August 26, 2016

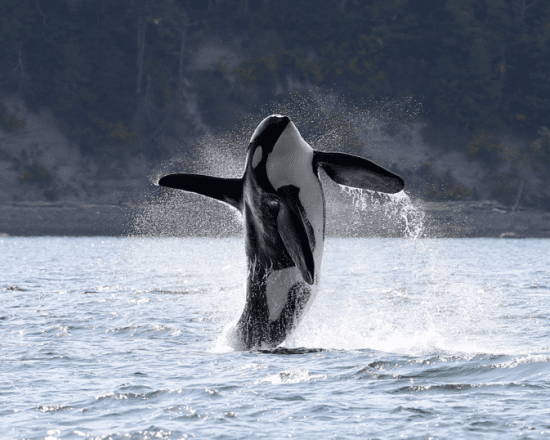

As Crisis Nears for Orcas and Salmon, Activists Urge the Removal of 4 Costly Dams

BY: Allison Guy

Dams need to come down, scientists say, to help bring back the salmon that endangered Southern Resident killer whales need to survive. But dam removal raises tricky questions of how to recoup lost hydroelectricity, irrigation and cash. For a string of four federal dams on the Snake River, however, these questions might be moot. The lower Snake dams degrade over a hundred miles of prime salmon habitat, cost taxpayers more money than they generate, and would be a relative bargain to breach.

Now, after decades of petitions and studies, the dams are still standing and the Snake’s salmon runs remain in bad shape. With only 83 Southern Residents left, whale advocates warn that it might be now or never for the Salish Sea’s most famous denizens.

The dams that almost weren’t

The way James Waddell tells it, the lower Snake dams should never have been built. Waddell is a former member of the Army Corps of Engineers who now fights for dam removal.

The four dams — Ice Harbor, Lower Monumental, Little Goose and Lower Granite — have a checkered history. In the 1920s, under pressure from business interests in Lewiston, Idaho to create barge-navigable routes on the Snake, the Army Corps of Engineers studied the feasibility of building dams — and rejected them as economically unviable. Dams were rejected again in the 1930s and the early 1940s.

Finally, Waddell said, the Corps “got clever” with a forth study in 1947, which showed a net benefit from navigation combined with hydroelectricity. It took another 15 years for money from Congress to show up, Waddell added, because East Coast politicians were skeptical of the dams’ value. Construction on the first dam began in 1962. The fourth and final dam, Lower Granite, was opened in 1975.

Endangered and expensive

The four dams on the lower Snake throw up big roadblocks for migrating salmon along a 225-kilometer (140-mile) stretch. This salmon superhighway was once prime spawning ground for spring and summer Chinook — goliaths of the fish world that beckon Southern Residents to the mouth of the Colombia every year. But this nursery is now a cemetery. The reservoirs behind the dams flooded big swaths of the river with murky, over-warm and predator-filled water.

These dams — along with an impassable dam in Hells Canyon and four other dams on the Columbia River — helped to send Chinook into a free-fall. In 1992, all runs of Snake River Chinook were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.

The Army Corps of Engineers and the Bonneville Power Administration have since spent over a billion dollars on hatchery programs, fish ladders and other efforts to boost salmon survival. These initiatives are so costly, Waddell said, that for every dollar spent on the dams taxpayers see only 15 cents in return. And despite more than 20 years of work, not a single Snake River salmon run — Chinook, sockeye or steelhead — has recovered.

“Removing these four dams may be the single biggest action that the U.S. can take to increase salmon abundance in the region,” said Ben Enticknap, Oceana’s Pacific campaign manager and senior scientist.

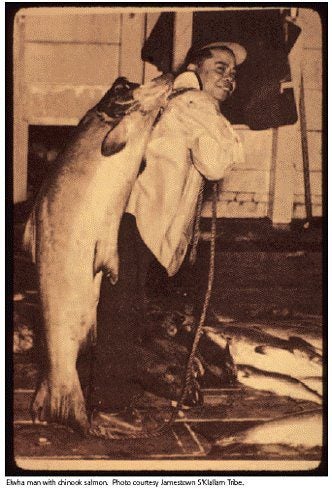

The Elwha example

Many sources cited the Elwha Dam as proof that salmon come quickly on the heels of dam removal. The Elwha, the largest dam removal project in the US, restored 70 miles of spawning habitat when demolition was completed in 2012.

Though the Elwha isn’t entirely comparable to the Snake dams — the Elwha was impassable, for example, and there are no longer other dams on the river — but it does offer hope. Soon after the Elwha River flowed freely once more, officials tallied 4,000 spawning Chinook upstream of the dam’s old site. More fish are expected to return this year.

“Salmon biologists were floored,” said Deborah Giles, the research director of the Center for Whale Research. “The Elwha Dam removal is a good example of how fast ecosystems can recover if we make the right decisions.”

A breachable moment

Even as evidence piles up, the Bonneville Power Company and the Army Corps of Engineers have remained immune to arguments in favor of breaching the dams.

In response the Snake River’s salmon landing on the Endangered Species List in 1992, the Army Corps of Engineers undertook a multi-year, $33 million effort to study salmon restoration options. Waddell explained that although breaching emerged as the winning choice, “the Corps ignored what their own data was saying on the economics. They overestimated the cost of breaching the dams by 300 percent.”

A decade later, a 2002 Corps-authored environmental impact statement admitted that improvements to fish passage systems around the dams were “unlikely to recover listed Snake River stocks.” Dam breaching, the statement said, “provides the highest probability” of recovering salmon stocks. Around the same time, a report prepared for the United States Fish and Wildlife Service concluded that “all available science” pointed to dam breach as the best way to bring back Snake River salmon.

Last May, a federal judge urged federal agencies to consider all possible options to restore the Snake’s salmon, including breaching the dams. This was the fifth time a federal judge issued a similar recommendation. “These efforts have already cost billions of dollars,” the judge noted in his ruling, “yet they are failing.”

According to one estimate, removing the lower Snake River dams could bring $4 to $20 for every dollar spent, mostly from boosting salmon for recreational, commercial and tribal fishers — not to mention fish-eating whales.

While these four dams provide about 2.9 percent of the region’s electricity, the Pacific Northwest’s power grid is currently overbuilt. “Any loss in energy production by removing these dams can be offset by investments in energy efficiency and truly salmon-safe wind and solar,” Enticknap said.

Advocates warn that the Southern Resident orcas can’t afford to wait much longer while humans debate. “We can’t lose any more key individuals,” Giles said, “or the genetics are going to get too small for the population to remain viable.”

The same may be true for salmon. “We are in a crisis situation now,” Waddell said. “Biologists have been telling us for decades that if we don’t breach the dams, we’re going to lose the genetics of our wild salmon. We are at a point now, biologically, where we cannot wait.”

Oceana is part of the Orca Salmon Alliance, a coalition of 10 environmental groups that addresses threats to orcas and Chinook salmon. Learn more here.

Previousy in this series: How a lack of salmon leads to an orca population slipping toward extinction, and why salmon have waned.