August 22, 2016

Dams Are Wiping Out Chinook Salmon — And Decimating Killer Whales

BY: Allison Guy

Perhaps nothing binds the land to the sea as deeply as salmon.

In the ocean-going phase of their lives, salmon along the west coast the United States and Canada feed sea lions, sharks, humans and an endangered family of killer whales. In rivers and streams, they nourish bears, birds — and forests. Up to 80 percent of the nitrogen in riverside trees can be traced to nutrients that salmon carried in their bodies from the ocean.

All salmon are a nutritional bonanza for their predators, but Chinook are the Mega Millions jackpot. These hulking fish — weighing an average of 40 pounds at maturity, but occasionally getting twice as big — are central to the existence of the endangered Southern Resident killer whales. Without Chinook, these orcas would starve.

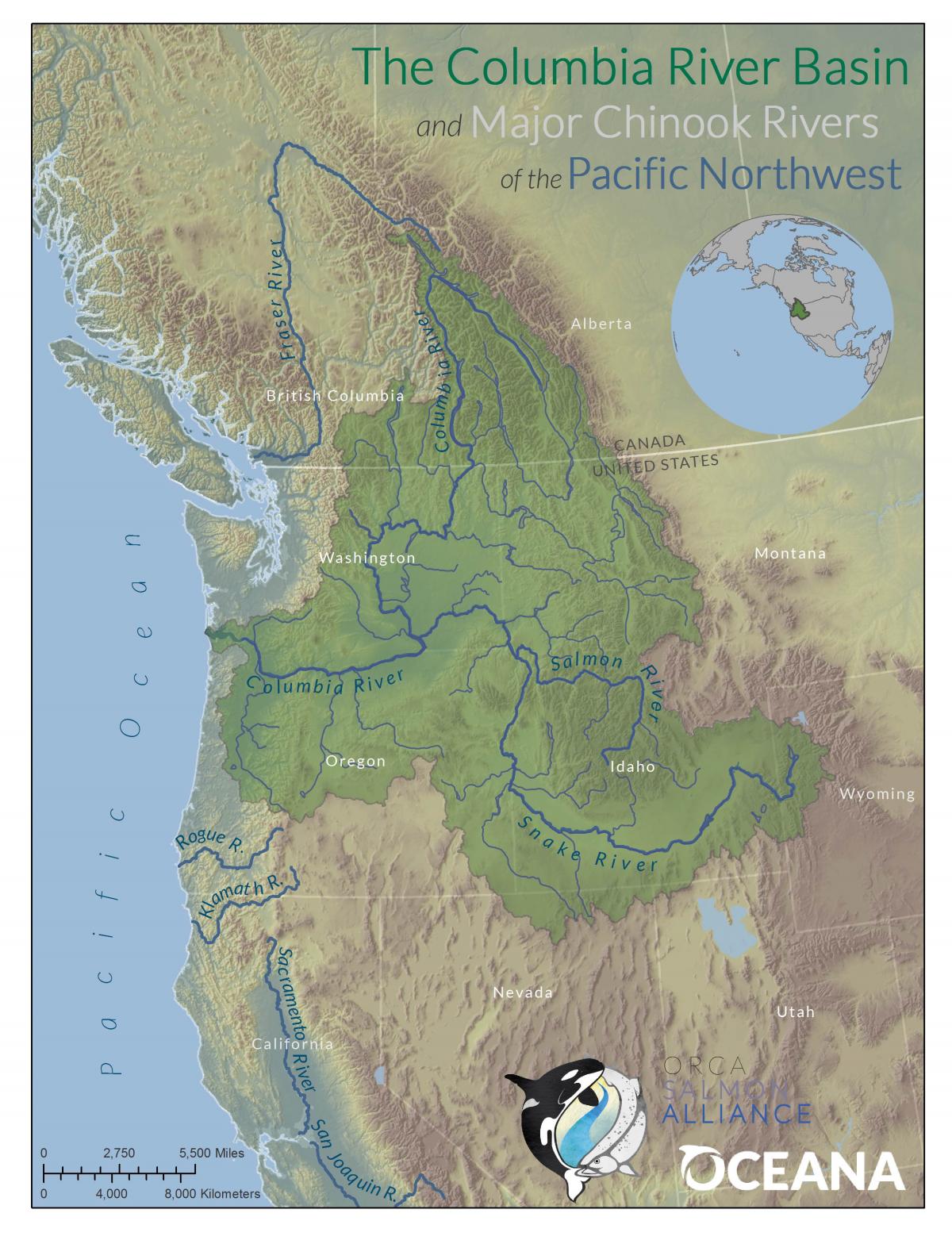

But in the Columbia River Basin, dozens of dams have severed salmon’s ancient routes to and from their spawning grounds. As the Chinook disappear, the Southern Residents are dying. If we want more orcas, whale advocates argue, we need fewer dams.

A river used to run through it

The 668,000 square kilometer (258,000 square mile) basin that drains into the Columbia River is a world-class fish factory. A vast latticework of tributaries creates thousands of kilometers of ideal salmon spawning grounds: clear, cool water, constant flow, and gravel bottoms that protect eggs and fingerling fish.

But dams have taken huge chunks of the Northwest’s salmon factory permanently offline.

The impassable Chief Joseph Dam on the Columbia, for instance, blocks salmon from 1,770 kilometers (1,100 miles) of spawning grounds. The Hells Canyon Dam on the Snake River, a tributary of the Columbia, shut down 480 kilometers (300 miles) of prime salmon habitat.

The Snake is the Columbia River’s biggest tributary. Historically, it produced more salmon than any other branch of the Columbia. An 1895 entry in a local’s journal noted that the fish were so thick in the Snake he had to shoo them away before his spooked horse would cross.

But Chinook have been in “rough shape” since the 1970s, said Bert Bowler, a former Idaho Fish and Game biologist who is now an independent advocate for restoring salmon habitat.

Since then, little has changed. “Almost all runs of wild Chinook salmon within the Southern Residents’ range — I would venture to say all Chinook runs — are decimated,” said Deborah Giles, the research director of the Center for Whale Research.

The king of salmon

The spring and summer-spawning Chinook that mate in Idaho’s remote Salmon River are titanic fish. They need giant reserves of fat to fuel a grueling 1,100 kilometer (700 mile) swim up 2,000 meters (6,500 feet) of elevation gain. “No other population in the world migrates that distance and that elevation,” said Bert Bowler.

Tens of thousands of Chinook plough their way up the Columbia River, hang a right at the Snake River and a final left at the Salmon. Some of these fish will end their journey in the Salmon River’s Middle Fork. The Middle Fork runs through Idaho’s Frank Church Wilderness — the largest contiguous wilderness area in the lower 48. There, the exhausted Chinook throw a last-chance reproductive party and then die. Their eggs hatch, and in a year or so the next generation follows the current downstream to the sea.

At least, that’s how the story should go.

The Salmon once produced 40 to 45 percent of the Columbia Basin’s spring and summer Chinook. But in recent years, only around 1.1 percent of the Chinook that hatch in the Salmon have returned to their home turf to spawn as adults.

The once-great Snake

In two big ways, Middle Fork Chinook are lucky fish. First, the Middle Fork is pristine, high-altitude habitat. Fed by snowmelt, this river is relatively insulated from the salmon-killing heat that’s becoming more common due to climate change. And second, the Salmon is one of the longest undammed rivers in the US.

But in its seaward migration, a young Middle Fork salmon’s lucky streak ends once it hits the Snake. In Washington State, four dams on the lower Snake River stand between the fish and the sea. The Snake then runs into the Columbia, where four more big dams await.

Though these dams have fish ladders and other bypass systems, that doesn’t make them safe for salmon. Depending on environmental conditions, these dams may claim 50 percent of Chinook smolts as they migrate to the sea.

The reservoirs behind the dams are graveyards. The water can be so slow-moving that salmon smolts can’t use the current to orientate themselves, and they get lost and die. The deep water hosts predators like pike and bass that feast on young salmon. Many fish cannot find safe passage around the dam, and instead take a perilous trip through the hydroelectric turbines.

Warmed by the sun and agricultural runoff, the stagnant reservoir water can go above 21 C (70 F). These temperatures are fatal to smolt. Adult salmon stop migrating and seek shelter in cooler waters. If the heat forces them to wait too long, they can run out of energy reserves or fall prey to disease. In 2015, hot water killed off half of the Columbia’s sockeye salmon run, around 250,000 fish.

“We’re finding whole populations, hundreds of thousands of fish, that are being lost in the river because it’s too hot,” Giles said. “It’s a wonder of nature that any salmon make it.”

Up next: How breaching the four lower Snake River dams could save Southern Resident killer whales, Chinook — and money. Previously: How a lack of salmon leads to an orca population slipping toward extinction.