June 17, 2022

The WTO agreement saves face, but does it save fish?

BY: Daniel Skerritt

By Daniel Skerritt, Senior Analyst at Oceana

After a frustrating drawn-out week at the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) 12th Ministerial Conference (MC12) in Geneva, Switzerland, member country officials have finally concluded talks and reached consensus on an agreement to reduce fisheries subsidies.

At least, that was the stated intention and the principal goal behind these negotiations.

WTO members have been debating the best way to control fisheries subsidies since the group convened in Doha, Qatar, in 2001. An agreement appeared to be in sight in 2008, only to falter. Then, in 2015, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) reinvigorated efforts by explicitly calling for the WTO to prohibit harmful fisheries subsidies – which facilitate overcapacity, overfishing, and even illegal fishing.

The agreement made this week, however, falls short of the target. It does not include a single reference to capacity-enhancing or harmful fisheries subsidies in the main body of the text, let alone measures that would reduce their provision. What could have been a watershed moment for international fisheries governance and the state of the ocean itself is yet another missed opportunity.

The meager fisheries subsidies agreement highlights the difficulties in delivering meaningful collective action to solve shared problems. This is the first new WTO agreement in almost a decade! This ultimately calls in to question whether the WTO is the most suitable forum for addressing global environmental issues, especially given increasing geopolitical turmoil and the growing tendency for countries to protect short-term self-interests over sustainability and equity.

Where does the agreement fall short?

First, we should note the few positives of this outcome. The WTO has reached consensus on a new agreement for the first time in almost a decade. It requires countries to provide data on their subsidies, in combination with the fleets and fish stocks that those subsidies impact. It calls on member countries to stop funding illegal fishing and fishing on overfished stocks. It is a global multilateral set of rules on fisheries subsidies. However, it is not the first set of multilateral rules – regional agreements, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), and the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) already have provisions against harmful fisheries subsidies.

This is where most of the positive news ends, at least for now.

The agreement’s two major articles, which target illegal fishing and fishing on overfished stocks (though with exemptions), will likely remove a trivial share of global harmful subsidies at best. The measures’ implementation will rely heavily on self-reporting from the subsidizing country themselves. If country-level honesty and integrity was the solution to removing harmful fisheries subsidies, did we really require 20 years of negotiation to get here?

The second, more fundamental issue, is that these measures discipline illegal fishing and overfishing, not harmful subsidies. The primary objective of these negotiations was to discipline harmful subsidies. This has seemingly been lost during the political mastications of MC12.

The removal of measures that explicitly relate to the harm that subsidies themselves cause takes much of the impact out of this agreement. It was important that member countries recognized and accepted that it is the provision of subsidies in and of themselves can alter the economics of a fishery and can cause harm to fish stocks. Although the text includes a promise to revisit these measures in the future, history suggests that we should not set our hopes too high for significant future advances.

Why is a meaningful deal on fisheries subsidies so important?

The timing of this setback is crucial. Our fisheries are in poor condition. FAO data indicate that about 35% of global fisheries stocks are overexploited and in need of rebuilding; another 57% are fully exploited and have no room for additional capacity (FAO 2022).

Yet the world’s governments continue to finance overcapacity and overfishing. They do this by lowering the costs of fishing. This in turn incentivizes investment in additional fishing effort.

This financial leg-up allows fishing vessels to continue to operate despite dwindling fish stocks and diminishing returns. Fishing continues beyond the point that would otherwise be unprofitable or unsustainable. This artificially incentivizes the expansion and maintenance of huge fishing fleets, starkly juxtaposed against the availability of fish. This heightened risk of overfishing reduces our ability to manage fisheries sustainably.

Other factors certainly contribute to the dire state of fisheries— ineffective management, habitat loss, illegal fishing, and climate change — but eliminating harmful fisheries subsidies would have been the single greatest action we could have taken to help reverse the situation. It was also relatively straight-forward, at least technically, but evidently not politically.

At a time when the world’s nations should be pulling back from this destructive practice, they are instead providing billions of dollars of taxpayers’ money to fund excessive fishing — this weak WTO agreement means this is unlikely to change any time soon.

How are harmful fisheries subsidies spent?

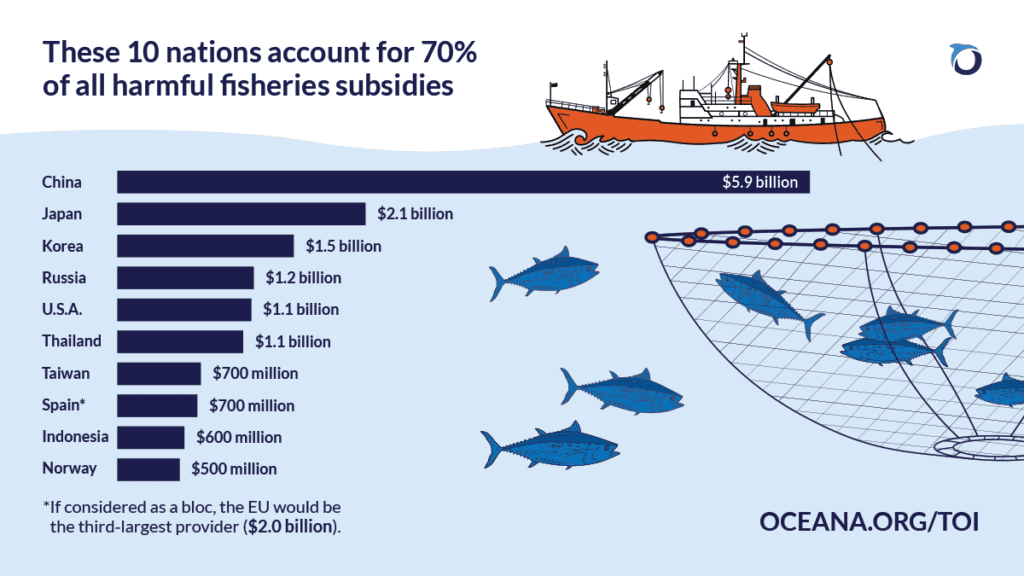

Harmful fisheries subsidies are no paltry sum. In 2018, around $22 billion was spent on supporting excessive fishing. In fact, since the WTO began their negotiations in 2001, more than $400 billion USD has been squandered on subsidies that promote overfishing.

But harmful fisheries subsidies don’t only harm fish, they also harm the hundreds of millions of people who rely on fish for food and employment. As articulated by Oceana’s Senior Director of Global Policy, Philip Chou:

“Strict rules on fisheries subsidies are critical for achieving sustainable and equitable oceans. Harmful subsidies encourage overfishing and exacerbate inequities between rich and poor nations, small and large-scale fishers. Failure to reach a meaningful agreement means the harm they cause will continue.”

The majority of harmful subsidies are provided by the world’s richest countries. They disproportionately support their large-scale and distant-water fishing fleets, usually by reducing the cost of fossil fuels. Subsidizing distant-water vessels means that the negative impact of these funds is not confined to the waters of the subsidizing nations.

How do harmful fisheries subsidies affect others?

A recent Oceana study revealed that in 2018 the world’s top-10 subsidizing countries spent more than $5 billion on fishing in the waters of other countries, including several developing countries that are heavily reliant on fish for food and livelihood security.

A second Oceana supported study revealed China’s subsidizing behavior. The report reveals that China’s subsidies increasingly flow to their distant-water fishing vessels. The Chinese government stopped tracking fuel subsidies for distant-water fishing in 2016, shrouding the true extent of their subsidizing in secrecy.

Thanks to harmful subsidies distant-water fishing vessels are able to travel thousands of miles in pursuit of lucrative fishing opportunities. Unfortunately, this can often come at a cost to the ‘host’ nation.

In West Africa, for example, millions of people rely on fisheries for work and food. This region is also the destination of many subsidized foreign fishing vessels targeting tuna, sardinella, and other coveted fish.

Small pelagic species, like sardinella, are especially important to West Africans. In Senegal, for example, they account for about 80% of fish consumption. But they are increasingly being exported or used for non-food processing such as fishmeal. Reduced access for local people has led annual per capita consumption of small pelagic fish to reduce from 18 kg in 2009, to 9 kg in 2018.

Rich distant-water fishing nations are outspending most other nations when it comes to funding their fishing fleets. Oceana Board Member, Dr. Rashid Sumaila, explained that:

“The mismatch between the cost and benefits of fisheries subsidies has real moral and ethical implications. On average, twice the dollar amount of subsidies from foreign nations goes toward enabling distant-water vessels to fish in Africa than what Africa provides to its own domestic fisheries.”

A similar story is reflected domestically for almost every country. Large-scale, industrial fishing fleets benefit from approximately 80% of all fisheries subsidies. In fact, an individual fisher on large-scale vessel will benefit from three and a half times more harmful subsidies than a small-scale fisher. This imbalance is even more stark in certain countries. In Spain and India, for example, small-scale fishing fleets receive only about 2% and 10% of harmful fisheries subsidies, respectively.

This unequal support exacerbates the political and economic marginalization of small-scale fishers and coastal communities.

Having fair access to local fish would make the world of difference to the estimated 629 million vulnerable people around the world who are reliant on fish for food and important micronutrients.

The WTO fisheries subsidies agreement could have helped to rebalance access by withdrawing significant support to the inefficient industrial and distant-water fishing fleets and redirecting that money to support community-based projects that focus on fisheries management, conservation, social justice, and food security, particularly for vulnerable coastal communities and small-scale fishers.

What comes next?

It is not clear. While this agreement is a politically significant achievement, the feebleness of the contents may lead to increasingly vociferous arguments that the WTO is incapable of achieving meaningful fisheries subsidies reform—and right now that position is hard to argue with.

Time will tell whether the promises to continue to strengthen the agreement will come to fruition. In terms of having a substantive impact on fisheries subsidies, those amendments are necessary. We will continue to push for a stronger agreement, and if achieved, we will celebrate it.

Excuses that negotiations were complicated by geopolitical unrest are probably fair, but do not exonerate WTO members.

Perhaps strong plurilateral, regional, or bilateral subsidies agreements are attractive options. But these alternative routes may be blocked by the very existence of this WTO text. We now have a legally binding multilateral document on fisheries subsidies—albeit somewhat ineffective. Whether we can build from here and make further progress towards achieving the original aim is unclear at best.

The WTO have kicked the can of fisheries subsidies down the road for more than two decades. And while this agreement will be hailed by some as a win for fisheries and a boost to sustainability, I fear that all it will do is keep fisheries subsidies locked in perpetual WTO negotiations. All while our oceans will continue to be plundered and fish and fishers will continue to lose out.