major milestone, Coca-Cola recently announced it will make 25% of its worldwide packaging reusable by 2030. This commitment follows campaigning by Oceana, which found that just a 10% increase in the market share of refillable bottles sold in coastal countries could take 7.6 billion plastic bottles out of the oceans each year.

Looking ahead at what’s to come, Oceana continues to campaign for Amazon to reduce its single-use plastic packaging. In a report released in December, Oceana analyzed e-commerce packaging data and found that Amazon generated 599 million pounds (271,700 metric tons) of plastic packaging waste in 2020. This is a 29% increase over Oceana’s 2019 estimate of 465 million pounds (210,920 metric tons).

On the political front, there has been progress. Canada’s government recently shared a first draft of regulations that would ban several types of single-use plastic. Oceana’s team in the Philippines is also petitioning the government to include single-use plastics on a list of non-environmentally acceptable materials, which would essentially ban wasteful plastics.

In the United States, Oceana is ramping up outreach ahead of a ballot initiative that Californians will vote on this November. If successful, it would require plastic producers to reduce single-use plastic packaging and foodware by at least 25% over the next eight years. It would also prohibit plastic foam food containers and place a fee on single-use plastic packaging and foodware while requiring them to be reusable, recyclable, or compostable by 2030.

Oceana is also petitioning the National Park Service to stop the sale and distribution of unnecessary single-use plastics within national parks. A poll commissioned by Oceana found that 82% of American voters would support this decision, with 76% agreeing that single-use plastic items have no place in national parks.

Finally, Oceana and its allies are rallying support for the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act, which now has 124 cosponsors in the House and 15 cosponsors in the Senate. If passed, the act would phase out problematic plastics and put the onus on producers — not municipalities and ordinary citizens — to manage their waste. It would also prevent the widespread shipping of unwanted plastic trash to developing countries.

“We won’t eliminate single-use plastic overnight,” Leavitt said, “but policy change by policy change, we can start reducing its presence in our day-to-day lives and help ensure a better future for people and for the oceans.

This story appears in the Climate Issue (Spring 2022) of Oceana Magazine. Read it online here.