September 16, 2021

Wild seafood has a lower carbon footprint than red meat, cheese, and chicken, according to latest data

BY: Emily Nuñez

What does it take to produce a rack of ribs, a double cheeseburger, or a side of mozzarella sticks? On an industrial scale, foods like these come with a tradeoff: Rising demand for dairy and red meat means fewer trees, less arable land, less fresh water, and more planet-warming gases released into the atmosphere. Our global food system is responsible for a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to the climate crisis we are currently experiencing.

Under business-as-usual scenarios, this problem will escalate. According to the United Nations (U.N.), there will be 2 billion more mouths to feed by 2050, and the world must produce 70% more food to meet this demand.

Feeding the world doesn’t have to take such a heavy toll on the environment, though. When incorporated into a balanced diet, wild seafood alleviates some of the demand for red meat and supplies a healthy source of protein and micronutrients. Marine fisheries currently play a role in food security and nutrition for more than 700 million people around the world, and a restored ocean could feed 1 billion people a seafood meal every day.

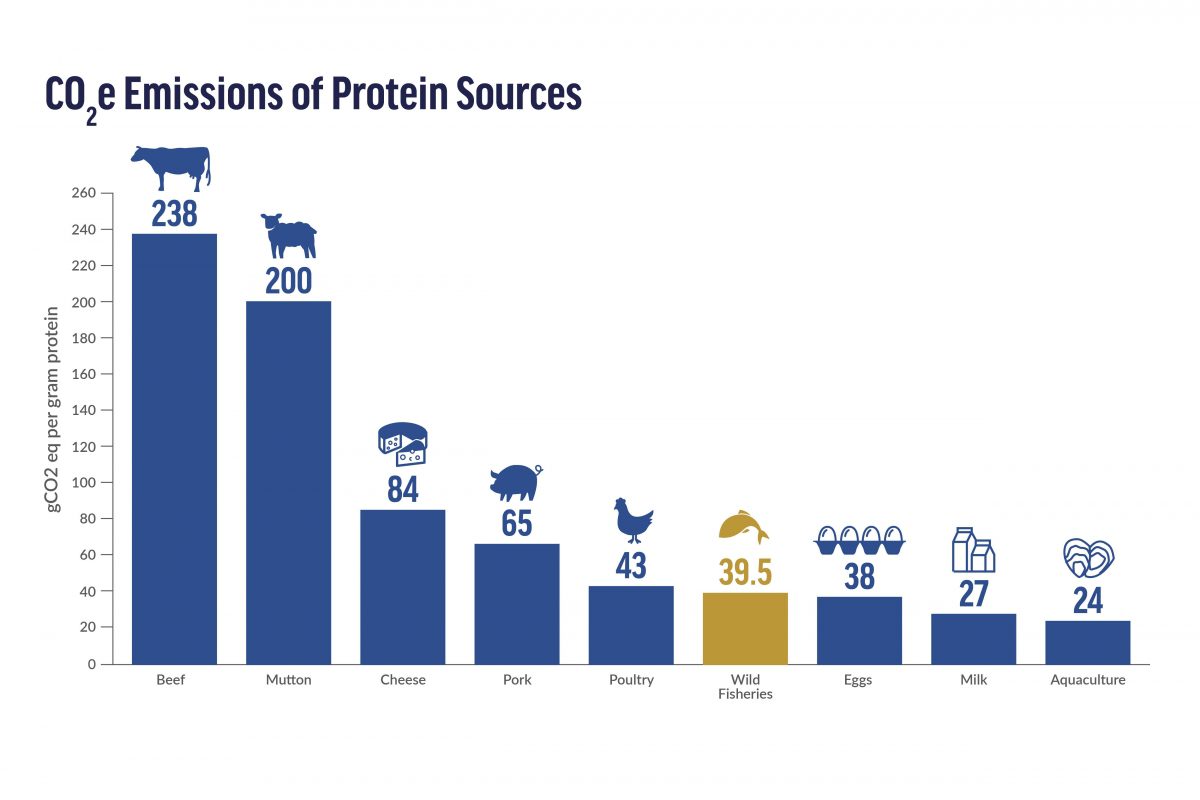

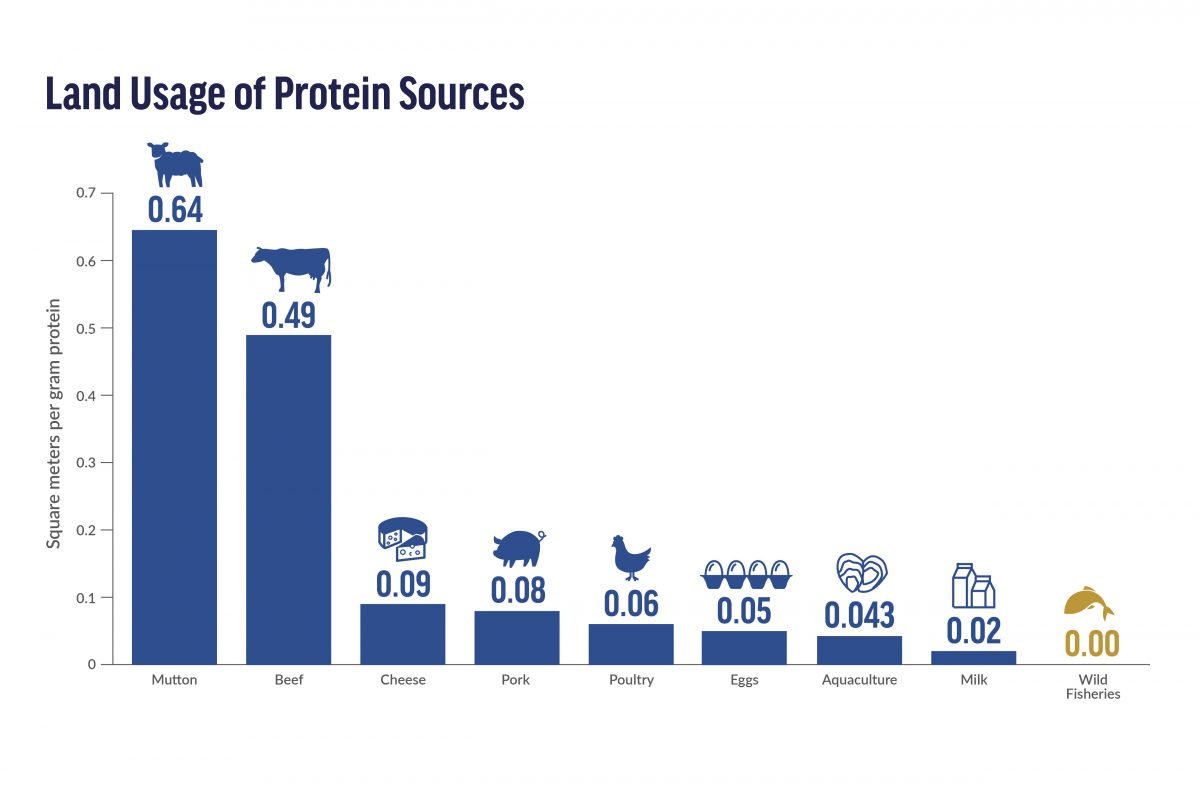

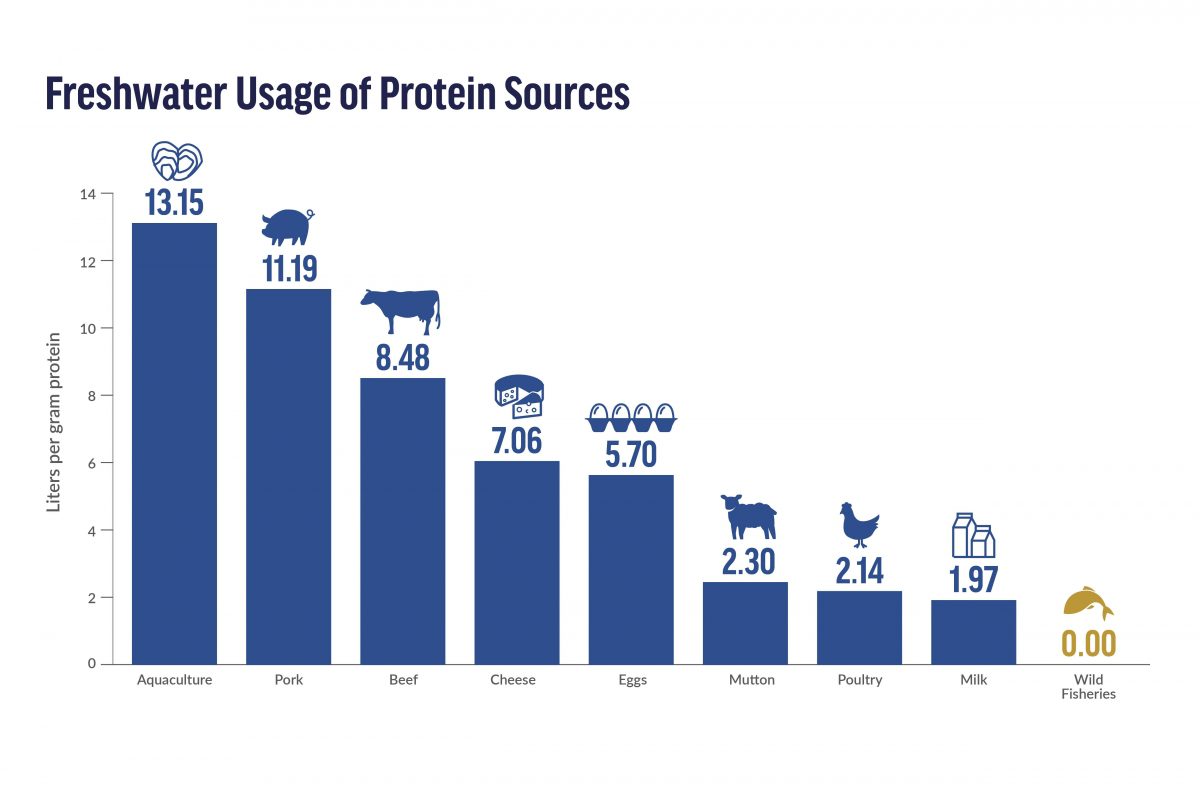

We have long known that wild fisheries have lower CO2 emissions than beef, mutton, cheese, pork, and poultry. Wild fisheries also require virtually no fresh water or land to harvest. This conclusion is once again supported by new research from Dr. Jessica Gephart, an Oceana Science Advisor and Assistant Professor of Environmental Science at American University.

Led by Gephart and supported by 17 other researchers around the world, this latest assessment of aquatic foods is the most comprehensive one to date. Researchers analyzed the greenhouse gas emissions, freshwater use, land use, and nitrogen and phosphorus emissions of 23 species groups accounting for more than 70% of the world’s “blue food” production, which refers to both aquaculture products (or farmed fish and shellfish) and capture products (or “wild” foods from the ocean and inland waters).

When you compare these findings to a world-renowned study on the environmental impact of other protein sources – conducted by Joseph Poore and Dr. Thomas Nemecek in 2018 – a full picture starts to emerge. Carbon emissions associated with wild seafood are six times lower than that of beef, five times lower than that of mutton, and more than two times lower than that of cheese.

Check out the graphs below to see how wild fisheries stack up against other foods in terms of their environmental impact.

Of the wild seafoods assessed, small pelagic fish (like anchovies and sardines) have the lowest CO2 emissions. For comparison, one hamburger has roughly the same carbon footprint as 9 pounds of wild sardines.

Of the wild seafoods assessed, small pelagic fish (like anchovies and sardines) have the lowest CO2 emissions. For comparison, one hamburger has roughly the same carbon footprint as 9 pounds of wild sardines.

Wild seafood’s carbon footprint is already considerably lower than red meats, and it might be even lower than this latest data reflects. That’s because people who catch marine and inland species to feed themselves and their families are largely unaccounted for in official data. These groups often use non-motorized vessels or no vessels at all – activities that “likely generate few emissions,” according to researchers.

While not factored into this study, CO2 emissions are also associated with the transport of seafood, which is one of the world’s most heavily traded food commodities. For these reasons, “little and local” is a good rule of thumb when selecting wild seafood on the basis of environmental impact.

Of course, no food is completely impact-free, and that includes wild fisheries. However, by enacting science-based policies that reduce bycatch, stop overfishing and destructive fishing (including bottom trawling, which is carbon-intensive), and prioritize the rebuilding of depleted fisheries, we can minimize harm and make eco-friendly blue foods more readily available, while simultaneously reducing the world’s reliance on red meats. For much of the global population, especially in coastal and tropical communities, seafood is a relatively accessible food source.

Aquatic foods could become even more affordable under a “high production scenario” in which capture fisheries are better managed and aquaculture innovation continues in the future. This finding comes from separate research led by Dr. Christopher Golden, an Oceana Science Advisor and Assistant Professor of Nutrition and Planetary Health at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. (Golden also co-authored the Gephart et al. paper, both of which were published yesterday in Nature as part of a Blue Food Assessment examining the role of aquatic foods in sustainable and equitable food systems.)

“Globally, we find that a high production scenario will decrease aquatic animal-source food prices by 26% and increase their consumption, thereby reducing the consumption of red and processed meats that can lead to diet-related non-communicable diseases, while also preventing approximately 166 million people from inadequate micronutrient intake,” Golden and co-authors wrote in their paper.

They note that aquatic foods “present myriad options for supplying nutrients” compared to the limited variety of land-based animal proteins that are available to most consumers. More than 2,370 wild seafood species are currently being harvested, and more than 620 species are being raised by aquaculture, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the U.N.

Many of these species are rich in vitamins, fatty acids, and minerals (such as calcium, iron, and zinc). According to Golden et al., “Our analysis indicates that the top seven categories of nutrient-rich animal-source foods are all aquatic foods, including pelagic fish, bivalves, and salmonids.”

Access to nutrient-packed fish could make an enormous difference in the diets of vulnerable populations. Hunger affects 690 million people around the world, and more than 2 billion people suffer from “hidden hunger,” or micronutrient deficiencies. Fisheries – when managed responsibly – can help fill those gaps in a healthy way.

Time and time again, history has shown that rebuilding plans in strategic places can bring fish back from the brink of collapse – often in just five to 10 years. In a separate study led by Michael Melnychuk, researchers found that fishery rebuilding plans “rapidly lowered fishing pressure towards target levels and emerged as the most important factor enabling overfished populations to recover.” Just 29 countries and the European Union are responsible for nearly 90% of the world’s fish catch, which means that success in these places will have a dramatic worldwide impact.

We shouldn’t have to choose between nourishing people or preserving our land, water, and air. By taking a country-by-country approach, we can protect biodiversity in our oceans, mitigate climate change, and feed populations who need it most. Click here to learn more about how saving the oceans can help feed the world.