March 11, 2021

COVID-19 shook the seafood sector. Researchers say it now gives us a chance to change the way we feed the world.

BY: Emily Nuñez

COVID-19 upended life as we know it, affecting how we work, who we interact with, and even what we eat. Much has been said about the pandemic’s effect on agriculture and livestock – including widespread fears of beef and pork shortages in the United States – but disruptions to seafood supply chains seldom make front-page news.

However, COVID-19 also changed how and when we eat seafood, according to new research analyzing the first five months of the pandemic, led by Dr. Dave Love from the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future. In high-income countries like the U.S., where seafood is often considered a “restaurant food,” business closures constrained markets for live and fresh seafood. Likewise, in the European Union, slow business at restaurants led to a 30% drop in prices for live and fresh seafood.

Low-income countries also saw a shift in eating habits – at a cost to human health. With household incomes plummeting during the pandemic, many people are less willing to spend their limited funds on nutrient-dense foods like fish. Instead, they may opt for less expensive “staple foods” like starches, which are filling but do not constitute a complete nor a balanced diet.

Yemen, a country heavily dependent on seafood, has been hit by war, climate change, and now COVID-19, leading to famine. Overall, global food insecurity has spiked, with 80-132 million new people experiencing hunger as a direct result of the pandemic, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Oceana’s “Save the Oceans, Feed the World” campaign is focused on restoring the oceans so that we can feed 1 billion people a healthy seafood meal every day. As part of that framework, Oceana is also identifying countries where improved fisheries management could yield more fish for local communities facing micronutrient deficiencies. Considering that COVID-19 disruptions to the seafood sector are likely to continue, elevating the risk of malnutrition and hunger around the world, this is an especially time-sensitive task.

More than a year after the emergence of COVID-19, it is imperative that we identify the parts of our global food system that do not serve everyone’s best interests, lead author Love said while presenting his team’s research during a virtual seminar.

“Returning to business as usual following the pandemic would be a missed opportunity to fix the parts of the food system and the seafood sector that were not working even before the pandemic, whether that’s environmental sustainability, nutrition security, or social equity,” Love said.

So how can we go about building a more resilient and equitable seafood sector? Love and co-authors offered a few suggestions:

1. Countries should diversify their food networks.

Many countries are increasingly importing seafood from a shrinking pool of exporters, while others are increasingly exporting their fish rather than selling it domestically. As COVID-19 has shown, doing so exposes both importers and exporters to risk.

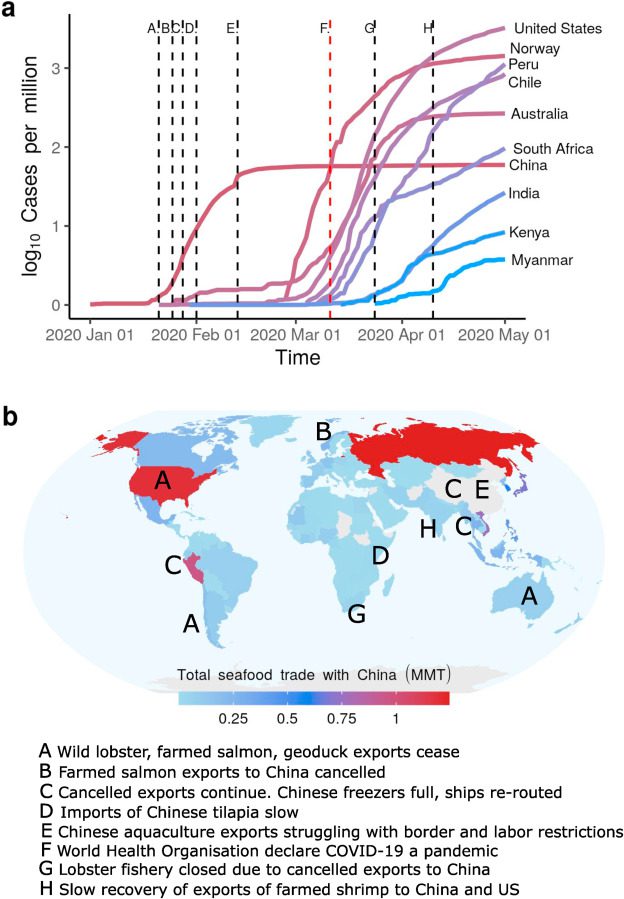

In January 2020, China stopped importing live animals to help contain the disease, but doing so brought South Africa’s lobster fishery to a screeching halt. According to the FAO, as much as 90% of South Africa’s rock lobster catch is exported to China.

Love and fellow researchers recommend that countries strengthen their local food systems and connections to a greater number of markets, enabling them to switch more freely between products or divert their products to other markets when disruptions occur.

Countries that were able to reroute their products to other markets were more resilient to the impacts of the pandemic. However, in doing so, some ended up exposing low-value markets in low-income food-deficit countries to trade shocks. As researchers wrote in their paper, “Efforts to build resilience following COVID-19 should consider resilience to what?, for whom?, and for what purpose?”

2. Policymakers should avoid short-term coping strategies that jeopardize ocean abundance.

If history is any guide, overfishing will be a heightened risk as countries attempt to reboot their economies in the wake of COVID-19. Surges in fishing activity occurred following World War II and, more recently, after the 2004 tsunami in Sri Lanka. Following the latter natural disaster, Sri Lanka’s government provided direct aid to fishers in the form of new fishing gear. Considering that 80% of the country’s fishing vessels and infrastructure were destroyed, there was a critical need for aid, but it also had the unintended consequence of causing increased fishing pressure.

“Unsurprisingly, [Sri Lanka] saw a spike in fish catch and then a drop after that,” said Dr. Jessica Gephart, an Oceana Science Advisor who co-authored this paper alongside Love, Oceana Science Advisor Dr. Eddie Allison, and others from scientific institutions around the world. “That’s an example where it might seem like you’re really helping a fisher, but you may have created a collective problem by overstimulating catch. Proper management could prevent that.”

Gephart said governments should take special care to ensure that their policies do not exacerbate other environmental stressors or jeopardize long-term sustainability. Given that the fishing sector has seen significant setbacks, governments could face political pressure to loosen regulations or allow more fishing to make up for losses.

3. We should use this ‘turning point’ to improve our food systems.

In their paper, Love and other authors backed a United Nations recommendation to reflect on what we want our food systems to look like going forward. The global agency wrote in a June 2020 policy brief that the COVID-19 pandemic “can serve as a turning point to rebalance and transform our food systems, making them more inclusive, sustainable, and resilient.”

To achieve this, Love et al. recommend that governments – and other parties within the seafood supply chain – switch from short-term to long-term planning. A preventative approach is necessary to protect countries from future shocks. It could also improve their resilience to ongoing stressors like climate change or political instability which, as we have seen around the world, can cause major disruptions to food supply.

They also recommend focusing future resilience-based research on the parts of the seafood system that serve the people most dependent on seafood for nutrition and jobs.

According to Gephart, stronger seafood traceability would also improve countries’ resilience to future “shocks” like COVID-19 because it would give them a clearer picture of where seafood is coming from, what species are being consumed and in what amount, and who would be most affected by disruptions to the supply chain.

Oceana’s position

Concerning the increased risk of overfishing following the pandemic, studies estimate that half of global fisheries are already overexploited, and another 40% are fully exploited with no room for additional fishing. Demanding more from our oceans to make up for losses may result in short-term gain, but doing so would only lead to long-term devastation.

As for inclusivity – or the lack thereof – nutrient-deficient people around the world are being deprived of the very fish extracted from their shores. In some cases, local fish are diverted to fishmeal factories that primarily feed carnivorous farmed fish and pigs in wealthier countries. In other cases, economic or physical barriers to access, international trade deals, or foreign fleets that plunder other countries’ waters are to blame.

Fisheries management should start to address more questions of access, according to Oceana Chief Scientist Dr. Katie Matthews. “For example, rebuilding a fishery that supports an offshore foreign fleet which sends all of its catch abroad and doesn’t improve the food security of nearby coastal communities is not going to be helpful,” Matthews said.

Secondly, a more sustainable seafood sector would prioritize science-based fisheries management, transparency at sea, and traceability throughout the supply chain, all of which Oceana campaigns for.

Sustainability also has a large climate component. According to the U.N.’s June 2020 policy brief, food systems are responsible for nearly a third of all greenhouse gas emissions. Notably, while not mentioned in the U.N. brief, many wild-caught seafoods have a lower carbon footprint than other animal proteins, and harvesting these foods requires virtually no fresh water or arable land. Our oceans are often described as victims of climate change, but they can also be part of the solution.

Going forward, as we mull over the many ways that our food system could benefit from transformative change, it is worth considering how those changes could create ripple effects that benefit the billions of people around the world reliant on seafood.